Peter Lobner, 10 May 2023

1. Introduction

On 9 May 2023, Lockheed Martin announced that its hybrid airship business, including intellectual property and related assets, had been transitioned to a newly formed, commercial company called AT2 Aerospace. The Lockheed Martin press release reported, “AT2 Aerospace, based in Santa Clarita, California, is extending our work to bring hybrid airships to fruition. The AT2 team is developing airship solutions to support commercial and humanitarian applications around the world. Dr. Robert Boyd, retired Lockheed Martin Hybrid Airship program manager, is president and chief operating officer of AT2 Aerospace.”

The AT2 website is here: www.at2aero.space

2. Background on Lockheed Martin’s hybrid airship program

Since the 1980s, Lockheed Martin has been developing several different design approaches for semi-buoyant, hybrid airships with lifting body hulls. That work became focused in Lockheed Martin’s Advanced Development Programs (the Skunk Works) in Palmdale, CA, and produced an extensive series of patents related to large, hybrid airship design.

The only Lockheed Martin hybrid airship to fly was the P-791, which was a 120 foot (36.6 meter) long, tri-lobe, semi-buoyant hybrid airship that flew under a Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) sponsored Project WALRUS Phase 1 contract, and also served as a sub-scale technology demonstrator for future Lockheed Martin heavy-lift hybrid airships. The first flight of the P-791 took place on 31 January 2006 at Lockheed Martin’s facility in Palmdale. Airship magazine reported that the P-791 flew six times. Lockheed Martin claimed that all flight test objectives were successfully met and there were no subsequent flight tests.

Lockheed Martin P-791. Source: Lockheed Martin (2006)

In March 2011, Lockheed Martin announced that it planned to develop a larger commercial version of the P-791, to be called SkyTug, which would be a scaled up hybrid airship designed to carry at least 20 tons of cargo. A trademark application for the term “SkyTug” was filed on 25 August 2011.

By 2013, reference to SkyTug had disappeared and Lockheed Martin was promoting the LMH-1 as their next large commercial hybrid airship based on the P-791 design.

General arrangement of the LMH-1 hybrid airship. Source: Lockheed Martin

Rendering, LMH-1 bow quarter view. Source: Lockheed Martin via BBC (November 2019)

On March 12, 2012 the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) announced that Lockheed Martin Aeronautics submitted an application for type certification for the model LMZ1M (LMH-1), which is “a manned cargo lifting hybrid airship incorporating a number of advanced features.” The FAA assigned docket number FAA-2013-0550 to that application.

To address the gap in airship regulations head-on, Lockheed Martin submitted to the FAA their recommended criteria document, “Hybrid Certification Criteria (HCC) for Transport Category Hybrid Airships,” which is a 206 page document developed specifically for the LMZ1M (LMH-1). The HCC is also known as Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Company Document Number 1008D0122, Rev. C, dated 31 January 2013. You can download the HCC document and related public docketed items from the FAA website here:

https://www.regulations.gov/docket/FAA-2013-0550/document

In November 2015, the FAA’s Seattle Aircraft Certification Office approved Lockheed’s project-specific certification plan for the LMZ1M (LMH-1). In a 17 November 2015 press release, Lockheed Martin announced:

“Given that Hybrid Airships did not fit within existing FAA regulations, the team worked to create a new set of criteria allowing non rigid hybrid airships to safely operate in a commercial capacity. Transport Canada was also involved in the development of this criteria to ensure it included safety concerns unique to Canada.”

“Lockheed Martin and the FAA have been working together for more than a decade to define the criteria to certify Hybrid Airships for the Transport Category. This criteria was approved by the FAA in April 2013. Following that approval, the team has been developing the project specific certification plan over the past two years, which details how it will accomplish everything outlined in the Hybrid Certification Criteria.”

“Earlier this year Lockheed Martin along with Hybrid Enterprises LLC kicked off sales for the 20 ton variety of the Hybrid Airship. They are on track to deliver operational airships as early as 2018.”

No new documentation was subsequently added to the public webpage for docket FAA-2013-0550, so there was no public visibility of the type certification effort.

In September 2017, Lockheed Martin reported it had Letters of Intent (LOIs) for 24 LMH-1 hybrid airships, with their largest customer being Straightline Aviation (https://www.straightlineaviation.com), which had signed an LOI for 12 LMH-1s. At that time, the first “float out” of the LMZ1M (LMH-1) had slipped to 2019. As of May 2023, the airship has not yet been “floated out”.

On 9 May 2023, Lockheed Martin reported, “For some time, we have been in search of a transition partner to continue development of this important commercial work.” That “transition partner” is the newly formed, commercial company AT2 Aerospace.

3. The AT2 Aerospace Z1 Hybrid Airship

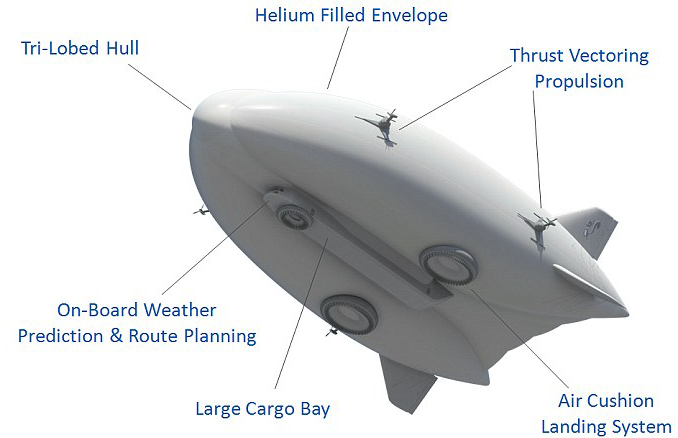

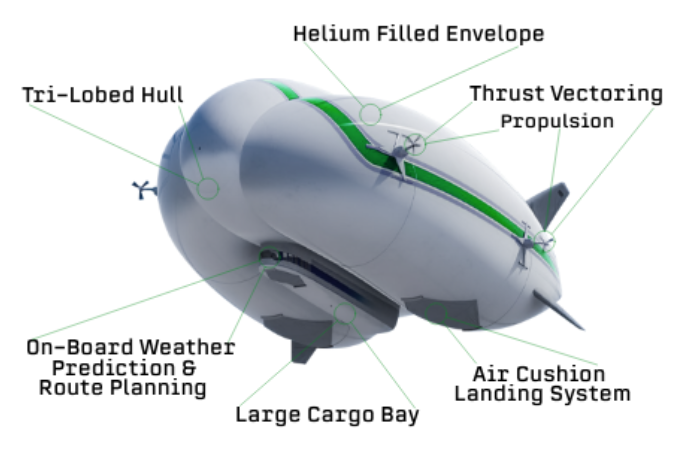

As portrayed on the AT2 Aerospace website, their Z1 hybrid airship appears to be the current incarnation of the former Lockheed Martin LMH-1. AT2 Aerospace summarizes the main attributes of their Z1 hybrid airship as follows:

“AT2 Aerospace’s revolutionary hybrid airship is the future of aviation technology. Capable of operating in the most remote and inaccessible locations, this innovative aircraft offers a cost-effective solution for heavy cargo transpiration while minimizing environmental and social impact.”

- “The Z1’s unique Air Cushion Landing System (ACLS) allows the Z1 to land and takeoff from almost any location on the planet.

- The Z1 utilizes buoyant lift technology delivering exceptional fuel efficiency, minimizing carbon emissions, and ultimately reducing transportation costs.

- The Z1 will connect emerging economies to global trade networks.

- The Z1 moves cargo faster than sea and land transportation at a fraction of the cost of existing cargo aircraft, filling a major gap in the global transportation market from a speed vs. cost perspective.”

AT2 Aerospace also identified the following attributes:

- Simple controls minimize human error

- Large volume cargo bays, larger payloads

- Safer in icing effects

- Quiet: Ideal for noise sensitive locations

AT2 Aerospace expects that their Z1 hybrid airship will “open the entire world to commerce, humanitarian aid and exploration with affordable and reliable operations.”

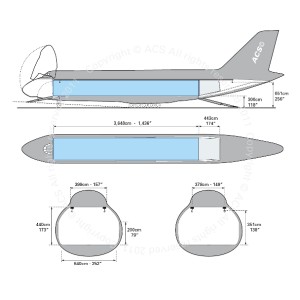

General arrangement of the Z1 hybrid airship. Source: AT2 Aerospace

The near-term challenge for AT2 Aerospace will be to get clarity from the FAA on the actions remaining, and the approximate time scale, to conclude the first-ever type certification process for a hybrid airship in the U.S. With a type certificate in hand, the Z1 can be put to the test by a few early-adopters in what hopefully will become an emerging worldwide commercial airship market.

4. For more information

- “Hybrid Airship Enters The Transfer Portal,” Lockheed Martin press release, 9 May 2023: https://news.lockheedmartin.com/2023-05-09-Hybrid-Airship-Enters-the-Transfer-Portal

- “Lockheed Martin Forms New Company Around Hybrid Airship Efforts,” Manufacturing Net, 10 May 2023: https://www.manufacturing.net/aerospace/news/22861518/lockheed-martin-forms-new-company-around-hybrid-airship-efforts

- Peter Lobner, Modern Airships – Part 1: https://lynceans.org/all-posts/modern-airships-part-1/

- Lockheed Martin – Rigid hybrid airships: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Lockheed-Martin_Ultra-large-rigid-hybrid-airships.pdf

- Lockheed Martin – Aerocraft semi-rigid hybrid airship: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Lockheed-Martin_Aerocraft-.pdf

- Lockheed Martin – P-791 hybrid airship: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Lockheed-Martin_P791.pdf

- Lockheed Martin – SkyTug and LMH-1 hybrid airships: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Lockheed-Martin_SkyTug-LMH-1.pdf

- DARPA Project WALRUS: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/DARPA_Project-WALRUS.pdf