Peter Lobner, 1 February 2021

This article provides a brief overview of the “mainstream” international plans to deliver the first large tokamak commercial fusion power plant prototype in the 2060 to 2070 timeframe. Then we’ll take a look at alternate plans that could lead to smaller and less expensive commercial fusion power plants being deployed much sooner, perhaps in the 2030s. These alternate plans are enabled by recent technical advances and a combination of public and private funding for many creative teams that are developing and testing a diverse range of fusion machines that may be developed in the near-term into compact, relatively low-cost fusion power plants.

This article includes links in Section 6 to a set of supporting articles that provide details on 18 fusion power reactor development projects, mostly at private firms. You can download a pdf copy of this main article here: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/The-Fork-in-the-Road-to-Electric-Power-From-Fusion-converted_1.pdf

1. Plodding down the long road to controlled nuclear fusion with ITER

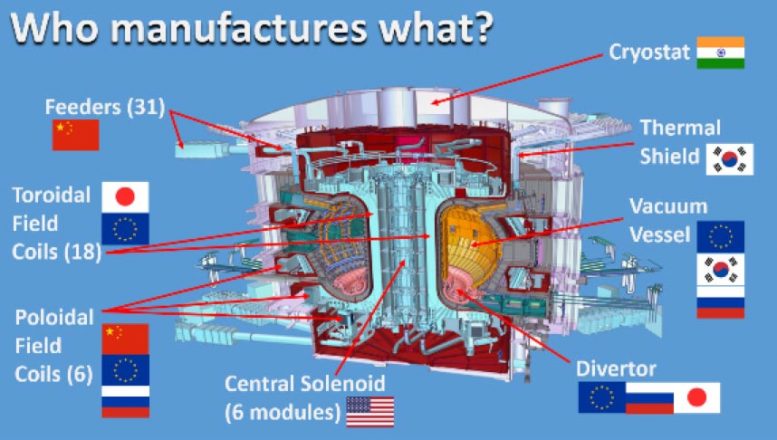

Mainstream fusion development is focused on the construction of the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), which is a very large magnetic confinement fusion machine. The 35-nation ITER program describes their reactor as follows: “Conceived as the last experimental step to prove the feasibility of fusion as a large-scale and carbon-free source of energy, ITER will be the world’s largest tokamak, with ten times the plasma volume of the largest tokamak operating today.” ITER is intended “to advance fusion science and technology to the point where demonstration fusion power plants can be designed.”

ITER is intended to be the first fusion experiment to produce a net energy gain (“Q”) from fusion. Energy gain is the ratio of the amount of fusion energy produced (Pfusion) to the amount of input energy needed to create the fusion reaction (Pinput). In its simplest form, “breakeven” occurs when Pfusion = Pinput and Q = 1.0. The highest value of Q achieved to date is 0.67, by the Joint European Torus (JET) tokamak in 1997.The ITER program was formally started with the ITER Agreement, which was signed on 21 November 2006.

components. Source: SciTechDaily (28 Jul 2020)

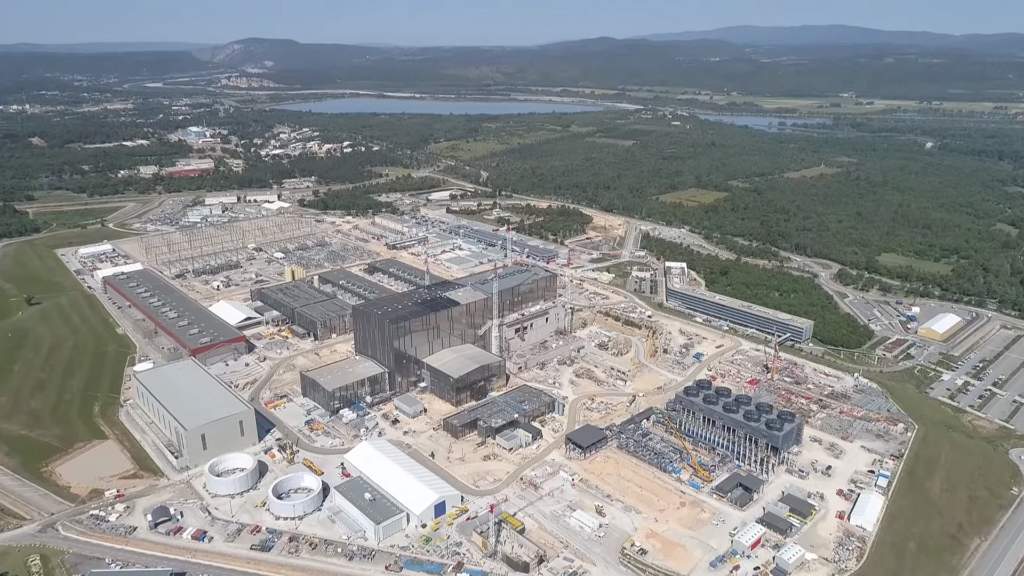

The official start of the “assembly phase” of the ITER reactor began on 28 July 2020. The target date of “first plasma” currently is in Q4, 2025. At that time, the reactor will be only partially complete. During the following ten years, construction of the reactor internals and other systems will be completed along with a comprehensive testing and commissioning program. The current goal is to start experiments with deuterium / deuterium-tritium (D/D-T) plasmas in December 2035.

After initial experiments in early 2036, there will be a gradual transition to fusion power production over the next 12 – 15 months. By mid-2037, ITER may be ready to conduct initial high-power demonstrations, operating at several hundred megawatts of D-T fusion power for several tens of seconds. This milestone will be reached more than 30 years after the ITER Agreement was signed.

Subsequent experimental campaigns will be planned on a two-yearly cycle. The principal scientific mission goals of the ITER project are:

- Produce 500 MW of energy from fusion while using only 50 MW of energy for input heating, yielding Q ≥ 10

- Demonstrate Q ≥ 10 for burn durations of 300 – 500 seconds (5.0 – 8.3 minutes)

- Demonstrate long-pulse, non-inductive operation with Q ~ 5 for periods of up to 3,000 seconds (50 minutes).

All that energy will get absorbed in reactor structures, with some of it being carried off in cooling systems. However, ITER will not generate any electric power from fusion.

The total cost of the ITER program currently is estimated to be about $22.5 billion. In 2018, Reuters reported that the US had given about $1 billion to ITER so far, and was planning to contribute an additional $500 million through 2025. In Fiscal Year 2018 alone, the US contributed $122 million to the ITER project.

You’ll find more information on the ITER website, including a detailed timeline, at the following link: https://www.iter.org

2. Timeline for a commercial fusion power plant based on ITER

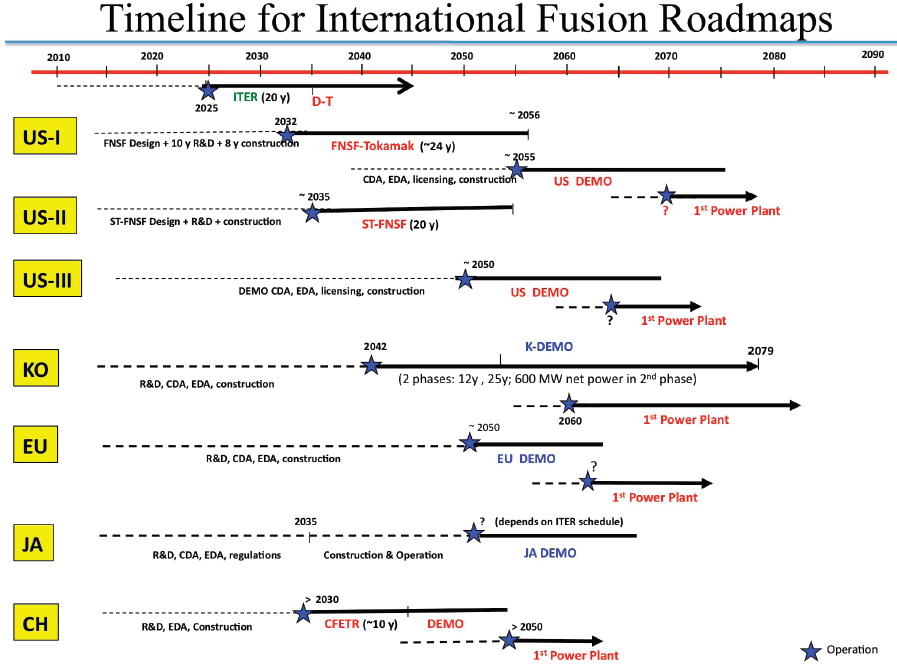

In December 2018, a National Academy of Sciences, Engineering & Medicine (NASEM) committee issued a report that included the following overview of timelines for fusion power deployment based on previously studied pathways for developing fusion power plants derived from ITER. The timelines for the USA, South Korea, Europe, Japan and China are shown below.

Plasma Research” (NASEM, 2019)

All of the pathways include plans for a DEMO fusion power plant (i.e., a prototype with a power conversion system) that would start operation between 2050 and 2060. Based on experience with DEMO, the first commercial fusion power plants would be built a decade or more later. You can see that, in most cases, the first commercial fusion power plant is not projected to begin operation until the 2060 to 2070 timeframe.

3. DOE is helping to build a fork in the road

Fortunately, a large magnetic confinement tokamak like ITER is not the only route to commercial fusion power. However, ITER currently is consuming a great deal of available resources while the promise of fusion power from an ITER-derived power plant remains an elusive 30 years or more away, and likely at a cost that will not be commercially viable.

Since the commitment was made in the early 2000s to build ITER, there have been tremendous advances in power electronics and advanced magnet technologies, particularly in a class of high temperature superconducting (HTS) magnets known as rare-earth barium copper oxide (REBCO) magnets that can operate at about 90 °K (-297 °F), which is above the temperature of liquid nitrogen (77 °K; −320 °F). These technical advances contribute to making ITER obsolete as a path to fusion power generation.

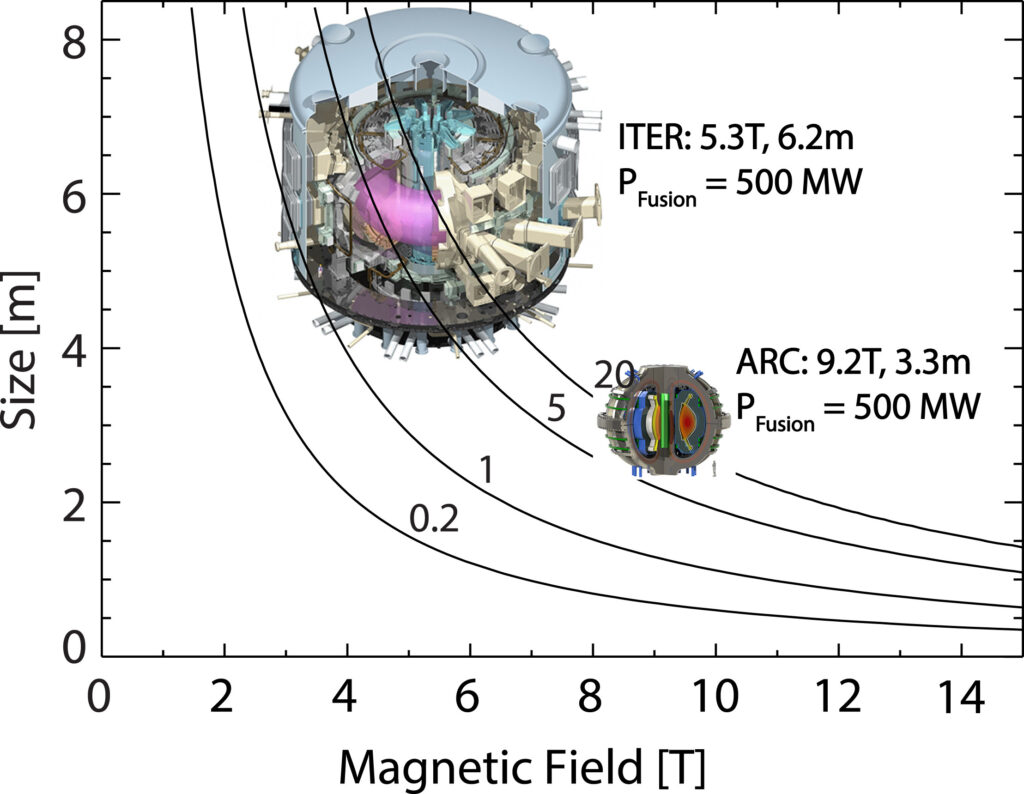

A 2019 paper by Martin Greenwald describes the relationship of constant fusion gain (Q = Pfusion / Pinput) to the magnetic field strength (B) and the plasma radius (R) of a tokamak device. As it turns out, Q is proportional to the product of B and R, so, for a constant gain, there is a tradeoff between the magnetic field strength and the size of the fusion device. This can be seen in the comparison between the relative field strengths and sizes of ITER and ARC (a tokomak being designed now), which are drawn to scale in the following chart.

Contours of constant fusion gain (Q) plotted against magnetic field strength (T, Tesla) and device size (plasma radius in meters): Source: Greenwald (2019)

ITER has lower field strength conventional superconducting magnets and is much larger than ARC, which has much higher field strength HTS magnets that enable its compact design. Greenwald explains, “With conventional superconductors, the region of the figure above 6T was inaccessible; thus, ITER, with its older magnet technology, is as small as it could be.” So, ITER will be a big white elephant, useful for scientific research, but likely much less useful on the path to fusion power generation than anyone expected when they signed the ITER Agreement in 2006.

For the past decade, there has been increasing interest in, and funding for, developing lower cost, compact fusion power plants using any fusion technology that can deliver a useful power generation capability at an commercially viable cost. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Advanced Research Project Agency – Energy (ARPA-E) has recommended the following cost targets for such a commercial fusion power plant:

Overnight capital cost of < US $2 billion and < $5/W

At $5/W, the upper limit would be a 400 MWe fusion power plant.

Since 2014, DOE has created a series of funding programs for fusion R&D projects to support development of a broad range of compact, low-cost fusion power plant design concepts. This was a significant change for the DOE fusion program, which has been contributing to ITER and a whole range of other fusion-related projects, but without a sense of urgency for delivering the technology needed to develop and operate commercial fusion power plants any time soon. Now, a small part of the DOE fusion budget is focused on resolving some of the technical challenges and de-risking the path forward sooner rather than later, and thereby improving the investment climate to the point that investors become willing to contribute to the development of small, low-cost fusion power plants that may be able to produce electrical power within the next decade or two.

These DOE R&D programs are administered ARPA-E and the Office of Science, Fusion Energy Sciences (FES).

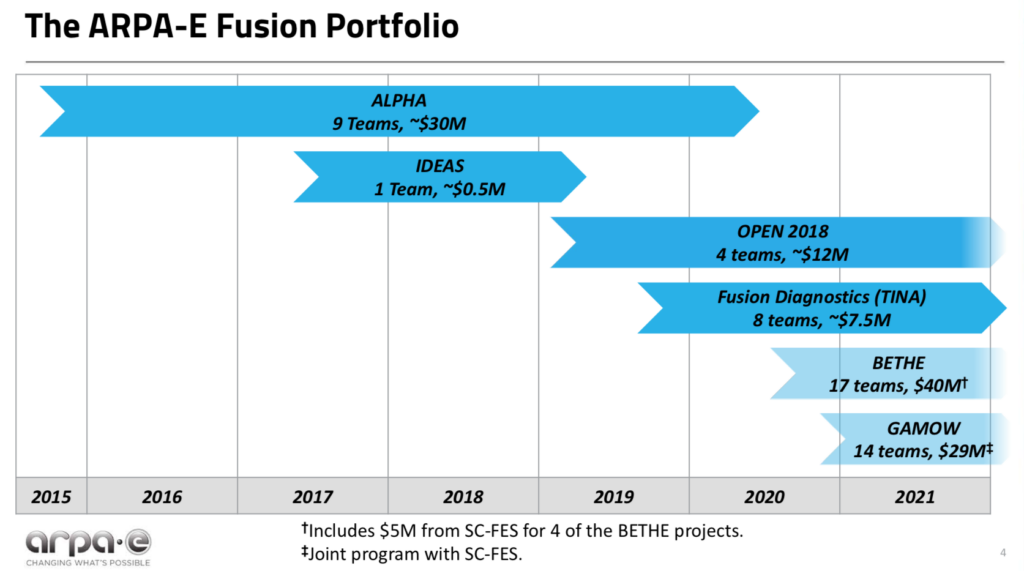

- ARPA-E advances high-potential, high-impact energy technologies that are too early for private-sector investment. The ARPA-E fusion R&D programs are named ALPHA, IDEAS, BETHE, TINA and GAMOW. ARPA-E jointly funds the GAMOW fusion R&D program and part of the BETHE program with FES. In addition, the ARPA-E OPEN program makes R&D investments in the entire spectrum of energy technologies, including fusion.

- FES is the largest US federal government supporter of research that is addressing the remaining obstacles to commercial fusion power. The FES fusion R&D program is named INFUSE. In addition FES jointly funds GAMOW and part of BETHE with ARPA-E.

Here’s an overview of these DOE programs.

DOE ARPA-E ALPHA program (2015 – 2020)

In 2015, ARPA-E initiated a five-year, $30 million research program into lower-cost approaches to producing electric power from fusion. This was known as the ALPHA program (Accelerating Low-Cost Plasma Heating and Assembly). The goal was to expand the range of potential technical solutions for generating power from fusion, focusing on small, low-cost, pulsed magneto-inertial fusion (MIF) devices.

The ARPA-E ALPHA program home page is here: https://arpa-e.energy.gov/technologies/programs/alpha

There were nine program participants in the ALPHA program. Helion Energy ($3.97 million) and MIFTI ($4.60 million) were among the private fusion reactor firms receiving ALPHA awards. Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) received $6.63 million to fund the Plasma Liner Experiment (PLX-α) team, which included the private firm HyperV Technologies Corp.

In 2018, ARPA-E asked JASON to assess its accomplishments on the ALPHA program and the potential of further investments in this field. Among their findings, JASON reported that MIF is a physically plausible approach to controlled fusion and, in spite of very modest funding to date, some particular approaches are within a factor of 10 of scientific break-even. JASON also recommended supporting all promising approaches, while giving near-term priority to achieving breakeven (Q ≥ 1) in a system that can be scaled up to be commercial power plant. You can read the November 2018 JASON report here: https://fas.org/irp/agency/dod/jason/fusiondev.pdf

DOE ARPA-E IDEAS program (2017 – 2019)

The ARPA-E IDEAS program (Innovative Development in Energy-Related Applied Science) provides support of early-stage applied research to explore pioneering new concepts with the potential for transformational and disruptive changes in any energy technology. IDEAS awards are restricted to a maximum of $500,000 in funding. There have been 59 IDEAS awards for a broad range of energy-related technologies, largely to national laboratories and universities.

The IDEAS program home page is here: https://arpa-e.energy.gov/technologies/programs/ideas

There was one fusion-related IDEAS award to the University of Washington ($482 k).

DOE ARPA-E OPEN program (2018)

In 2018, ARPA-E issued its fourth OPEN funding opportunity designed to catalyze transformational breakthroughs across the entire spectrum of energy technologies, including fusion. OPEN 2018 is a $199 million program funding 77 projects.

The OPEN 2018 program home page is here: https://arpa-e.energy.gov/technologies/open-programs/open-2018

Four fusion-related projects were funded for a total of about $12 million. ZAP Energy ($6.77 million), CTFusion ($3.0 million) and Princeton Fusion Systems ($1.1 million) were among the private fusion reactor firms receiving OPEN 2018 awards.

DOE ARPA-E TINA Fusion Diagnostics program (2019 – 2021)

The TINA program established diagnostic “capability teams” to support state-of-the-art diagnostic system construction/deployment and data analysis/interpretation on ARPA-E-supported fusion experiments. This program awarded $7.5 million to eight teams, primarily from national laboratories and universities.

DOE ARPA-E BETHE program (2020 – 2024)

DOE’s ARPA-E also runs the BETHE program (Breakthroughs Enabling THermonuclear-fusion Energy), which is a $40 million program that aims to deliver a large number of lower-cost fusion concepts at higher performance levels. BETHE R&D is focused in the following areas:

- Concept development to advance the performance of inherently lower cost but less mature fusion concepts.

- Component technology development that could significantly reduce the capital cost of higher cost, more mature fusion concepts.

- Capability teams to improve/adapt and apply existing capabilities (e.g., theory/modeling, machine learning, or engineering design/fabrication) to accelerate the development of multiple concepts.

FES contributes $5 million to BETHE program funding for component technology development. The BETHE program home page is here: https://arpa-e.energy.gov/technologies/programs/bethe

Sixteen research projects were awarded on 7 April 2020. Brief project descriptions are available here: https://arpa-e.energy.gov/sites/default/files/documents/files/BETHE_Project_Descriptions_FINAL.24.20.pdf

ZAP Energy ($1 million) and Commonwealth Fusion Systems ($2.39 million) were among the private fusion reactor firms directly receiving BETHE awards.

The following awards were made to universities or national laboratories working with teams that include a significant role for a private fusion reactor firm:

- University of Washington received $1.5 million for improving IDCD plasma control, which is applicable to their collaborative work with CTFusion on the Dynomak fusion reactor concept.

- LANL received $4.62 million to fund the Plasma Liner Experiment (PLX-α) team, which includes HyperJet

DOE ARPA-E / FES GAMOW program (2020 – 2024)

Yet another DOE funding program for fusion research is named GAMOW (Galvanizing Advances in Market-Aligned Fusion for an Overabundance of Watts), which is a $29 million program announced in February 2020. GAMOW is jointly funded and overseen by ARPA-E and FES. GAMOW program focuses on the following three areas:

- Technologies and subsystems between the fusion plasma and balance of plant.

- Cost-effective, high-efficiency, high-duty-cycle driver technologies.

- Crosscutting areas such as novel fusion materials and advanced in additive manufacturing for fusion-relevant materials and components.

The GAMOW program home page is here: https://arpa-e.energy.gov/technologies/programs/gamow

In September 2020, ARPA-E announced 14 projects, primarily for national laboratory and university participants that were funded under the GAMOW program. Brief project descriptions are available here: https://arpa-e.energy.gov/sites/default/files/documents/files/GAMOW_Project_Descriptions_FINAL_9.2.20.pdf

Princeton Fusion Systems ($1.1 million) was among the private fusion reactor firms receiving GAMOW awards.

DOE FES INFUSE program (2020 – present)

The DOE FES INFUSE program (Innovation Network for Fusion Energy) was created to “accelerate fusion energy development in the private sector by reducing impediments to collaboration involving the expertise and unique resources available at DOE laboratories.” ….”DOE-FES will accept basic research applications focused on innovation that support production and utilization of fusion energy (e.g., for generation of electricity, supply of process heat, etc.)….”

In Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021, the INFUSE program annual budget was $4 million. INFUSE is a cost sharing program with DOE-FES funding 80% of a project’s cost and the award recipient funding the remaining 20%. The DOE-FES INFUSE program home page is here: https://infuse.ornl.gov

So far, there have been three rounds of INFUSE awards. I think you will find that it is much more difficult to find detailed information on the DOE FES INFUSE awards, which are administered by Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), than it is to find information on any of the DOE ARPA-E program. Here’s a brief INFUSE summary.

- 1st round FY 2020: On 15 October 2019, DOE announced the first INFUSE awards, which provided funding for 12 projects with representation from six private companies partnering with six national laboratories. The six private firms included: Commonwealth Fusion Systems (4 awards) and TAE Technologies, Inc. (3 awards)

- 2nd round FY 2020: On 3 September 2020, DOE announced funding for 10 projects. The private firms included: Commonwealth Fusion Systems (3 awards), TAE Technologies, Inc. (1 award), Tokamak Energy, Inc. (UK, 3 awards), and General Fusion Corp. (Canada, 1 award).

- 1st round FY 2021: On 3 December 2020, DOE announced funding 10 projects in a second round of FY 2021 INFUSE awards. The private firms receiving awards included: Commonwealth Fusion Systems (1 award), General Fusion Corp. (Canada, 1 award), MIFTI (1 award), Princeton Fusion Systems (1 award), TAE Technologies, Inc. (2 awards), Tokamak Energy, Inc. (UK, 2 awards).

DOE-FES has issued a call for new proposals for FY 2021 INFUSE awards. The closing date for submissions is 26 February 2021.

DOE SBIR and STTR programs

The DOE Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs develop innovative techniques, instrumentation, and concepts that have applications to industries in the private sector, including in the fusion sector. The SBIR / STTR home page is here: https://www.energy.gov/science/sbir/small-business-innovation-research-and-small-business-technology-transfer

Fusion-related awards are listed here: https://science.osti.gov/sbir/Research-Areas-and-Impact#FES

The DOE grand total

So far, these ARPA-E and FES programs have committed about $127 million in public funds to 77 different projects between 2014 and 2021. While some of the awards are sizeable ($5 – 6 million), many are very modest awards. The DOE total for all small (non-mainstream) fusion projects over a seven year period is about the same amount as the annual US contribution to the ITER program, which isn’t going lead to a fusion power plant in my lifetime, if ever.

While DOE has been kind enough to create the fork in the road, they do not have the deployable financial resources to push on to the next step of actually building prototypes of commercial fusion power plants in the near term.

4. A roadmap for achieving commercial fusion sooner

In 2019 and 2021, the National Academies and DOE-FES, respectively, published the recommendations of committees that were charged with defining the path(s) forward for the US to achieve commercial fusion power. In both cases, the committee recommended continued support for ITER while urging the US to proceed with a separate national program that encourages and supports public-private partnerships to build compact power plants that produce electricity from fusion at the lowest possible capital cost. These committee reports are briefly summarized below.

National Academies: “Final Report of the Committee on a Strategic Plan for U.S. Burning Plasma Research” (2019)

In December 2018, a National Academy of Sciences, Engineering & Medicine (NASEM) committee issued a report entitled, “A Strategic Plan for U.S. Burning Plasma Research.”

As noted previously, the NASEM report described the current path forward based on power plants derived largely from ITER technology. On this path, the first commercial fusion power plant is not projected to begin operation until the 2060 to 2070 timeframe.

The NASEM committee report is very important because it defines an alternate pathway (i.e., the fork in the road) that could deliver fusion power considerably sooner and at much lower capital cost.

The committee offered the following recommendations:

- The US should remain an ITER partner. This is the most cost-effective way to gain experience with burning plasma at the scale of a power plant. However:

- Significant R&D is required in addition to ITER to produce electricity from this type of fusion reactor.

- ITER is too large and expensive to be economically competitive in the US market when compared to other carbon-neutral energy technologies.

- The US should start a national program of accompanying research and technology leading to the construction of a compact pilot power plant that produces electricity from fusion at the lowest possible capital cost.

- Emphasize developing innovative, world-leading solutions.

- Effective application of US near-term R&D investments is critical, as other nations continue to invest in new fusion facilities that advance their own approaches.

You can read the NASEM report here: https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/a-strategic-plan-for-us-burning-plasma-research

DOE FES: “Powering the Future – Fusion & Plasmas” (2021)

In January 2021, DOE FES published a draft report from their Fusion Energy Sciences Advisory Committee (FESAC) entitled “Powering the Future – Fusion & Plasmas.” This draft report supports the NASEM committee recommendations and concluded that there are two viable paths to commercial fusion power:

- Partnership in the ITER fusion project is essential for US fusion energy development, as is supporting the continued growth of the private sector fusion energy industry.

- Public-private partnerships have the potential to reduce the time required to achieve commercially viable fusion energy.

- The fusion pilot plant goal requires “a pivot toward research and development of fusion materials and other needed technology.” Several new experimental facilities were recommended.

You can read the complete draft FESAC report here: https://science.osti.gov/-/media/fes/fesac/pdf/2020/202012/DRAFT_Fusion_and_Plasmas_Report_120420.pdf

As of late January 2021, the FESAC final report was in preparation. When available, it will be posted here: http://usfusionandplasmas.org

Funding at the fork in the road

At the fork in the road, the US will be hedging its bets and taking both paths, continuing to support ITER at the current level (about $125 million/year) while building new fusion experimental facilities and trying to place a stronger emphasis on timely development of compact fusion power plants through public-private partnerships as well as infusions of private capital.

In the years ahead, the DOE FES fusion budget is expected to be essentially flat, with growth at just a modest rate of 2%/year being among the likely range of budget scenarios. At the same time, FES will attempt to launch several new major fusion R&D facilities and related programs, as recommended by FESAC.

Without a significantly bigger budget authorization from Congress, the FES budget becomes a zero sum game. To create the budget for any of these new R&D facilities and programs, other part of the FES budget have to lose. In this constrained budget environment, I think FES funding for compact fusion power plant development will find stiff competition and will not be on a growth path.

Recall that ARPA-E’s role is to advance high-potential, high-impact energy technologies that are too early for private-sector investment. When major risk issues for a particular fusion reactor concept have been resolved to an appropriate level, funding from ARPA-E may be redirected to other higher risk matters waiting to be addressed.

While the NASEM and FESAC reports support public-private partnerships, the sheer magnitude of the funds required (many billions of dollars) to develop several small prototype fusion power plant designs in parallel exceeds DOE’s ability to fund the deals at the same level as the current 80% (DOE) / 20% (private) partnership deals. The FES annual budget for the past three years has been quite modest: $564 million (FY2019 enacted), $671 million (FY2020 enacted) and $425 million (FY2021 requested).

Making real progress toward deployment of operational fusion power plants will depend on billions of dollars in private / institutional capital being invested in the firms that will design and build the first small commercial fusion power plants.

I think DOE and the commercial fusion power industry are in a similar position to NASA and the commercial spaceflight industry two decades ago when Blue Origin (Jeff Bezos, 2000) and SpaceX (Elon Musk, 2002) were founded. At that time, the traditional route to space was via NASA. Two decades later, it’s clear that many commercial firms and their investors have contributed to building a robust low Earth orbit spaceflight industry that could never have been developed in that short time frame with NASA’s limited budget. In the next two decades, I think the same type of transition needs to occur in the relationship between DOE and the private sector fusion industry if we expect to reap the benefits of clean fusion power soon. It’s time for FES and the commercial fusion industry to confirm that they share a vision and a common aggressive timeline for bringing small commercial fusion power plants to the market. That point doesn’t come across in the FESAC report.

Private and institutional investors already making major investments in the emerging fusion energy market. As you might expect, some fusion firms have been much more successful than others in raising funds. You’ll find a summary of publically available funding information on the Fusion Energy Base website here: https://www.fusionenergybase.com/organization/commonwealth-fusion-systems

5. The US Navy also may be building a fork in the road

The Navy has been quietly developing its own concepts for compact fusion power plants. We’ll take a look at three recent designs. Could the Navy wind up being an important contributor to the development and deployment of commercial fusion power plants?

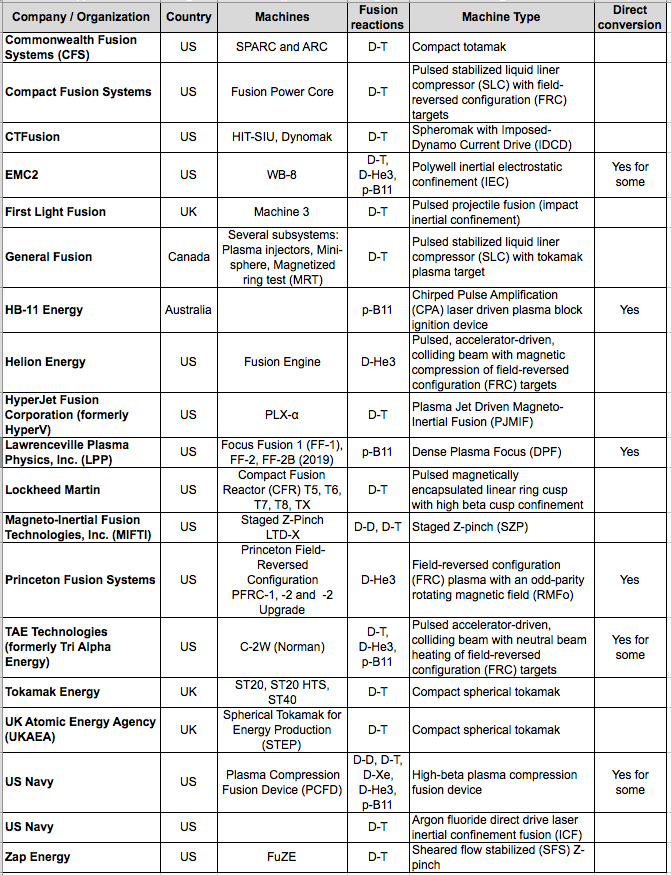

6. The race is on to beat ITER with smaller, lower-cost fusion

In this section, we’ll take a look at the status of the following small fusion power plant development efforts, mostly by private companies.

Collectively, they are applying a diverse range of technologies to the challenge of generating useful electric power from fusion at a fraction of the cost of ITER. Based on claims from the development teams, it appears that some of the compact fusion reactor designs are quite advanced and probably will be able to demonstrate a net energy gain (Q > 1.0) in the 2020s, well before ITER.

You’ll find details on these 18 organizations and their fusion reactor concepts in my separate articles at the following links:

- Commonwealth Fusion Systems: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Commonwealth-Fusion-Systems_US-converted.pdf

- Compact Fusion Systems: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Compact-Fusion-Systems_US-converted.pdf

- CTFusion: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/CTFusion_US-converted.pdf

- EMC2: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/EMC2_US-converted.pdf

- First Light Fusion: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/First-Light-Fusion_UK-converted.pdf

- General Fusion: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/General-Fusion_Canada-converted.pdf

- HB-11 Energy: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/HB11-Energy_Australia-converted.pdf

- Helion Energy: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Helion-Energy_US-converted.pdf

- HyperJet Fusion Corporation (formerly HyperV): https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/HyperJet-Fusion_US-converted.pdf

- Lawrenceville Plasma Physics, Inc. (LPP): https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/LPP-Fusion_US-converted.pdf

- Lockheed Martin: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Lockheed-Martin-CFR_US-converted.pdf

- Magneto-Inertial Fusion Technologies, Inc. (MIFTI): https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/MIFTI_US-converted.pdf

- Princeton Fusion Systems: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Princeton-Fusion-Systems_US-converted.pdf

- TAE Technologies (formerly Tri Alpha Energy): https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/TAE-Technologies_US-converted.pdf

- Tokamak Energy Ltd.: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Tokamak-Energy_UK-converted.pdf

- UK Atomic Energy Agency STEP: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/STEP_UK-converted.pdf

- US Navy: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/US-Navy-converted.pdf

- Zap Energy: https://lynceans.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Zap-Energy_US-converted.pdf

7. Conclusions

There certainly are many different technical approaches being developed for small, lower-cost fusion power plants. Several teams are reporting encouraging performance gains that suggest that their particular solutions are on credible paths toward a fusion power plant. However, as of January 2021, none of the operating fusion machines have achieved breakeven, with Q = 1.0, or better. It appears that goal remains at least a few years in the future, even for the most advanced contenders.

The rise of private funding and public-private partnerships is rapidly improving the resources available to many of the contenders. Good funding should spur progress for many of the teams. However, don’t be surprised if one or more teams wind up at a technical or economic dead end that would not lead to a commercially viable fusion power plant. Yes, I think ITER is heading down one of those dead ends right now.

So, where does that leave us? The promise for success with a small, lower-cost fusion power plant is out there, and such power plants should win the race by a decade or more over an ITER-derived fusion power plant. While there are many contenders, which ones are the leading contenders for deploying a commercially viable fusion power plant?

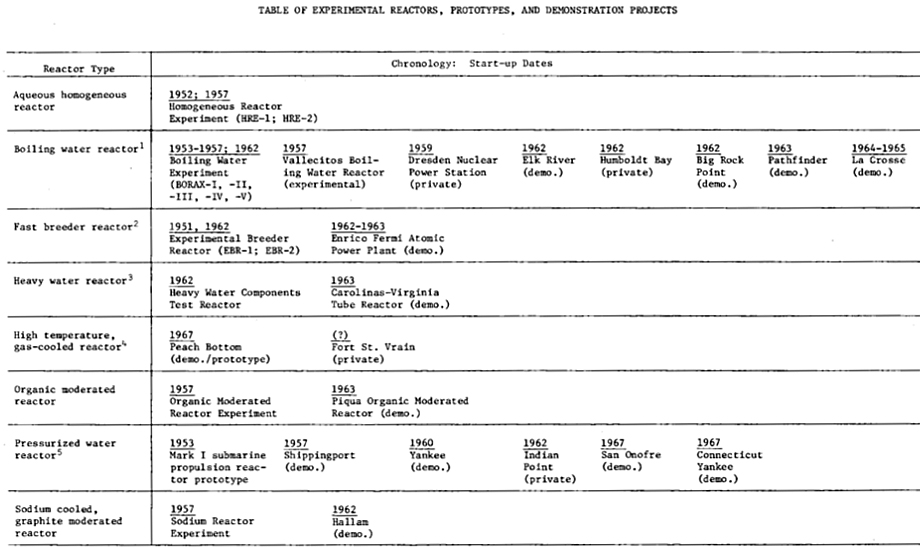

To give some perspective, it’s worth taking a moment to recall the earliest history of the US commercial nuclear power industry, which is recounted in detail for the period from 1946 – 1963 by Wendy Allen in a 1977 RAND report and summarized in the following table.

The main points to recognize from the RAND report are:

- Eight different types of fission reactors were built as demonstration plants and tested. All of the early reactors were quite small in comparison to later nuclear power plants.

- Some were built on Atomic Energy Commission (AEC, now DOE) national laboratory sites and operated as government-owned proof-of-principle reactors. The others were licensed by the AEC (now the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, NRC) and operated by commercial electric power utility companies. These reactors were important for building the national nuclear regulatory framework and the technical competencies in the commercial nuclear power and electric utility industries.

- In the long run, only two reactor designs survived the commercial test of time and proved their long-term financial viability: the pressurized water reactor (PWR) and the boiling water reactor (BWR), which are the most common types of fission power reactors operating in the world today.

See RAND report R-2116-NSF for more information of the early US commercial fission reactor demonstration plant programs here: https://www.rand.org/pubs/reports/R2116.html

With the great variety of candidate fusion power plant concepts being developed today, we simply don’t know which ones will be the winners in a long-term competition, except to say that an ITER-derived power plant will not be among the winners. What we need is a national demonstration plant program for small fusion reactors. This means we need the resources to build and operate several different fusion power reactor designs soon and expect that the early operating experience will quickly drive the evolution of the leading contenders toward mature designs that may be successful in the emerging worldwide market for fusion power. The early fission reactor history shows that we should expect that some of the early fusion power plant designs won’t survive in the long-term fusion power market, for a variety of reasons.

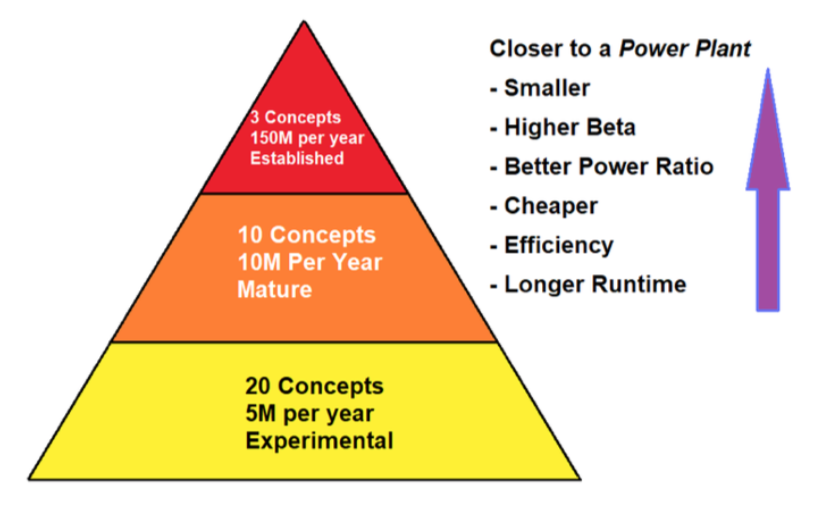

Matthew Moynihan, in his 2019 article, “Selling Fusion in Washington DC,” on The Fusion Podcast website, offered the following approach, borrowed from the biotech industry, to build a pipeline of credible projects while driving bigger investments into the more mature and more promising programs. Applying this approach to the current hodgepodge of DOE fusion spending would yield more focused spending of public money toward the goal of delivering small fusion power plants as soon as practical. The actual dollar amounts in the following chart can be worked out, but I think the basic principle is solid.

With this kind of focus from DOE, the many contenders in the race to build a small fusion power plant could be systematically ranked on several parameters that would make their respective technical and financial risks more understandable to everyone, especially potential investors. With an unbiased validation of relative risks from DOE, the leading candidates in the US fusion power industry should be able to raise the billions of dollars that will be needed to develop their designs into the first wave of demonstration fusion power plants, like the US fission power industry did 60 to 70 years ago.

Perhaps Carly Anderson had the right idea when she suggested Fantasy Fusion as a way to introduce some fun into the uncertain world of commercial fusion power development and investment. You can read her September 2020 article here: https://medium.com/prime-movers-lab/fantasy-fusion-77621cc901e2

If you believe we’re coming into the home stretch, it’s not too late to place a real bet by actually investing in your favorite fusion team(s). It is risky, but the commercial fusion power trophy will be quite a prize! I’m sure it will come with some pretty big bragging rights.

8. For more information

General

- “Nuclear Fusion – Global IP Landscape,” iRunway, 2016: https://arpa-e.energy.gov/sites/default/files/iRunway%20Research%20-%20Fusion%20Global%20Patent%20Landscape.pdf

- “Prospects for Low-Cost Fusion Development,” JSR-18-011, The MITRE Corporation, JASON Program Office, November 2018: https://fas.org/irp/agency/dod/jason/fusiondev.pdf

- Matthew Moynihan, “Selling Fusion in Washington DC,” The Fusion Podcast, 12 January 2019: https://www.thefusionpodcast.com/blog/2019/1/12/selling-fusion-in-washington-dc

- Martin Greenwald, “Fusion Energy: Research at the Crossroads,” Joule, 3, pp. 1172 – 1179, 15 May 2019: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2542435119301254

- Scott Hsu, “ARPA-E Fusion-Energy Programs and Plans,” ARPA-E, 2 October 2019: https://science.osti.gov/-/media/fes/fesac/pdf/2019/201910/Hsu.pdf

- “A Strategic Plan for U.S. Burning Plasma Research,” The National Academy of Sciences, Engineering & Medicine, 2019: https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/a-strategic-plan-for-us-burning-plasma-research

- “Powering the Future Fusion & Plasmas – A long-range plan to deliver fusion energy and to advance plasma science,” Fusion Energy Sciences Advisory Committee, DOE, 2020: https://science.osti.gov/-/media/fes/fesac/pdf/2020/202012/DRAFT_Fusion_and_Plasmas_Report_120420.pdf

- Laurence Hunt, “Compact Fusion Power Will Be Here Within 10-15 Years — So Now Is the Time To Plan for It!” Laurence Hunt’s Blog, 18 May 2020: http://laurencehunt.blogspot.com/2018/07/is-compact-fusion-power-now-fewer-that.html

- David Kramer, “Investments in privately funded fusion ventures grow,” Physics Today, 13 October 2020: https://physicstoday.scitation.org/do/10.1063/PT.6.2.20201013a/full/

- “Path to Economical Fusion,” ARPA-E: https://www.arpa-e.energy.gov/sites/default/files/documents/files/Economical_Fusion_Concepts_Report_Out.pdf

- Scott Hsu, “Discussion with the National Academies FPP Study Committee,” ARPA-E, 2 September 2020:

- Carly Anderson, “Fantasy Fusion,” medium, 4 September 2020: https://medium.com/prime-movers-lab/fantasy-fusion-77621cc901e2

- Bob Mumgaard, “Commercialization of fusion energy,” Commonwealth Fusion Systems, 26 September 2020: https://suli.pppl.gov/2020/course/Mumgaard_SULI_presentation.pdf

- Scott Hsu, “ARPA-E Updates & Overview of Fusion “Capability Teams,” ARPA-E, 2 December 2020: https://infuse.ornl.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Hsu_INFUSE.pdf

ITER

- “Fusion Energy Era: ITER Assembly Begins – World’s Largest Science Project to Replicate the Fusion Power of the Sun,” SciTechDaily, 28 July 2020: https://scitechdaily.com/fusion-energy-era-iter-assembly-begins/

- “ITER Research Plan within the Staged Approach (Level III – Provisional Version),” ITR-18-003, ITER Organization, 17 September 2018: https://www.iter.org/doc/www/content/com/Lists/ITER%20Technical%20Reports/Attachments/9/ITER-Research-Plan_final_ITR_FINAL-Cover_High-Res.pdf

DOE ALPHA Program

- “ARPA-E to Allow Grant Applications for Aneutronic Fusion Projects,” E-Cat World, 30 October 2014: https://e-catworld.com/2014/10/30/arpa-e-to-allow-grant-applications-for-aneutronic-fusion-projects-lppfusion/

- C. L. Nehi, et al., “Retrospective of the ARPA-E ALPHA Fusion Program,” Journal of Fusion Energy, 38_506 – 521, 2019: https://www.osti.gov/biblio/1572943

- And: https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1572943

DOE ARPA-E IDEAS program (2017 – 2019)

- “Stable Magnetized Target Fusion Plasmas,” University of Washington, 2017: https://arpa-e.energy.gov/technologies/projects/stable-magnetized-target-fusion-plasmas

DOE BETHE Program

- “Department of Energy Announces $30 Million for Fusion Energy R&D,” DOE ARPA-E (BETHE program), 7 November 2019: https://arpa-e.energy.gov/news-and-media/press-releases/department-energy-announces-30-million-fusion-energy-rd

- “Department of Energy Announces $32 Million for Lower-Cost Fusion Concepts,” DOE ARPA-E (BETHE program), 7 April 2020: https://arpa-e.energy.gov/news-and-media/press-releases/department-energy-announces-32-million-lower-cost-fusion-concepts

- “BETHE—Breakthroughs Enabling THermonuclear-fusion Energy – Project Descriptions,” ARPA-E, April 2020: https://arpa-e.energy.gov/sites/default/files/documents/files/BETHE_Project_Descriptions_FINAL.24.20.pdf

DOE GAMOW Program

- “Department of Energy Announces $30 Million for Commercial Fusion Energy R&D,” DOE ARPA-E & FES (GAMOW program), 13 February 2020: https://arpa-e.energy.gov/news-and-media/press-releases/department-energy-announces-30-million-commercial-fusion-energy-rd

- “Department of Energy Announces $29 Million in Fusion Energy Technology Development,” DOE ARPA-E & FES (GAMOW program), 2 September 2020: https://arpa-e.energy.gov/news-and-media/press-releases/department-energy-announces-29-million-fusion-energy-technology

- “GAMOW—Galvanizing Advances in Market-Aligned Fusion for an Overabundance of Watts – Project Descriptions,” September 2020: https://arpa-e.energy.gov/sites/default/files/documents/files/GAMOW_Project_Descriptions_FINAL_9.2.20.pdf

DOE INFUSE Program

- “Department of Energy Announces Private-Public Awards to Advance Fusion Energy Technology,” DOE Office of Science (INFUSE program), 15 October 2019: https://www.energy.gov/science/articles/department-energy-announces-private-public-awards-advance-fusion-energy-technology

- “Department of Energy Announces Next Round of Public-Private Partnership Awards to Advance Fusion Energy,” DOE Office of Science (INFUSE program), 3 September 2020: https://www.energy.gov/science/articles/department-energy-announces-next-round-public-private-partnership-awards-advance

- “Second round of 2020 public-private partnership awards announced by INFUSE fusion program,” Oak Ridge National Laboratory (INFUSE program), 3 December 2020: https://www.ornl.gov/news/second-round-2020-public-private-partnership-awards-announced-infuse-fusion-program

Arthur Ashkin. Source: laserfest.org

Arthur Ashkin. Source: laserfest.org

Gérard Mourou. Source: American Physical Society (APS). Donna Strickland. Source: University of Waterloo

Gérard Mourou. Source: American Physical Society (APS). Donna Strickland. Source: University of Waterloo