Peter Lobner, updated 13 September 2023

1. Introduction

To date, only Russia, the U.S. and China have accomplished soft landings on the Moon, with each nation using a launch vehicle and spacecraft developed within their own national space programs.

On 8 October 2020, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid announced the formation of the UAE’s lunar rover program, which intends to accomplish the first moon landing for the Arab world using the commercial services of a U.S. SpaceX Falcon 9 launch vehicle and a Japanese ispace lunar landing vehicle named HAKUTO-R. Once on the lunar surface, the UAE’s Rashid rover will be deployed to perform a variety of science and exploration tasks. This mission was launched from Cape Canaveral on 11 December 2022.

Source: MBRSpaceCenter tweet

2. Japan’s ispace HAKUTO-R lunar lander

The Japanese firm ispace, inc. was founded in September 2010, with headquarters in Tokyo, a U.S. office in Denver, CO, and a European office in Luxembourg. Their website is here: https://ispace-inc.com

ispace’s HAKUTO team was one of six finalist teams competing for the Google Lunar XPRIZE. On 15 December 2017, XPRIZE reported,” Congratulations to Google Lunar XPRIZE Team HAKUTO for raising $90.2 million in Series A funding toward the development of a lunar lander and future lunar missions! This is the biggest investment to date for an XPRIZE team, and sends a strong signal that commercial lunar exploration is on the trajectory to success. One of the main goals of the Google Lunar XPRIZE is to revolutionize lunar exploration by spurring innovation in the private space sector, and this announcement demonstrates that there is strong market interest in innovative robotic solutions for sustainable exploration and development of the Moon. The XPRIZE Foundation looks forward to following Team HAKUTO as they progress toward their lunar mission!”

The Google Lunar XPRIZE was cancelled when it became clear that none of the finalist teams could meet the schedule for a lunar landing in 2018 and other constraints set for the competition. Consequently, Team HAKUTO’s lander was not flown on a mission to the Moon.

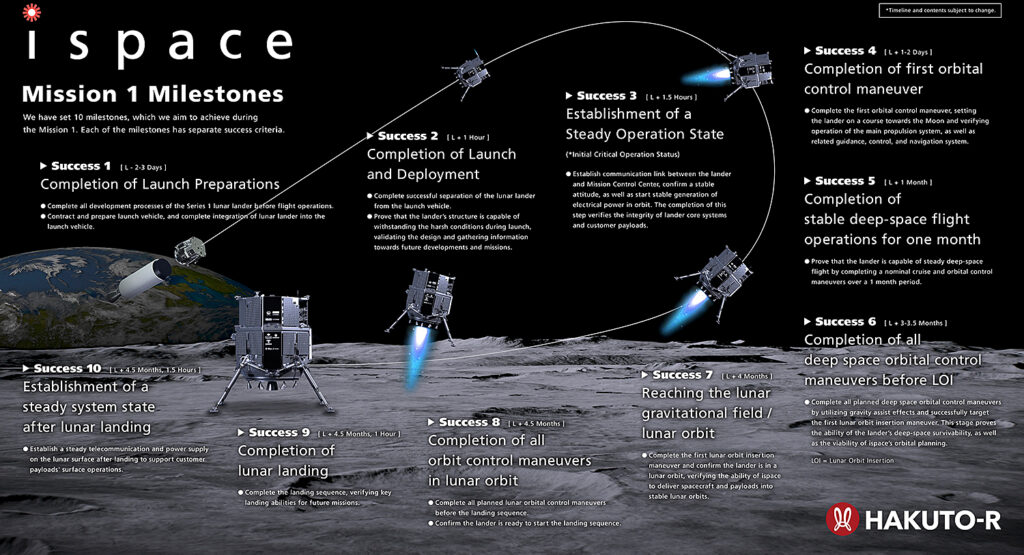

In April 2021, the Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Center (MBRSC) of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) signed a contract with ispace, under which ispace agreed to provide commercial payload delivery services for the Emirates Lunar Mission. After final testing in Germany, the ispace SERIES-1 (S1) lunar lander was ready in 2022 for the company’s ‘Mission 1,’ as part of its commercial lunar landing services program known as ‘HAKUTO-R’.

It is more than 7 feet (2.3 meters) tall. Source: ispace

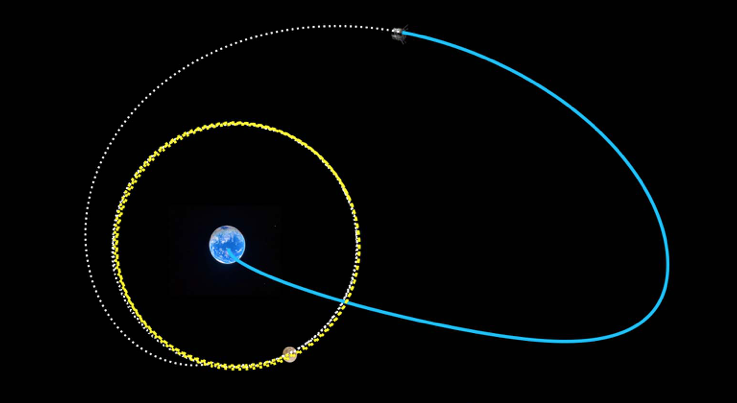

After its launch on 11 December 2022, the lunar spacecraft has been flying a “low energy” trajectory to the Moon in order to minimize fuel use during the transit and, hence, maximizes the available mission payload. It will take nearly five months for the combined lander / rover spacecraft to reach the Moon in April 2023.

Source: ispace

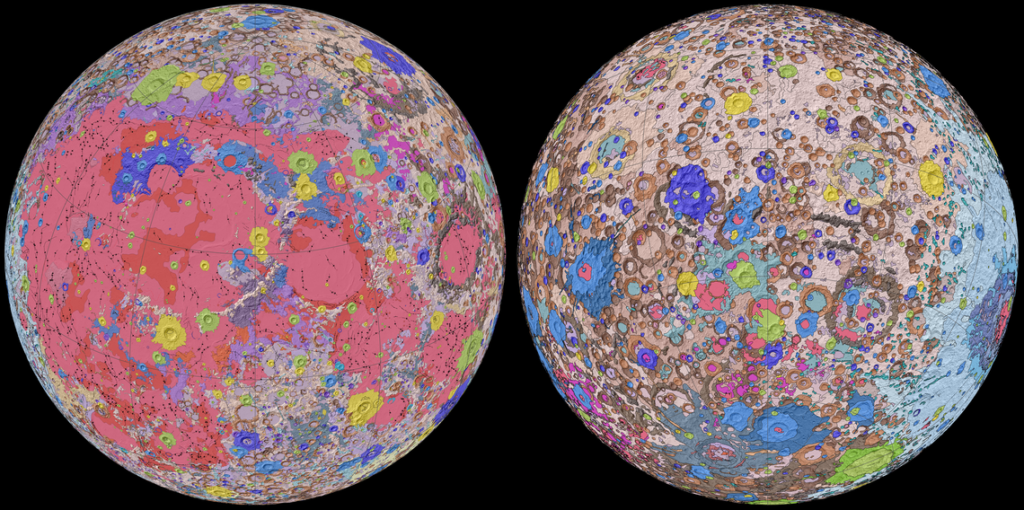

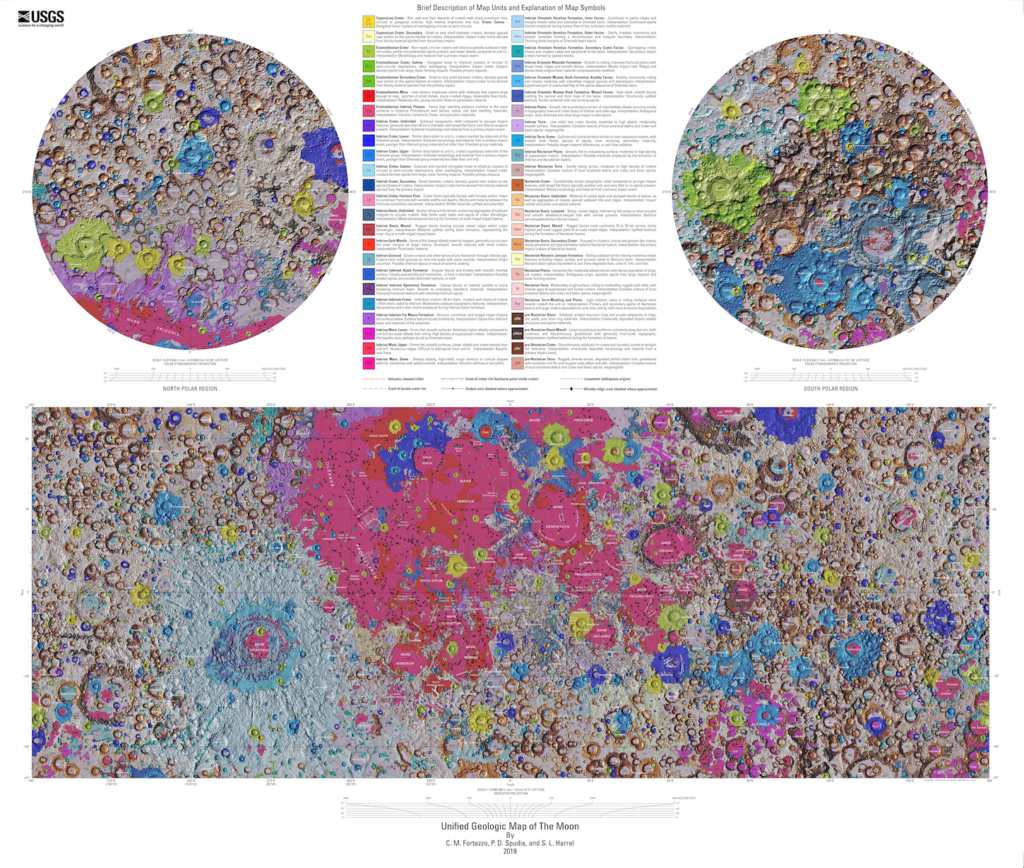

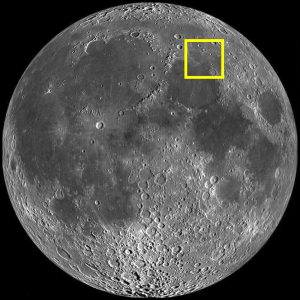

The primary landing site is the Atlas crater in Lacus Somniorum (Lake of Dreams), which is a basaltic plain formed by flows of basaltic lava, located in the northeastern quadrant of the moon’s near side.

Source: The Lunar Registry

If successful, HAKUTO-R will also become the first commercial spacecraft ever to make a controlled landing on the moon.

After landing, the UAE’s Rashid rover will be deployed from the HAKUTO-R lander. In addition, the lander will deploy an orange-sized sphere from the Japanese Space Agency that will transform into a small wheeled robot that will move about on the lunar surface.

3. UAE’s Rashid lunar rover

The Emirates Lunar Mission (ELM) team at the Mohammed bin Rashid Space Centre (MBRSC) is responsible for designing, manufacturing and developing the rover, which is named Rashid after Dubai’s royal family. The ELM website is here: https://www.mbrsc.ae/service/emirates-lunar-mission/

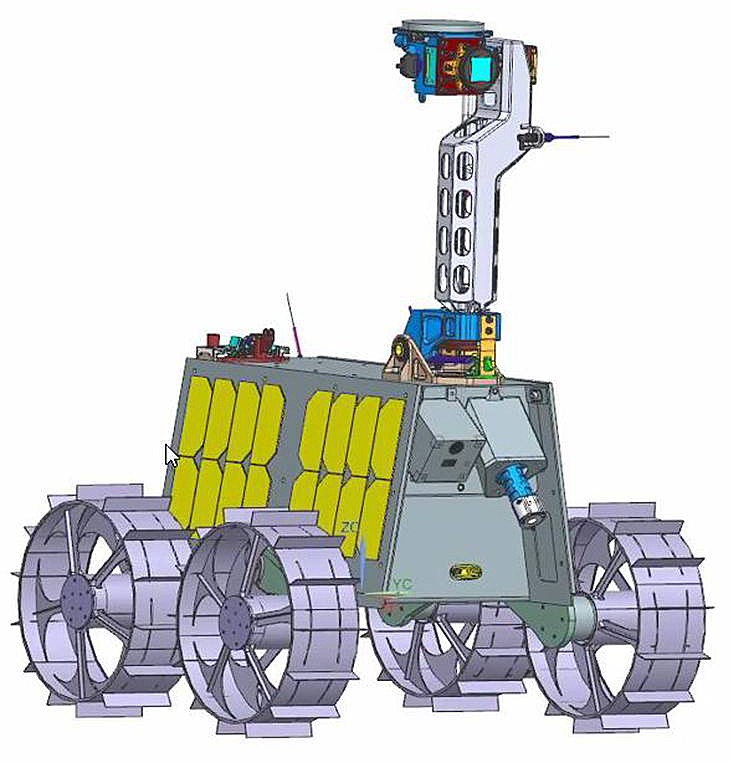

The Rashid rover weighs just 22 pounds (10 kilograms) and, with four-wheel drive, can traverse a smooth surface at a maximum speed of 10 cm/sec (0.36 kph) and climb over an obstacle up to 10 cm (3.9 inches) tall and descend a 20-degree slope.

The Rashid rover is designed to operate on the Moon’s surface for one full lunar day (29.5 Earth days), during which time it will conduct studies of the lunar soil in a previously unexplored area. In addition, the rover will conduct engineering studies of mobility on the lunar surface and susceptibility of different materials to adhesion of lunar particles. The outer rims of this rover’s four wheels incorporate small sample panels to test how different materials cope with the abrasive lunar surface, including four samples contributed by the European Space Agency (ESA).

The diminutive rover carries the following scientific instruments:

- Two high-resolution optical cameras (Cam-1 & Cam-2) are expected to take more than 1,000 still images of the Moon’s surface to assess the how lunar dust and rocks are distributed on the surface.

- A “microscope” camera

- A thermal imaging camera (Cam-T) will provide data for determining the thermal properties of lunar surface material.

- Langmuir probes will analyze electric charge and electric fields at the lunar surface.

- An inertial measurement unit to track the motion of the rover.

Mobility and communications tests of the completed rover were conducted in March 2022 in the Dubai desert.

The Ottawa, Ontario company Mission Control Space Services has provided a deep-learning artificial intelligence (AI) system named MoonNet that will be used for identifying geologic features seen by the rover’s cameras. Mission Control Services reports, “Rashid will capture images of geological features on the lunar terrain and transmit them to the lander and into MoonNet. The output of MoonNet will be transmitted back to Earth and then distributed to science team members….Learning how effectively MoonNet can identify geological features, inform operators of potential hazards and support path planning activities will be key to validating the benefits of AI to support future robotic missions.”

Source: Mission Control Space Services

4. Landing attempt failed

The Hakuto-R lander crashed into the Moon on 25 April 2023 during its landing attempt.

In May 2023, the results of an ispace analysis of the landing failure were reported by Space.com:

“The private Japanese moon lander Hakuto-R crashed in late April during its milestone landing attempt because its onboard altitude sensor got confused by the rim of a lunar crater. the unexpected terrain feature led the lander’s onboard computer to decide that its altitude measurement was wrong and rely instead on a calculation based on its expected altitude at that point in the mission. As a result, the computer was convinced the probe was lower than it actually was, which led to the crash on April 25.”

“While the lander estimated its own altitude to be zero, or on the lunar surface, it was later determined to be at an altitude of approximately 5 kms [3.1 miles] above the lunar surface,” ispace said in a statement released on Friday (May 26). “After reaching the scheduled landing time, the lander continued to descend at a low speed until the propulsion system ran out of fuel. At that time, the controlled descent of the lander ceased, and it is believed to have free-fallen to the moon’s surface.”

On 23 May 2023, NASA reported that the its Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft had located the crash site of the UAE’s lunar spacecraft. The before and after views are shown in the following images.

Hakuto-R crash site, before (left) and after (right) the crash. Source: NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University

5. The future

ispace future lunar plans

ispace reported, “ispace’s SERIES-2 (S2) lander is designed, manufactured, and will be launched from the United States. While the S2 lander leverages lessons learned from the company’s SERIES-1 (S1) lander, it is an evolved platform representing our next generation lander series with increased payload capacity, enhanced capabilities and featuring a modular design to accommodate orbital, stationary or rover payloads.”

Ispace was selected through the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) initiative to deliver NASA payloads to the far side of the Moon using the SERIES-2 (S2) lander, starting in 2025.

UAE future lunar plans

In October 2022, the UAE announced that it was collaborating with China on a second lunar rover mission, which would be part of China’s planned 2026 Chang’e 7 lunar mission that will be targeted to land near the Moon’s south pole. These plans may be cancelled after the U.S. applied export restrictions in March 2023 on the Rashid 2 rover, which contains some US-built components. The U.S. cited its 1976 International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), which prohibit even the most common US-built items from being launched aboard Chinese rockets.

6. For more information

- Sarwat Nasir, “UAE to send lunar rover named Rashid to unexplored regions of Moon by 2024,” The National News, 8 October 2020: https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/science/uae-to-send-lunar-rover-named-rashid-to-unexplored-regions-of-moon-by-2024-1.1085377

- Mike Wehner, “UAE hires Japanese firm to launch its Moon rover in 2022,” bgr.com, 14 April 2021: https://bgr.com/science/lunar-rover-uae-moon-mission/

- Angel Tesorero, “Watch: Emirates Lunar Mission Tests Rashid Rover in Dubai Desert,” Gulf News, 9 March 2022: https://gulfnews.com/uae/science/watch-emirates-lunar-mission-tests-rashid-rover-in-dubai-desert-1.86314399

- Marcia Dunn, “Japanese company’s lander rockets toward moon with UAE rover,” AP News, 11 December 2022: https://apnews.com/article/science-business-tokyo-united-arab-emirates-national-aeronautics-and-space-administration-ad24fda20b214b21597593eb1d1fdd9d

- “ESA to touch Moon from wheels of UAE Rashid rover,” European Space Agency, 12 January 2023: https://www.esa.int/Enabling_Support/Space_Engineering_Technology/ESA_to_touch_Moon_from_wheels_of_UAE_Rashid_rover

- Elisabeth Howell, “UAE lunar rover will test 1st artificial intelligence on the moon with Canada,” Space.com. 28 January 2023: https://www.space.com/moon-artificial-intelligence-system-first-solar-system

- Andrew Jones, “Moon crash site found! NASA orbiter spots grave of private Japanese lander (photos),” Space.com, 23 May 2023: https://www.space.com/japan-hakuto-r-moon-lander-crash-site-found

- Tereza Pultarova, “Private Japanese moon lander crashed after being confused by a crater,” Space.com, 26 May 2023: https://www.space.com/moon-lander-ispace-hakuto-r-crash-lunar-terrain

Future missions

- “ispace Lunar Lander Selected to Deliver NASA CLPS Payloads to the Far Side of the Moon,” ispace press release, 25 July 2022: https://ispace-inc.com/news-en/?p=2436

- Mark Zastrow, “China and United Arab Emirates plan lunar rover mission,” Astronomy, 28 October 2022: https://astronomy.com/news/2022/10/united-arab-emirates-expands-lunar-plans-with-chinese-collaboration

- Christopher McFadden, “US restricts UAE’s ‘Rashid 2’ from boarding China’s mission to Moon,” Interesting Engineering, 24 Match 2023: https://interestingengineering.com/science/uae-rashid-2-mission-to-moon

Video

- “UAE Space Mission: Rashid Rover is due to land on the moon around April 2023 | Latest News | WION,” posted by WION, 17 December 2022: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=olWgwrlb7mk