Updated 9 May 2020

Peter Lobner

1. Introduction to the Mile-High Skyscraper

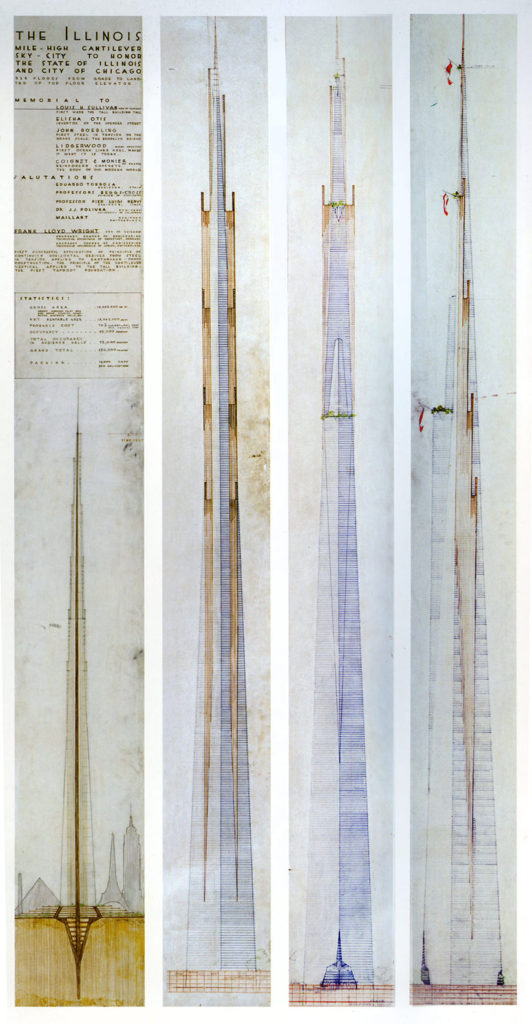

On 16 October 1956, architect Frank Lloyd Wright, then 89 years old, unveiled his design for the tallest skyscraper in the world, a remarkable mile-high tripod spire named “The Illinois,” proposed for a site in Chicago.

Source: Al Ravenna via Wikipedia

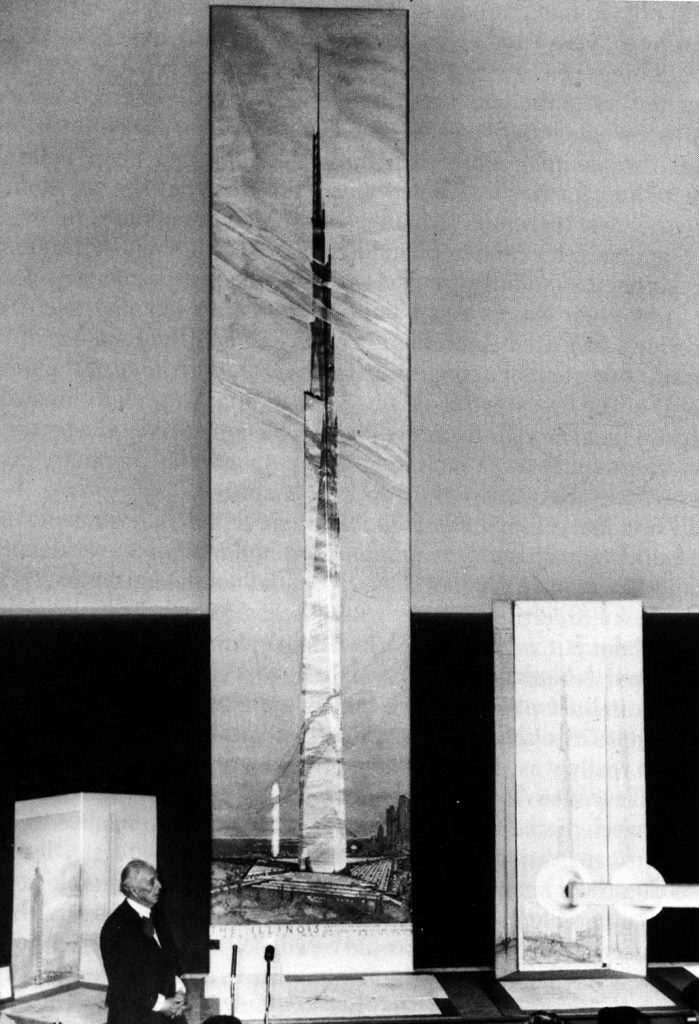

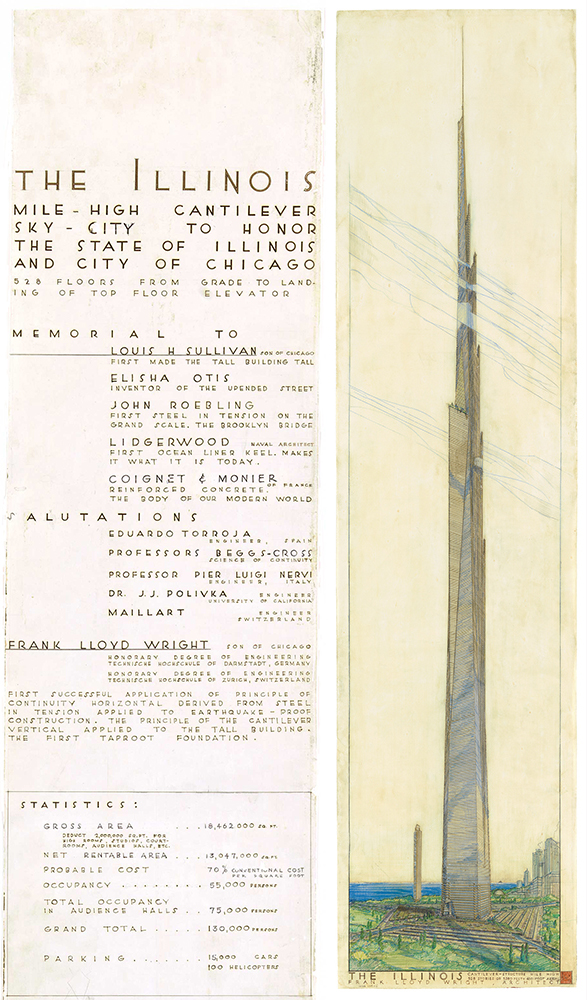

Also known as the Illinois Mile-High Tower, Wright’s skyscraper would stand 528 floors and 5,280 feet (1,609 meters) tall plus antenna; more than four times the height of the Empire State Building in New York City, then the tallest skyscraper in the world at 102 floors and 1,250 feet (380 meters) tall plus antenna. At the unveiling of The Illinois at the Sherman House Hotel in Chicago, Wright presented an illustration measuring more than 25 feet (7.6 meters) tall, with the skyscraper drawn at the scale of 1/16 inch to the foot.

Basic parameters for The Illinois are listed below:

- Floors, above grade level: 528

- Height:

- Architectural: 5,280 ft (1,609.4 m)

- To tip of antenna: 5,706 ft (1739.2 m)

- Number of elevators: 76

- Gross floor area (GFA): 18,460,106 ft² (1,715,000 m²)

- Number of occupants: 100,000

- Number of parking spaces: 15,000

- Structural material:

- Core: Reinforced concrete

- Cantilevered floors: Steel

- Tensioned tripod: Steel

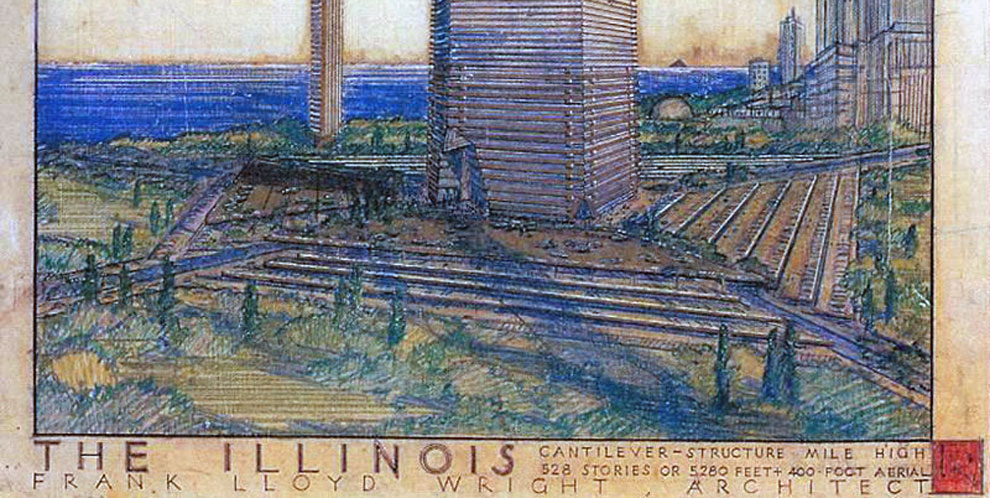

The Illinois was intended as a mixed-use structure designed to spread urbanization upwards rather than outwards. The Illinois offered nearly three times the gross floor area (GFA) of the Pentagon, and more than seven times the GFA of the Empire State Building for use as office, hotel, residential and parking space. Wright said the building could consolidate all government offices then scattered around Chicago.

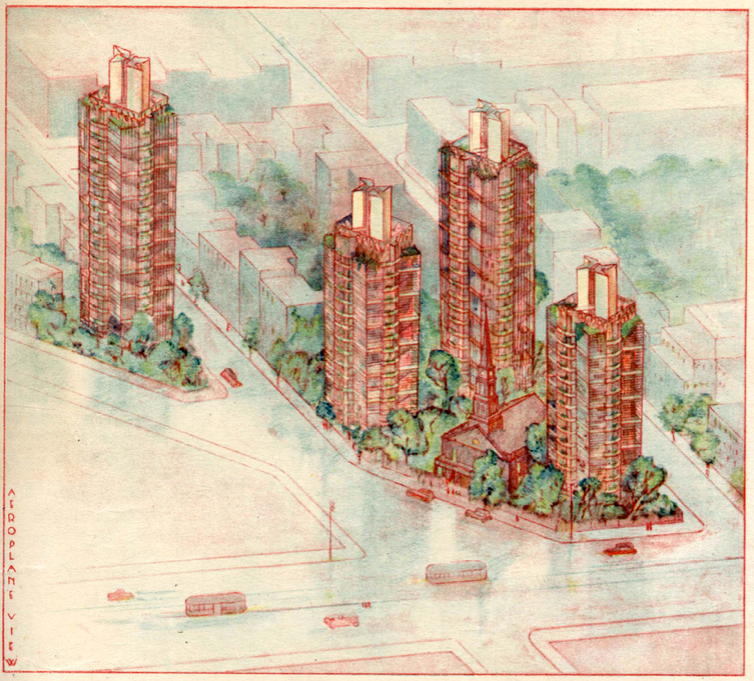

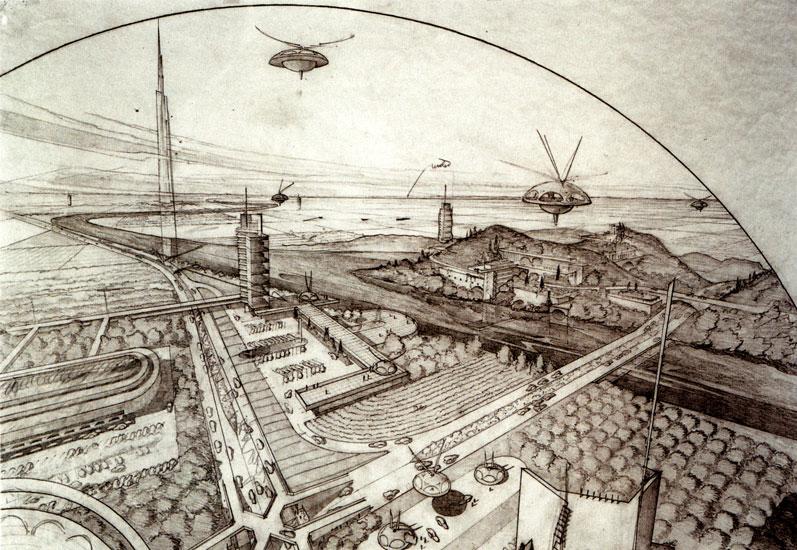

The single super-tall skyscraper was intended to free up the ground plane by eliminating the need for other large skyscrapers in its vicinity. This was consistent with Wright’s distributed urban planning concept known as Broadacre City, which he introduced in the mid-1930s and continued to advocate until his death in 1959.

The Illinois. Source: Wright Mile Gallery, MCM Daily

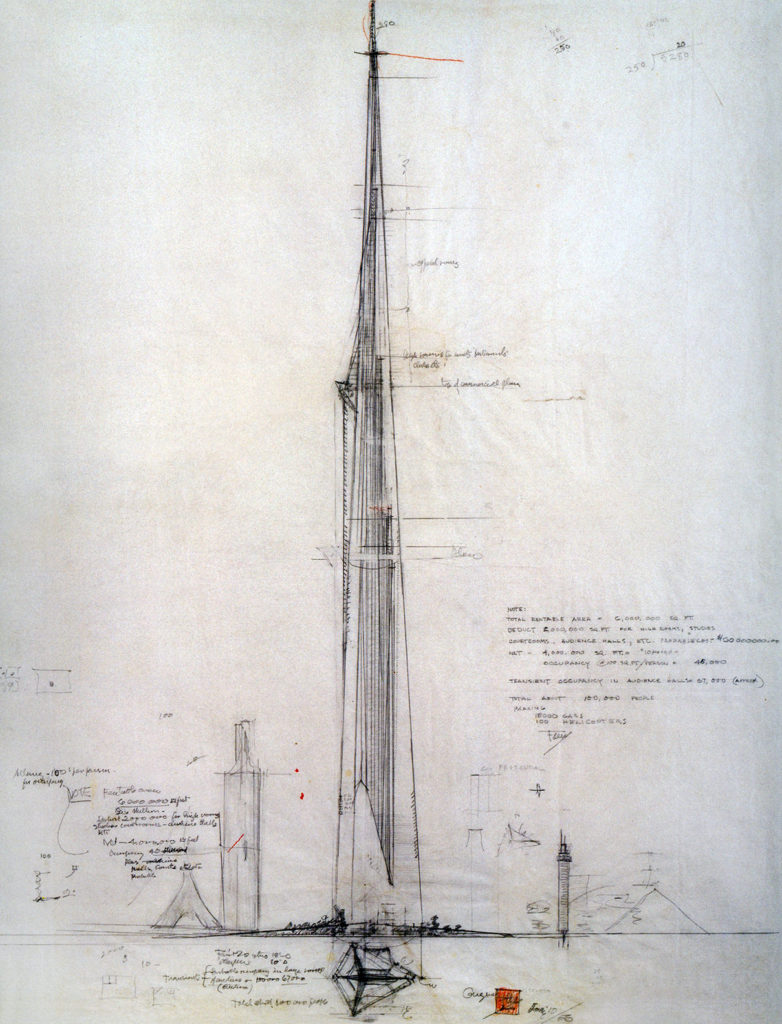

Source: https://www.artbook.com/blog-frank-lloyd-wright-skyscraper.html

L to R: Cross-section; Back exterior view; Front exterior view; Side exterior view.

Source: Wright Mile Gallery, MCM Daily

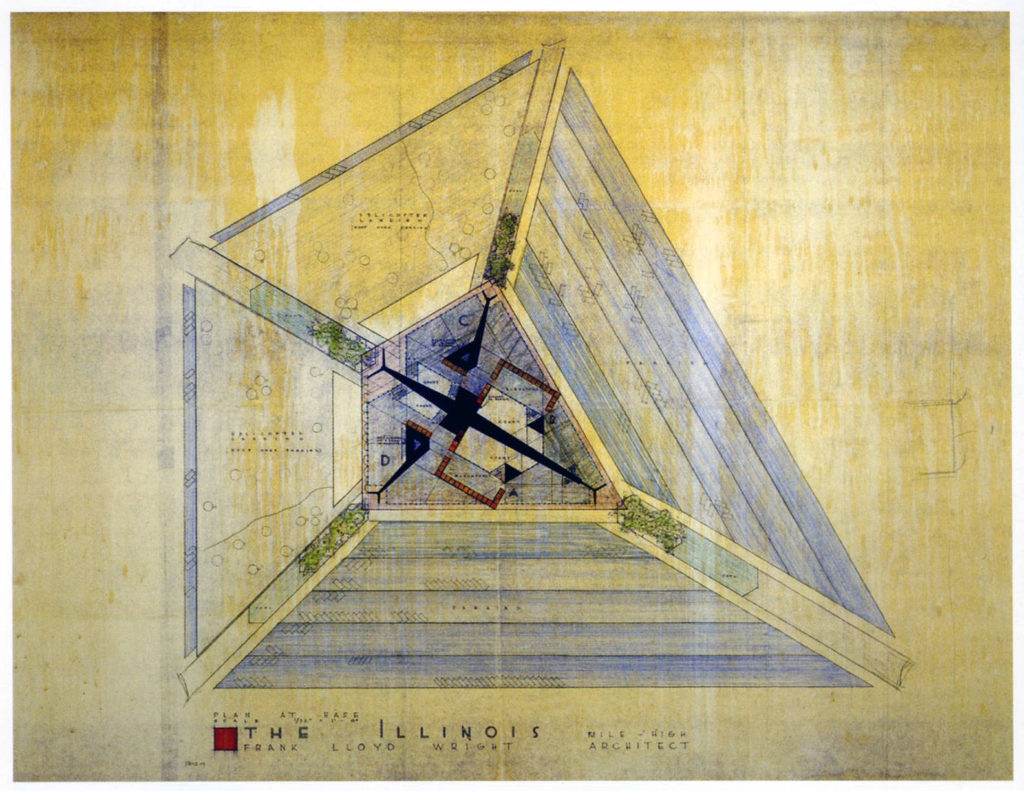

Source: Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

Source: Source: Wright Mile Gallery, MCM Daily

2. Tenuity, continuity and evolution of Wright’s concept for an organic high-rise building

Two aspects of Wright’s concept of organic architecture are the structural principles he termed “tenuity” and “continuity,” both of which he applied in the context of cantilevered and cable-supported structures, such as slender buildings and bridges. Author Richard Cleary reported that Wright first used the term tenuity in his 1932 book Autobiography, and offered his most succinct explanation in his 1957 book Testament.

- “The cantilever is essentially steel at its most economical level of use. The principle of the cantilever in architecture develops tenuity as a wholly new human expression, a means, too, of placing all loads over central supports, thereby balancing extended load against opposite extended load.”

- “This brought into architecture for the first time another principle in construction – I call it continuity – a property which may be seen as a new, elastic, cohesive, stability. The creative architect finds here a marvelous new inspiration in design. A new freedom involving far wider spacing of more slender supports.”

- “Thus architecture arrived at construction from within outward rather than from outside inward; much heightening and lightening of proportions throughout all building is now economical and natural, space extended and utilized in a more liberal planning than the ancients could ever have dreamed of. This is now the prime characteristic of the new architecture called organic.”

- “Construction lightened by means of cantilevered steel in tension makes continuity a most valuable characteristic of architectural enlightenment.”

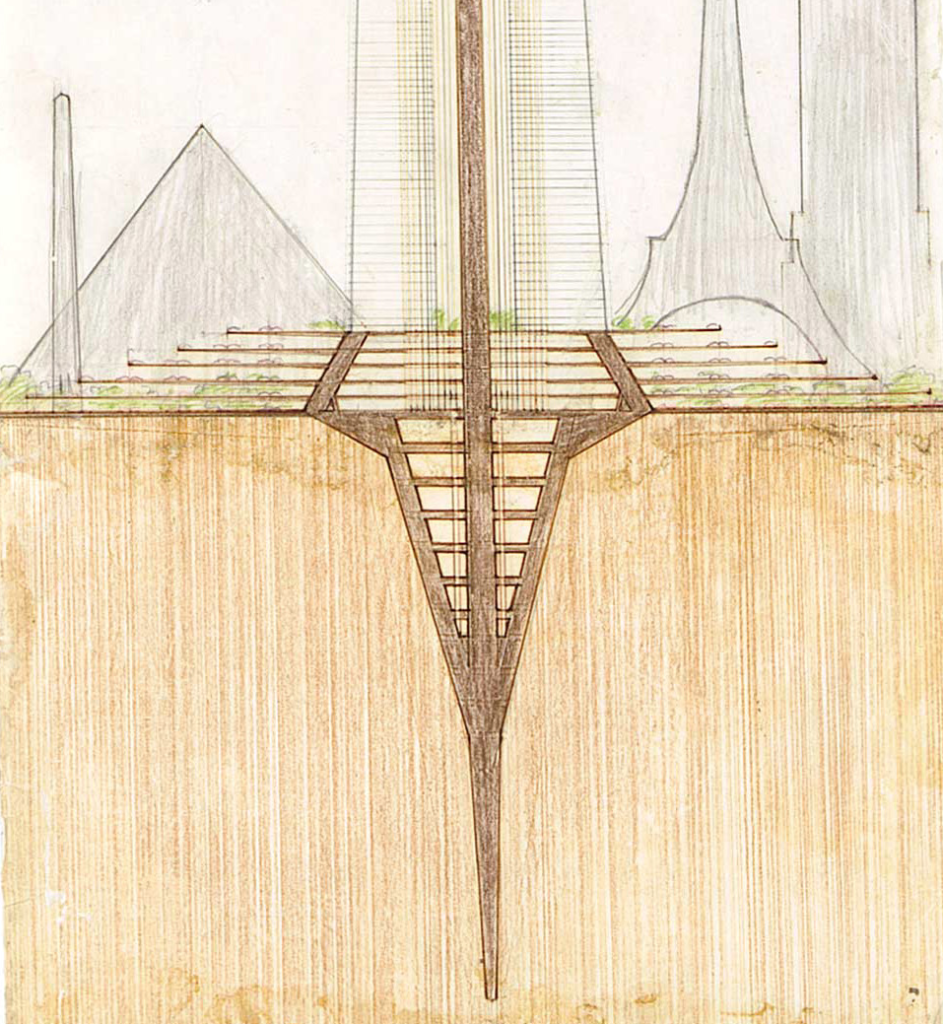

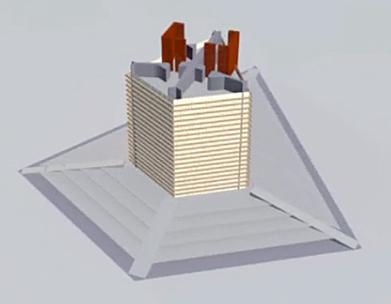

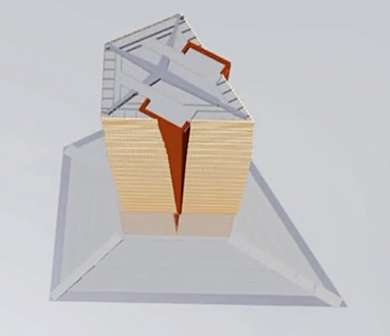

The structural principles of tenuity and continuity are manifest in Wright’s high-rise building designs that are characterized by a deep “taproot” foundation that supports a central load bearing core structure from which the individual floors are cantilevered. A cross-section of the resulting building structure has the appearance of a tree deeply rooted in the Earth with many horizontal branches.

Before looking further at the Mile-High Skyscraper, we’ll take a look at three of its high-rise predecessors and one later design, all of which shared Wright’s characteristic organic architectural features derived from the application of tenuity and continuity: taproot foundation, load-bearing core structure and cantilevered floors:

- St. Mark’s Tower project

- SC Johnson Research Tower

- Price Tower

- The Golden Beacon

St. Mark’s Tower project (St. Mark’s-in-the-Bouwerie, 1927 – 1931, not built)

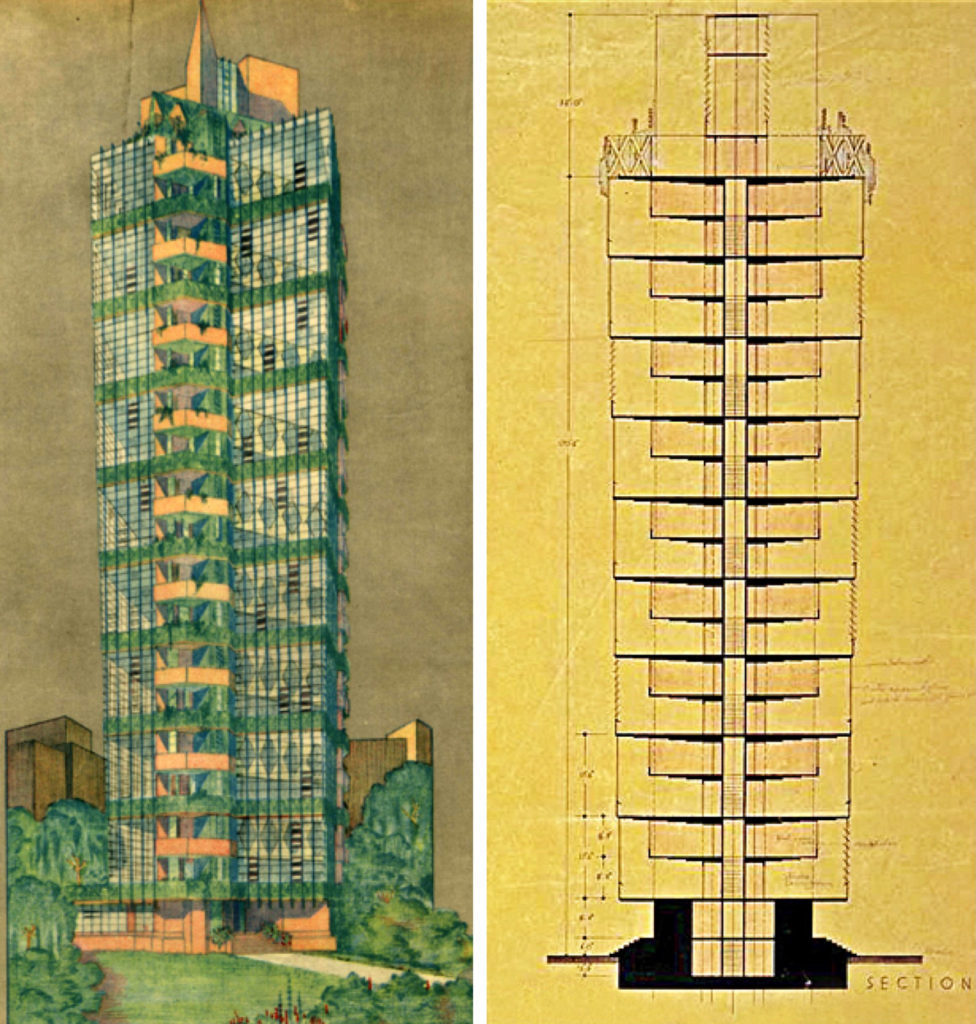

Wright first proposed application of the taproot foundation, load-bearing concrete and steel core structure and cantilevered floors was in 1927 for the 15-floor St. Mark’s Tower project in New York City.

Sources: (L) Architectural Record, 1930, via The New Yorker;

(R) adapted from Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation drawing

The New York Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) provides this description of the St. Mark’s Tower project.

- “The design of these apartment towers for St. Mark’s-in-the-Bouwerie in New York City stemmed from Wright’s vision for Usonia, a new American culture based on the synthesis of architecture and landscape. The organic “tap-root” structural system resembles a tree, with a central concrete and steel load-bearing core rooted in the earth, from which floor plates are cantilevered like branches.”

- “This system frees the building of load-bearing interior partitions and supports a modulated glass curtain wall for increased natural illumination. Floor plates are rotated axially to generate variation from one level to the next and to distinguish between living and sleeping spaces in the duplex apartments.”

While the St. Mark’s Tower project was not built, this basic high-rise building design reappeared from the mid-1930s to the mid-1960s as a “city dweller’s unit” in Wright’s Broadacre City plan and was the basis for the Price Tower built in the 1950s.

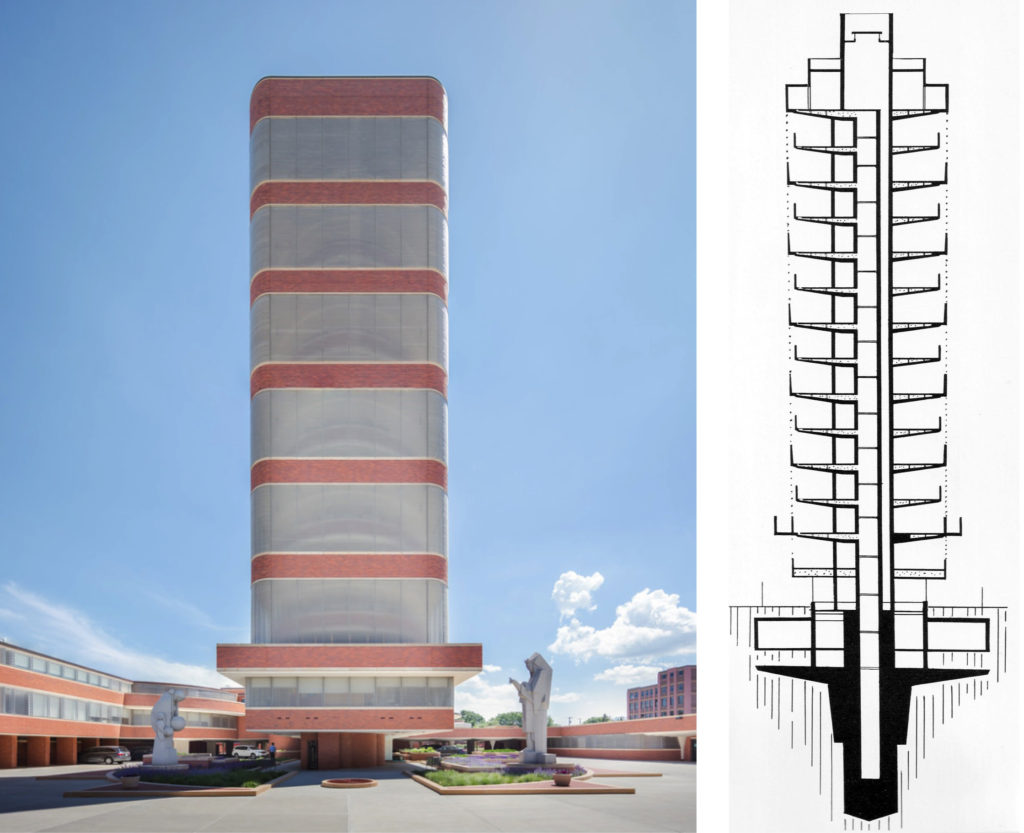

SC Johnson Research Tower, Racine, WI (1943 – 1950)

The 15-floor, 153 foot (46.6 m) tall SC Johnson Research Laboratory Tower, built between 1943 and 1950 in Racine, WI, was the first high-rise building to actually apply Wright’s organic design with a taproot foundation, load-bearing concrete and steel core structure and cantilevered floors. On their website, SC Johnson describes the structural design of this building as follows:

- “One of Frank Lloyd Wright’s famous buildings, the tower rises more than 150 feet into the air and is 40 feet square. Yet at ground level, it’s supported by a base only 13 feet across at its narrowest point. As a result, the tower almost seems to hang in the air – a testament to creativity and an inspiration for the innovative products that would be developed inside.”

- “Alternating square floors and round mezzanine levels make up the interior, and are supported by the “taproot” core, which also contains the building’s elevator, stairway and restrooms. The core extends 54 feet into the ground, providing stability like the roots of a tall tree.”

(R) https://www.scjohnson.com

Because of the change in fire safety codes, and the impracticality of retrofitting the building to meet current code requirements, SC Johnson has not used the Research Tower since 1982. However, they restored the building in 2013 and now the public can visit as part of the SC Johnson Campus Tour.

You can make reservations at the following link for the Campus Tour and a separate tour of the nearby Herbert F. Johnson Prairie-style home, Wingspread, also designed by Frank Lloyd Wright: https://reservations.scjohnson.com/Info.aspx?EventID=8

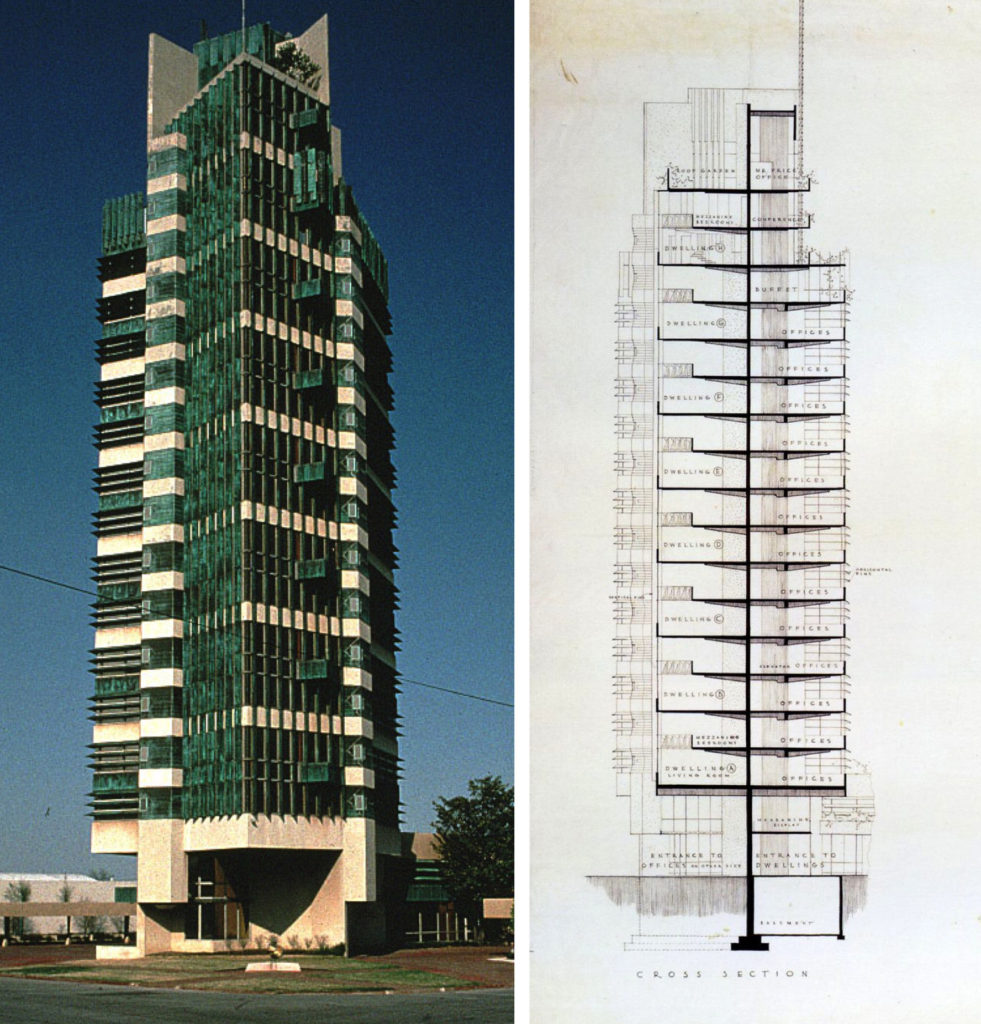

Price Tower, Bartlesville, OK (1952 – 1956)

The 19-floor, 221 foot (67.4 m) tall Price Tower, completed in 1956 in Bartlesville, OK, is an evolution of Wright’s 1927 design for the St. Mark’s Tower project. Wright nicknamed the Price Tower, “the tree that escaped the crowded forest,” referring to the building’s cantilever construction and the origin of its design in a project for New York City. Price Tower also has been called the “Prairie Skyscraper.”

Sources: (L) http://www.greatbuildings.com/

(R) https://mgerwingarch.com/m-gerwing/2012/05/28/price-tower

H.C. Price commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design Price Tower, which served as his corporate headquarters until 1981 when it was sold to Phillips Petroleum. Philips deemed the exterior exit staircase a safety risk and only used the building for storage until 2000, when the building was donated to the Price Tower Arts Center. Since then, Price Tower has been returned to its multi-use origins and public tours are offered, including a visit to the restored 19th floor executive office of H.C. Price and the H.C. Price Company corporate apartment with the original Wright interiors. You can arrange your tour here: https://www.pricetower.org/tour/

You also can stay at the Inn at Price Tower, which has seven guest rooms. You’ll find details here: https://www.pricetower.org/stay/

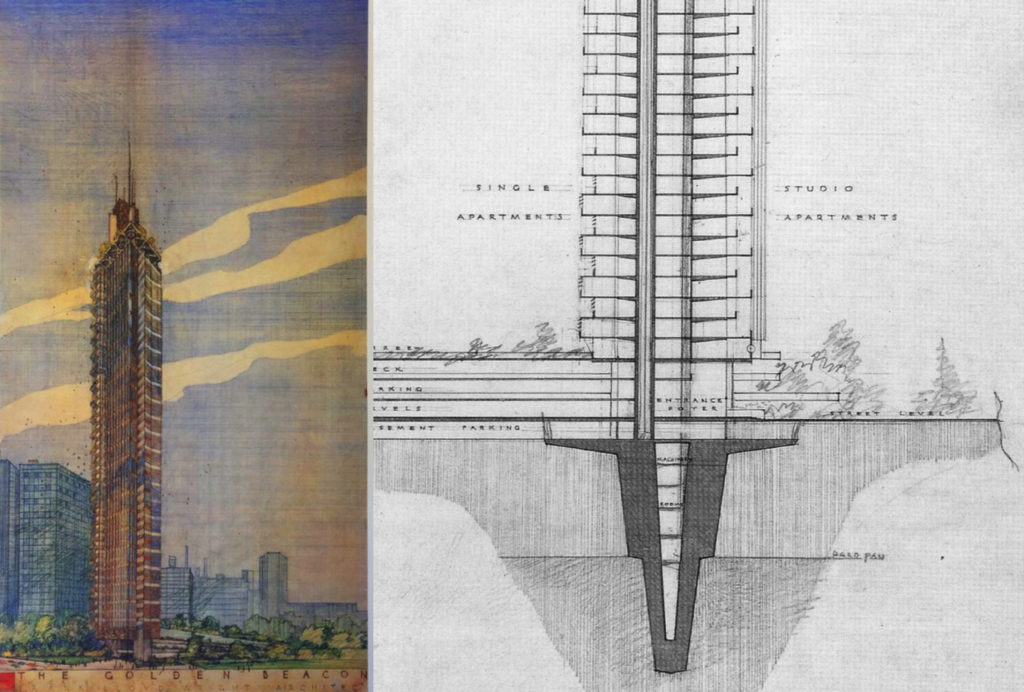

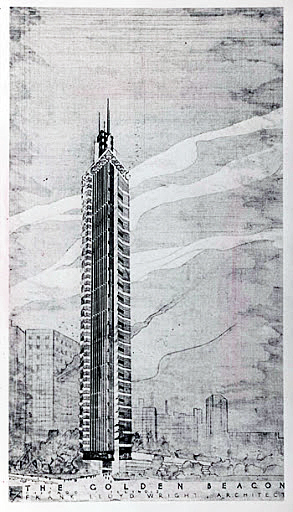

The Golden Beacon, Chicago, IL (1959, not built)

The Golden Beacon was a concept for a 50-floor mixed-use office and residential apartment building in Chicago, IL.

central core and cantilever floors. (R).

Sources: (L) https://stoutbooks.com/, (R) Richard Cleary, “Lessons in Tenuity….”

As shown in the cross-section diagram, the building design followed Wright’s practice with a deep taproot foundation, a central load-bearing core and cantilevered floors. This design is very similar to the foundation structure proposed for the earlier Mile-High Skyscraper.

3. Extrapolating to the Mile-High Skyscraper

By 1956, Wright’s characteristic organic architectural features for high-rise buildings, derived from the application of tenuity and continuity, had only appeared in two completed high-rise buildings, the 15-floor SC Johnson Laboratory Tower and the 19-floor Price Tower. These two important buildings demonstrated the practicality of the taproot foundation, load-bearing concrete and steel core structure and cantilevered floors for tall, slender buildings. With the unveiling of The Illinois, Wright made a remarkable extrapolation of these architectural principles in his conceptual design of this breathtaking 528 floor, 5,280 feet (1,609 meters) tall skyscraper.

Blaire Kamin, writing for the Chicago Tribune in 2017, reported: “The Mile-High didn’t simply aim to be tall. It was the ultimate expression of Wright’s “taproot” structural system, which sank a central concrete mast deep into the ground and cantilevered floors from the mast. In contrast to a typical skyscraper, in which same-size floors are piled atop one another like so many pancakes, the taproot system lets floors vary in size, opening a high-rise’s interior and letting space flow between floors.”

In addition to the central core to support the building’s dead loads, The Illinois also incorporated an external tensioned steel tripod structure to resist external wind loads and other flexing loads (i.e., earthquakes), distributing those loads through the integral steel structure of the tripod, and resisting oscillations. In his book, “Testament,” Wright stated:

“Finally – throughout this lightweight tensilized structure, because of the integral character of all members, loads are at equilibrium at all points, doing away with oscillations. There would be no sway at the peak of The Illinois.”

Tuned mass dampers (TMD) for reducing the amplitude of mechanical vibrations in tall buildings had not been invented when Wright unveiled his design for The Illinois in 1956. The first use of a TMD in a skyscraper did not occur until the mid-1970s, first as a retrofit to the troubled, 790 foot (241 m) tall, John Hancock building completed in 1976 in Boston, and then as original equipment in the 915 foot (279 m) tall Citicorp Tower completed in 1977 in New York City. While tenuity and continuity may have given The Illinois unparalleled structural stability, I wouldn’t be surprised if TMD technology would have been needed for the comfort of the occupants on the upper floors, three-quarters of a mile above their counterparts in the next tallest building in the world.

To handle its 100,000 occupants, The Illinois had 76 elevators that were divided into five groups, each serving a 100-floor segment of the building, with a single elevator serving only the top floors. Each elevator was a five-story unit that moved on rails and served five floors simultaneously. With the tapering, pyramidal shape of the skyscraper, the vertical elevator shaft structures eventually extended beyond the sloping exterior walls, forming protruding parapets on the sides of the building. In his 1957 book, “A Testament,” Wright said the elevators were designed to enable building evacuation within one hour, in combination with the escalators that serve the lowest five floors.

Wright alluded to the building (and the elevators) being “atomic powered,” but there were no provisions for a self-contained power plant as part of the building. The much smaller Empire State Building currently has a peak electrical demand of almost 10 megawatts (MW) in July and August after implementing energy conservation measures. Scaling on the basis of gross floor area, The Illinois could have had a peak electrical demand of about 70 MW. You’ll find more information on current Empire State Building energy usage here: https://www.esbnyc.com/sites/default/files/esb_overall_retrofit_fact_sheet_final.pdf

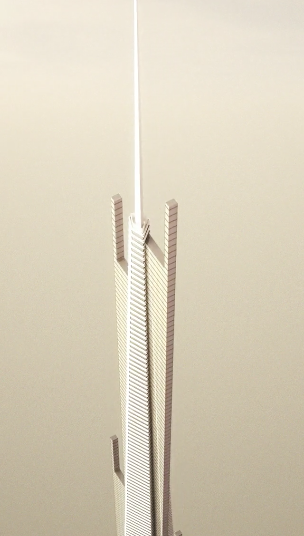

The 2012 short video by Charles Muench, “A Peaceful Day in BroadAcre City – One Mile High – Frank Lloyd Wright” (1:31 minutes), depicts The Illinois skyscraper in the spacious setting of Broadacre City and shows an animated construction sequence of the tower. Two screenshots from the video are reproduced below. You’ll find this video at the following link: https://www.dailymotion.com/video/xp86uo

Screenshots from Charles Muench video, 2012.

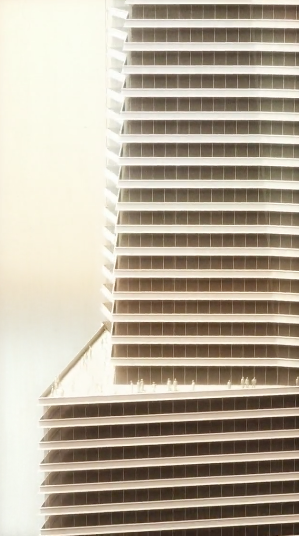

You can see more architectural details in the 2009 video, “Mile High Final Movie – Frank Lloyd Wright” (3:42 minutes), produced for the Guggenheim Museum, New York. Two screenshots are reproduced below. You’ll find the video here: https://vimeo.com/4937909

Screenshot from Guggenheim video, 2009.

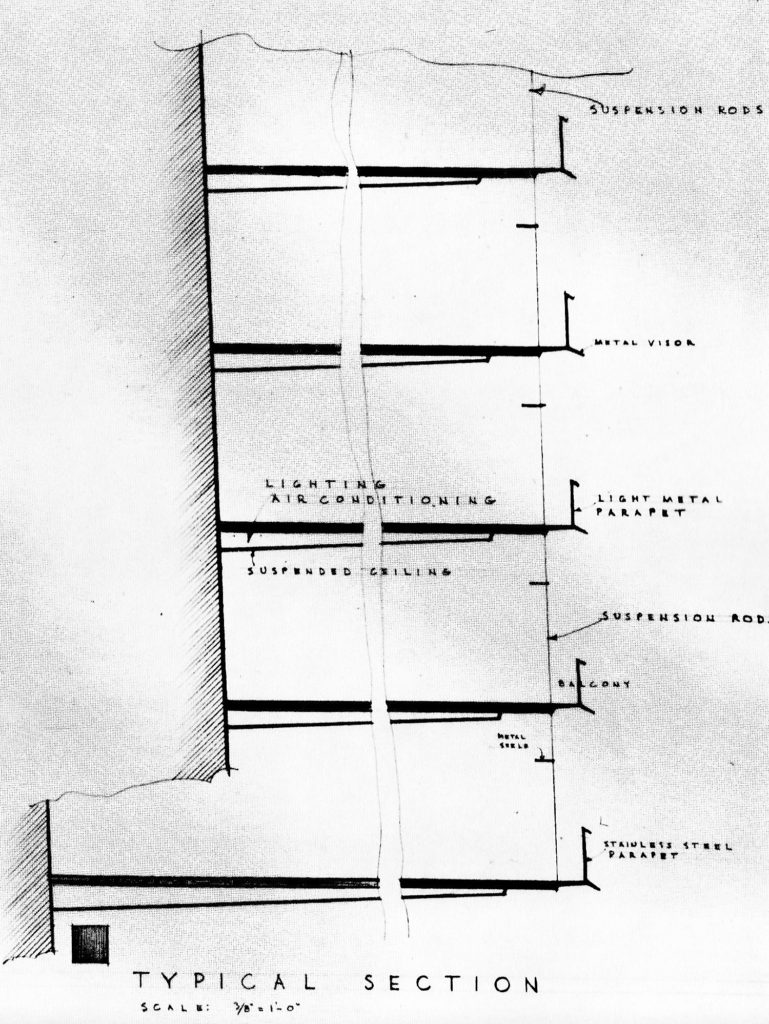

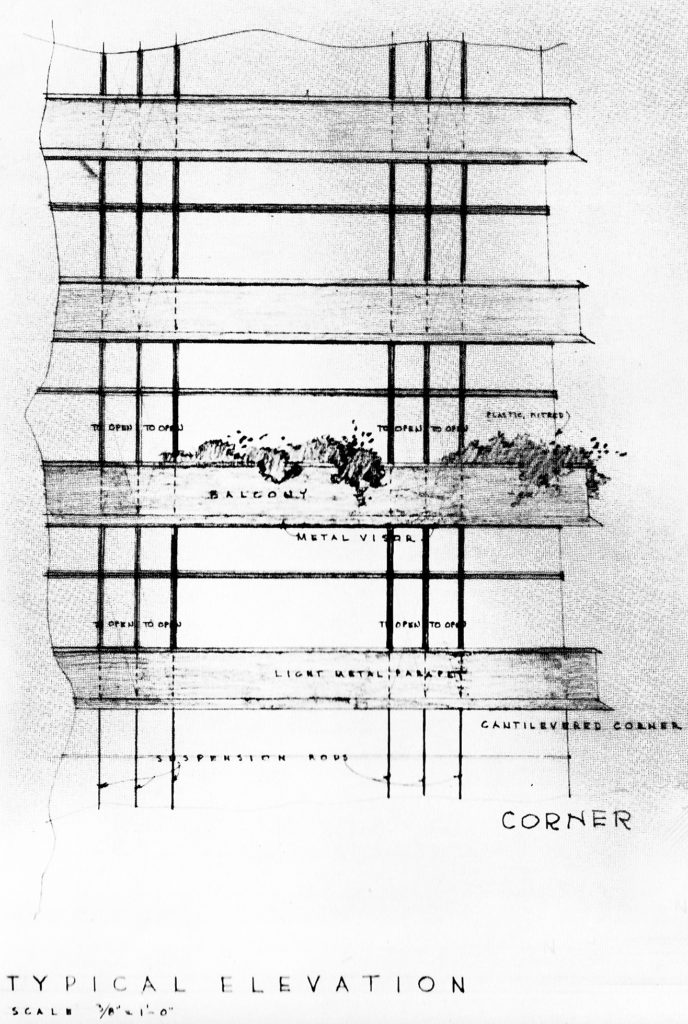

In his 1957 book, Testament, Wright provided the following two architectural drawings showing typical details of the cantilever construction of The Illinois.

The Illinois was intended for construction in a spacious setting like Broadacre City, rather than in a congested big-city downtown immediately adjacent to other skyscrapers. Two views of The Illinois in these starkly different settings are shown below.

4. Wright’s Mile-High Skyscraper on Exhibit at MoMA

Since Wright’s death in 1959, his archives have been in the care of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation (https://franklloydwright.org/frank-lloyd-wright/) and stored at Wright’s homes / architectural schools at Taliesin in Spring Green, WI and Taliesin West, near Scottsdale, AZ.

In September 2012, Mary Louise Schumacher, writing for the Milwaukee Sentinel Journal, reported that Columbia University and the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in Manhattan had jointly acquired the Frank Lloyd Wright archives, which consist of architectural drawings, large-scale models, historical photographs, manuscripts, letters and other documents. You’ll find her report here: http://archive.jsonline.com/newswatch/168457936.html

Columbia University’s Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library (https://library.columbia.edu/libraries/avery/da.html) will be the keeper of all of Wright’s paper archives, as well as interview tapes, transcripts and films. MoMA (https://www.moma.org) will add Wright’s three-dimensional models to its permanent collection.

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation will retain all copyright and intellectual property responsibilities for the archives, and all three organizations hope to see the archives placed online at some point in the future.

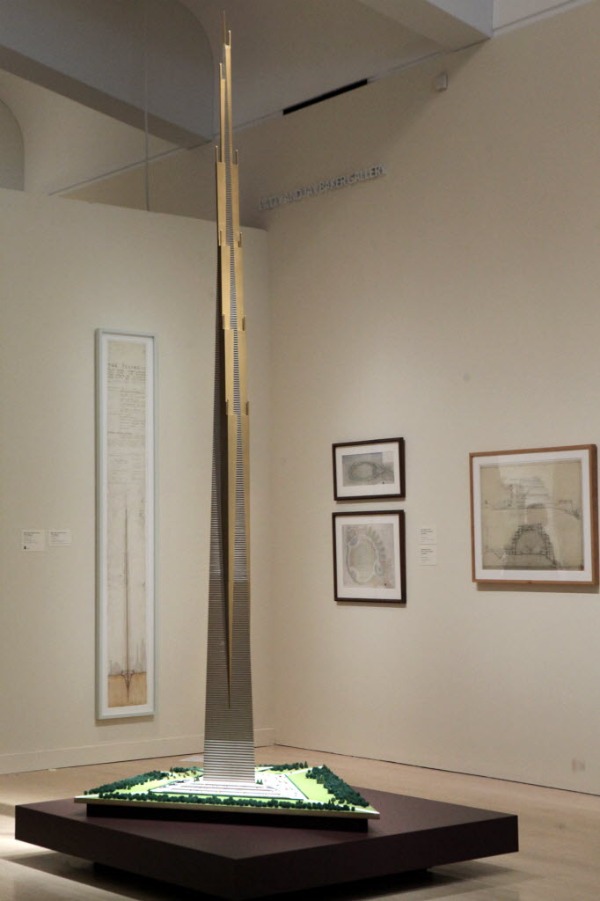

On 12 June 2017, MoMA opened its exhibit, “Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive,” which ran thru 1 October 2017. You can take an online tour of this exhibit, which included Wright’s plans for The Illinois, here: https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1660

MoMA’s curator of the Wright collection, Barry Bergdoll, provided an introduction to the trove of recently acquired documentation on The Illinois in a short 2017 video (4:32 minutes) at the following link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VhUDu0Q08UA

2017 MoMA exhibit. Source: MoMA

You can download a pdf copy of this article here: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Frank-Lloyd-Wright_-1956-Mile-High-Skyscraper_R1.pdf

5. For more information

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Mile-High Skyscraper, The Illinois:

- “Frank Lloyd Wright Day and The Mile High Building ‘The Illinois’,” The Wright Library: http://www.steinerag.com/flw/Books/sixty.htm#MileHigh

- Wright Mile Gallery, MCM Daily, https://www.mcmdaily.com/gallery/wright-mile-gallery/

- Richard Cleary, “Lessons in Tenuity: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Bridges,” https://www.arct.cam.ac.uk/Downloads/ichs/vol-1-741-758-cleary.pdf

- Justine Jablonska, “Frank Lloyd Wright got the future of cities wrong,” IBM, 16 October 2017: https://www.ibm.com/blogs/industries/frank-lloyd-wright-got-future-cities-wrong/

- Blair Kamin, “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Mile-High skyscraper never built, but never forgotten,” Chicago Tribune, 28 May 2017: https://www.chicagotribune.com/columns/ct-frank-lloyd-wright-mile-high-met-0528-20170528-column.html

Frank Lloyd Wright’s concept for Broadacre City:

- “Broadacre City,” including St. Mark’s Tower project, The Wright Library: http://www.steinerag.com/flw/Artifact%20Pages/PhBroadacre.htm

- “Introduction to Frank Lloyd Wright and Broadacre City,” Utopicus: http://utopicus2013.blogspot.com/2013/06/introduction-to-frank-lloyd-wright-and.html

- “Frank Lloyd Wright Designs an Urban Utopia: See His Hand-Drawn Sketches of Broadacre City (1932),” OpenCulture, 21 September 2016: http://www.openculture.com/2016/09/frank-lloyd-wright-designs-an-urban-utopia-see-his-hand-drawn-sketches-of-broadacre-city-1932.html

Frank Lloyd Wright’s related organic high-rise building designs:

- “St. Mark’s Tower project, New York, NY,” MoMA: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/305

- The Price Tower (1952) S.355,” The Wright Library: http://www.steinerag.com/flw/Books/PriceTower.htm

- “Price Tower,” M. Gerwing Architects, 28 May 2012: https://mgerwingarch.com/m-gerwing/2012/05/28/price-tower

- Experience Price Tower, Price Tower Arts Center: https://www.pricetower.org

- S.C. Johnson Research Tower(1944), Racine, Wisconsin: https://www.findingmrwright.com/17-buildings/johnson-research/

Also check out the following short videos:

- Justin Chen, “Mile High Office Tower: Student Animation” (1:53 minutes), Guggenheim Museum, New York, 3 June 2010: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nRgICz41m_U

- Professor Allen Sayegh with Justin Chen & John Pugh, “Mile High Final Movie – Frank Lloyd Wright” (3:42), Harvard University Graduate School of Design for the Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2009: https://vimeo.com/4937909

- Stefan Al, “Will there ever be a mile-high skyscraper” (4:45 minutes), TED Talks, 7 February 2019: https://www.ted.com/talks/stefan_al_will_there_ever_be_a_mile_high_skyscraper/transcript?language=en

- “Frank Lloyd Wright – SC Johnson Research Tower, Racine, Wisconsin” (7:05 minutes), #franklloydwright, 12 September 2017: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m1CkuXYizQc