Peter Lobner

On 7 September 2016, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reported that climate change increased the chance of record rains in Louisiana by at least 40%. This finding was based on a rapid assessment conducted by NOAA and partners after unusually severe and prolonged rains affected a broad area of Louisiana in August 2016. You can read this NOAA news release at the following link:

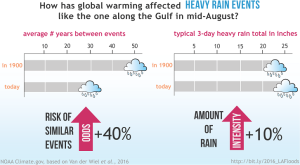

NOAA reported that models indicated the following:

- The return period for extreme rain events of the magnitude of the mid-August 2016 downpour in Louisiana has decreased from an average of 50 years to 30 years.

- A typical 30-year event in 1900 would have had 10% less rain than a similar event today; for example, 23 inches instead of 25 inches.

NOAA notes that “return intervals” are statistical averages over long periods of time, which means that it’s possible to have more than one “30-year event” in a 30-year period.

In their news release NOAA included the following aerial photos of Denham Springs, Louisiana. The photo on the left was at the height of the flooding on August 15, 2016. The photo on the right was taken three days later when floodwaters had receded.

Source: NOAA / National Geodetic Survey

Source: NOAA / National Geodetic Survey

World Weather Attribution (WWA) is an international effort that is, “designed to sharpen and accelerate the scientific community’s ability to analyze and communicate the possible influence of climate change on extreme-weather events such as storms, floods, heat waves and droughts”. Their website is at the following link:

https://wwa.climatecentral.org

WWA attempts to address the question: “Did climate change have anything to do with this?” but on their website, WWA cautions:

“Scientists are now able to answer this for many types of extremes. But the answer may vary depending on how the question is framed……..it is important for every extreme event attribution study to clearly define the event and state the framing of the attribution question.”

To get a feeling for how they applied this principal, you can read the WWA report, “Louisiana Downpours, August 2016,” at the following link:

https://wwa.climatecentral.org/analyses/louisiana-downpours-august-2016/

I find this report quite helpful in putting the Louisiana extreme precipitation event in perspective. I object to the reference to “human-caused climate change,” in the report because the findings should apply regardless of the source of the observed change in climate between 1900 and 2016.

On the WWA website, you can easily navigate to several other very interesting analyses of extreme weather events, and much more.

The National Academies Press (NAP) recently published the following two reports on extreme weather attribution, both of which are worth your attention.

The first NAP report, “Attribution of Extreme Weather Events in the Context of Climate Change,” applies to the type of rapid assessment performed by NOAA after the August 2016 extreme precipitation event in Louisiana. The basic premise of this report is as follows:

“The media, the public, and decision makers increasingly ask for results from event attribution studies during or directly following an extreme event. To meet this need, some groups are developing rapid and/or operational event attribution systems to provide attribution assessments on faster timescales than the typical research mode timescale, which can often take years.”

If you have established a free NAP account, you can download a pdf copy of this report for free at the following link:

The second NAP report, “Frontiers of Decadal Climate Variability,” addresses a longer-term climate issue. This report documents the results of a September 2015 workshop convened by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to examine variability in Earth’s climate on decadal timescales, which they define as 10 to 30 years.

This report puts the importance of understanding decadal climate variability in the following context:

“Many factors contribute to variability in Earth’s climate on a range of timescales, from seasons to decades. Natural climate variability arises from two different sources: (1) internal variability from interactions among components of the climate system, for example, between the ocean and the atmosphere, and (2) natural external forcing (functions), such as variations in the amount of radiation from the Sun. External forcing (functions) on the climate system also arise from some human activities, such as the emission of greenhouse gases (GHGs) and aerosols. The climate that we experience is a combination of all of these factors.

Understanding climate variability on the decadal timescale is important to decision-making. Planners and policy makers want information about decadal variability in order to make decisions in a range of sectors, including for infrastructure, water resources, agriculture, and energy.”

While decadal climate variability is quite different than specific extreme weather events, the decadal variability establishes the underlying climate patterns on which extreme weather events may occur.

You can download a pdf copy of this report for free at the following link:

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/23552/frontiers-in-decadal-climate-variability-proceedings-of-a-workshop

I think it’s fair to say that, in the future, we will be seeing an increasing number of “quick response” attributions of extreme weather events to climate change. Each day in the financial section of the newspaper (Yes, I still get a printed copy of the daily newspaper!), there is an attribution from some source about why the stock market did what it did the previous day. Some days these financial attributions seem to make sense, but other days they’re very much like reading a fortune cookie or horoscope, offering little more than generic platitudes.

Hopefully there will be real science behind attributions of extreme weather events to climate change and the attributors will heed WWA’s caution:

“…it is important for every extreme event attribution study to clearly define the event and state the framing of the attribution question.”