Peter Lobner

When 20th Century Fox approved the production of George Lucas’ first Star Wars movie, the studio had no special effects department and much of the technology eventually used in creating that movie did not exist. George Lucas founded ILM in the summer of 1975 to address this matter, and since then, ILM has been at the forefront of developing, innovating, and applying a broad range of new technologies that have been instrumental in the production of 317 movies and have fundamentally changed the course of the movie-making business.

You’ll find lots of interesting information at the ILM website:

You can read an excellent oral history, “The Untold Story of ILM, a Titan That Forever Changed Film,” by Alex French and Howie Kahn at the following link:

French and Kahn conclude:

“What defines ILM, however, isn’t a signature look, feel, or tone—those change project by project. Rather, it’s the indefatigable spirit of innovation that each of the 43 subjects interviewed for this oral history mentioned time and again. It is the Force that sustains the place.”

Pixar started in 1979 as an ILM internal project and it evolved into the premier computer animation studio, bringing us feature-length animated movies, including Toy Story, Monsters, Inc., Finding Nemo, Cars, A Bug’s Life and many more. More than being well-animated, the Pixar movies have excelled in telling meaningful stories through characters that have become part of our modern culture. You may recognize the Pixar logo shown below, with the little lamp, Luxo, Jr.:

Disney purchased Pixar in 2006, forming Walt Disney and Pixar Animation Studios. Pixar also is responsible for RenderMan software products that are widely used to manage texture, color, lighting and more in computer animation processes. Find out more at the Pixar website:

You can scroll through the Pixar timeline from 1979 to the present at the following link:

http://www.pixar.com/about/Our-Story

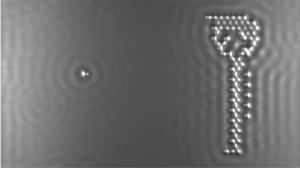

Movie special effects have come a very long way since Flash Gordon’s spaceship circled a landing site on visible wires, belching rocket exhaust that strangely resembled 4th of July sparklers.