Peter Lobner, updated 24 Jan 2019, 12 Nov 2019 and 17 October 2023

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) durable New Horizon spacecraft made its close flyby of Pluto on 14 July 2015, passing 7,800 mi (12,500 km) above the surface of that dwarf planet and returning a remarkable trove of photos and data. Since then, the spacecraft has been continuing its journey out of our solar system and now is flying through the Kuiper Belt, which is a very large, diffuse region beyond the orbit of Neptune containing millions of small bodies in distant orbits around the Sun. These Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) are believed to be “leftovers” (i.e., they never coalesced into planets) from the formation of the early solar system. You can read more about the Kuiper Belt on the NASA website here:

https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/solar-system/kuiper-belt/overview/

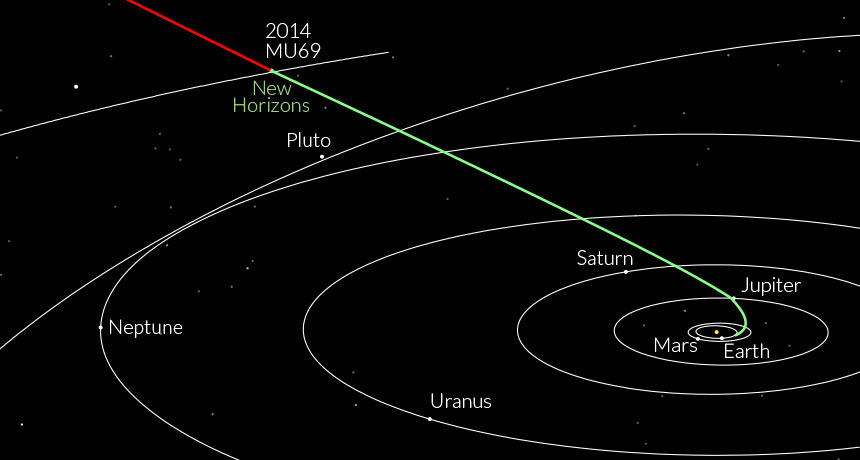

On 28 August 2015, NASA announced that it had selected the next destination for New Horizons after the Pluto flyby: a small KBO designated 2014 MU69, originally named Ultima Thule, about 1 billion miles (1.6 billion km) beyond Pluto. The spacecraft’s trajectory from Earth to Ultima Thule is shown in the following NASA diagram.

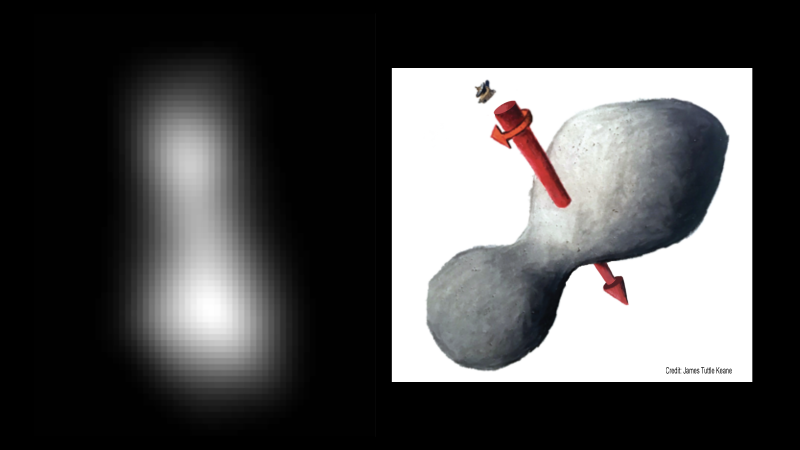

On 1 January 2019, the New Horizons spacecraft made a close flyby of 2014 MU69, at a range of 2,200 miles (3,500 km) and a relative speed of 14 kilometers per second (31,317 mph). At a distance of 4.1 billion miles (6.6 billion km) from the Earth, radio signals took 6 hours and 6 minutes traveling at the speed of light to traverse the distance between the spacecraft and Earth during the encounter. On 1 January 2019, NASA released the following blurry image, which was taken at long range.

NASA reported: “At left is a composite of two images taken by New Horizons’ high-resolution Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI), which provides the best indication of Ultima Thule’s size and shape so far. Preliminary measurements of this Kuiper Belt object suggest it is approximately 20 miles long by 10 miles wide (32 kilometers by 16 kilometers). An artist’s impression at right illustrates one possible appearance of Ultima Thule, based on the actual image at left. The direction of Ultima’s spin axis is indicated by the arrows. “

In the weeks following the flyby, New Horizons will be downloading all of the higher-resolution photos and data acquired during its close encounter with 2014 MU69 and we’ll be getting a much more detailed understanding of this KBO.

It appears that NASA has the opportunity to target one or more additional KBOs for future New Horizons flybys in the 2020s. The spacecraft’s electric power source, a plutonium (Pu-238)-fueled radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG), is capable of providing power well into the 2030s, albeit at gradually reducing power levels. In addition, the spacecraft has significant hydrazine fuel remaining for course correction and attitude control en route to a future KBO flyby.

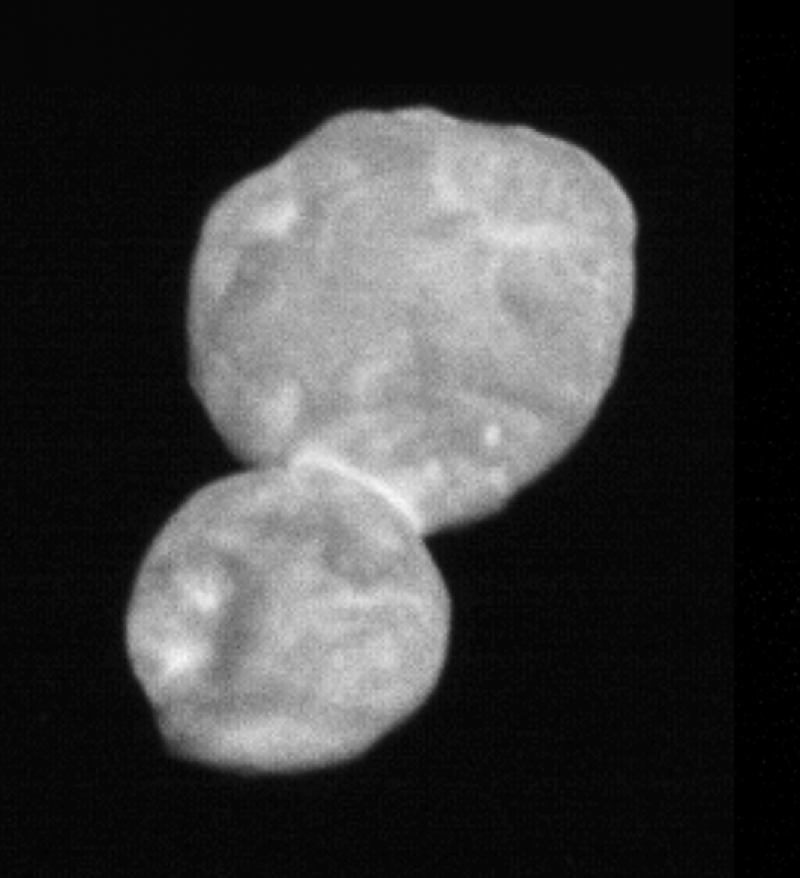

On 2 January 2019, NASA released the following photo taken on the inbound leg of the flyby, still 18,000 miles (28,000 km) from 2014 MU69.

You’ll find more information on NASA’s New Horizons mission here:

https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/newhorizons/main/index.html

24 January 2019 update: Latest photo shows 2014 MU69 surface to be unusually smooth

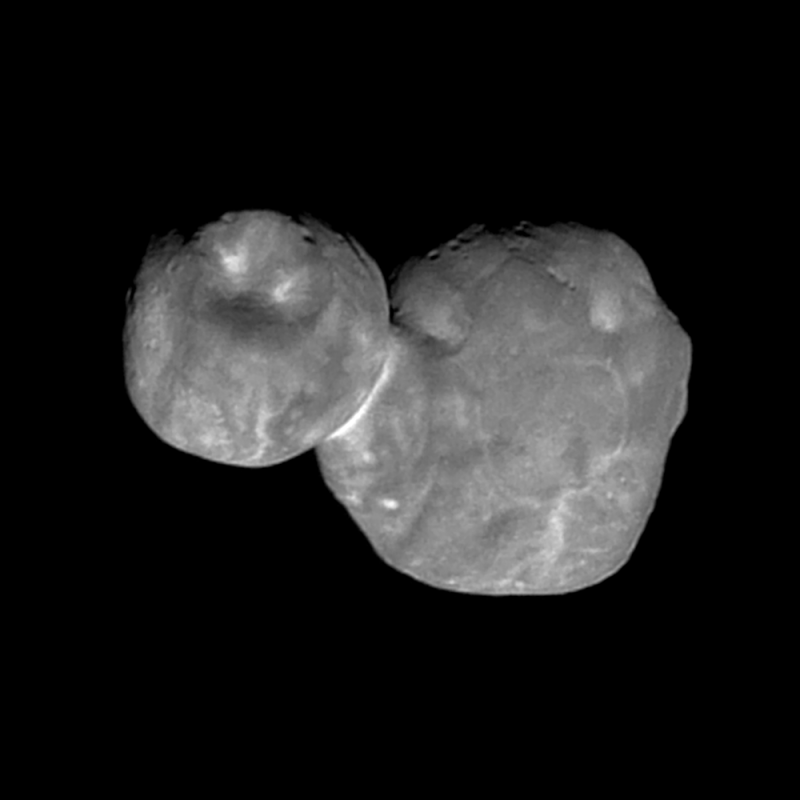

Today, NASA released the following photo of 2014 MU69, taken at a distance of 4,200 miles (6,700 kilometers) on 1 January 2019, just seven minutes before closest approach. Principal Investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute, reported, “Over the next month there will be better color and better resolution images that we hope will help unravel the many mysteries of Ultima Thule.”

12 November 2019 update: 2014 MU69 renamed

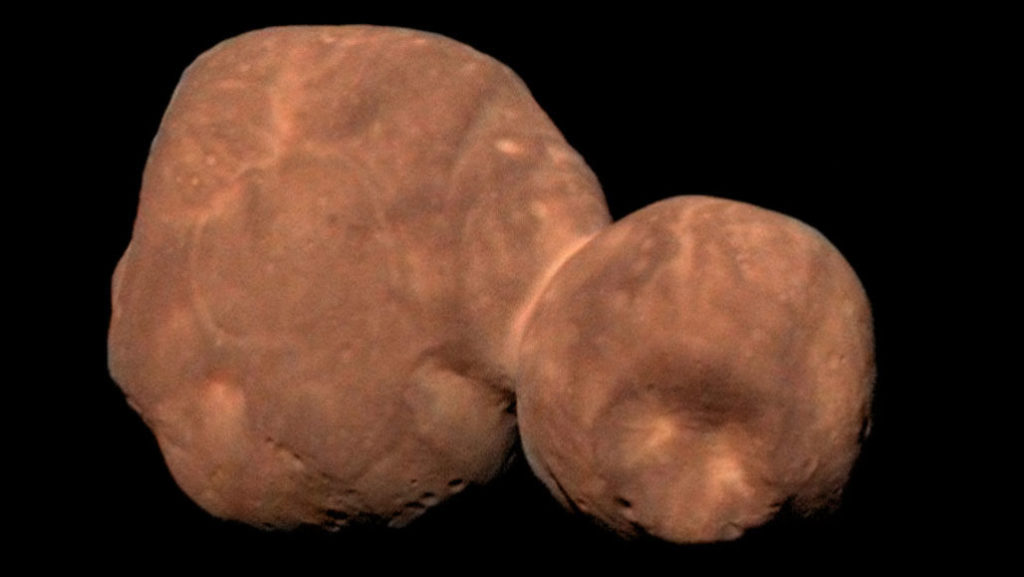

NASA announced that 2014 MU69 was formally renamed “Arrokoth”, which NASA says “means ‘sky’ in the language of the Powhatan people, a Native American tribe indigenous to Maryland. The state is home to New Horizons mission control at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel.” Here’s a colorized view of Arrokoth.

17 October 2023 update: Analysis of Arrokoth’s structure

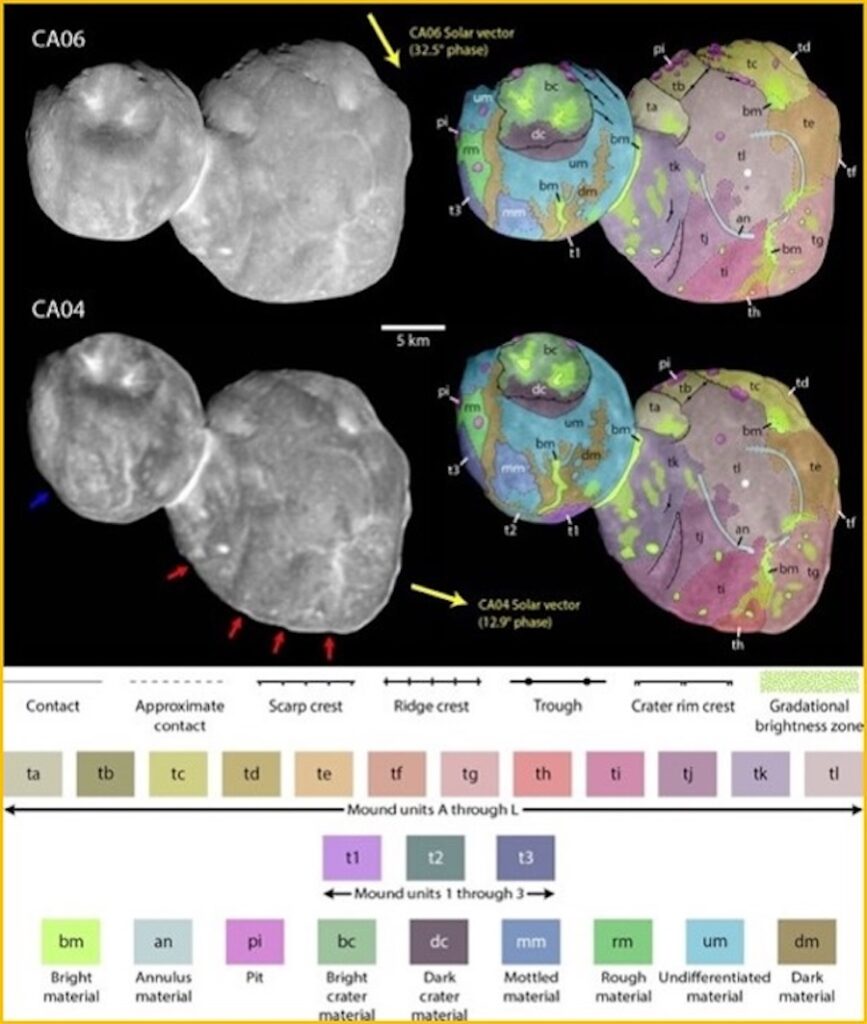

In September 2023, a research team from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado reported the results of their detailed analysis of Arrokoth, focusing on 12 mounds identified on the larger lobe, named Wenu, and tentatively, three on the smaller lobe, named Weeyo.

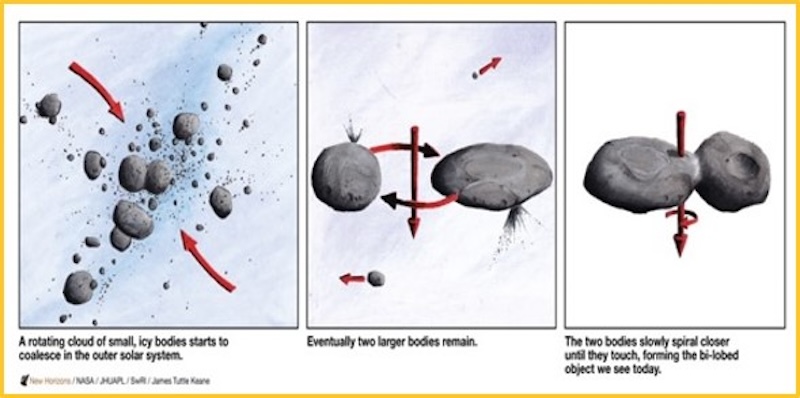

As reported by EarthSky, “The data from New Horizons suggest that the mounds have a common origin. In this case, that common origin would date back to when Arrokoth first formed billions of years ago. As with planets and moons, the Kuiper Belt object formed when various chunks and bits of material collided together, creating the larger planetesimal now known as Arrokoth.” This formation process is shown in the following diagram.

Data from New Horizons suggests that Arrokoth formed from material that collided together at slow speeds. Source: New Horizons/ NASA/ JHUAPL/ SwRI/ James Tuttle Keane.

The locations and structure of the mounds on Arrokoth are shown in the following graphic.

The mound structures dominate Arrokoth’s larger lobe (named Wenu). In addition, there are a few tentative mounds identified on the smaller lobe (named Weeyo). Source: SwRI via EarthSky

For more information

- Paul Scott Anderson, “Are the mystery mounds on Arrokoth ancient building blocks?” EarthSky, 16 October 2023: https://earthsky.org/space/mounds-on-arrokoth-kuiper-belt-object-planetesimals-new-horizons/

- S.A. Stern, et al., “The Properties and Origin of Kuiper Belt Object Arrokoth’s Large Mounds,” The Planetary Science Journal, 4, 176, 26 September 2023: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/PSJ/acf317