Peter Lobner

Updated 9 January 2020

The LCS program consists of two different, but operationally comparable ship designs:

- LCS-1 Freedom-class monohull built by Marinette Marine

- LCS-2 Independence-class trimaran built by Austal USA.

These relatively small surface combatants have full load displacements in the 3,400 – 3,900 ton range, making them smaller than most destroyer and frigate-class ships in the world’s navies.

LCS-2 in foreground & LCS-1 in background. Source: U.S. Navy

LCS-2 in foreground & LCS-1 in background. Source: U.S. Navy LCS-1 on left & LCS-2 on right. Source: U.S. Navy

LCS-1 on left & LCS-2 on right. Source: U.S. Navy

Originally LCS was conceived as a fleet of 52 small, fast, multi-mission ships designed to fight in littoral (shallow, coastal) waters, with roll-on / roll-off mission packages intended to give these ships unprecedented operational flexibility. In concept, it was expected that mission module changes could be conducted in any port in a matter of hours. In a 2010 Department of Defense (DoD) Selected Acquisition Report, the primary missions for the LCS were described as:

“…littoral surface warfare operations emphasizing prosecution of small boats, mine warfare, and littoral anti-submarine warfare. Its high speed and ability to operate at economical loiter speeds will enable fast and calculated response to small boat threats, mine laying and quiet diesel submarines. LCS employment of networked sensors for Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) in support of Special Operations Forces (SOF) will directly enhance littoral mobility. Its shallow draft will allow easier excursions into shallower areas for both mine countermeasures and small boat prosecution. Using LCS against these asymmetrical threats will enable Joint Commanders to concentrate multi-mission combatants on primary missions such as precision strike, battle group escort and theater air defense.”

Both competing firms met a Congressionally-mandated cost target of $460 million per unit, and, in December 2010, Congress gave the Navy authority to split the procurement rather than declare a single winner. Another unique aspect of the LCS program was that the Defense Acquisition Board split the procurement further into the following two separate and distinct programs with separate reporting requirements:

- The two “Seaframe” programs (for the two basic ship designs, LCS-1 and LCS-2)

- The Mission Module programs (for the different mission modules needed to enable an LCS seaframe to perform specific missions)

When the end product is intended to be an integrated combatant vessel, you don’t need to be a systems analyst to know that trouble is brewing in the interfaces between the seaframes and the mission modules somewhere along the critical path to LCS deployment.

There are three LCS mission modules:

- Surface warfare (SUW)

- Anti-submarine (ASW)

- Mine countermeasures (MCM)

These mission modules are described briefly below:

Surface warfare (SUW)

Each LCS is lightly armed since its design basis surface threat is an individual small, armed boat or a swarm of such boats. The basic anti-surface armament on an LCS seaframe includes a single 57 mm main gun in a bow turret and everal small (.50 cal) machine guns. The SUW module adds twin 30mm Bushmaster cannons, an aviation unit, a maritime security module (small boats), and relatively short-range surface-to-surface missiles.

Each LCS has a hanger bay for its embarked aviation unit, which is comprised of one manned MH-60R Sea Hawk helicopter and one MQ-8B Fire Scout unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV, a small helicopter). As part of the SUW module, these aviation assets are intended to be used to identify, track, and help prosecute surface targets.

That original short-range missile collaboration with the Army failed when the Army withdrew from the program. As of December 2016, the Navy is continuing to conduct operational tests of a different Army short-range missile, the Longbow Hellfire, to fill the gap in the SUW module and improve the LCS’s capability to defend against fast inshore attack craft.

In addition to the elements of the SUW module described above, each LCS has a RIM-116 Rolling Airframe Missile (RAM) system or a SeaRAM system intended primarily for anti-air point defense (range 5 – 6 miles) against cruise missiles. A modified version of the RAM has limited capabilities for use against helicopters and nearby small surface targets.

In 2015, the Navy redefined the first increment of the LCS SUW capability as comprising the Navy’s Visit, Board, Search and Seizure (VBSS) teams. This limited “surface warfare” function is comparable to the mission of a Coast Guard cutter.

While the LCS was not originally designed to have a long-range (over the horizon) strike capability, the Navy is seeking to remedy this oversight and is operationally testing two existing missile systems to determine their suitability for installation on the LCS fleet. These missiles are the Boeing Harpoon and the Norwegian Konigsberg Naval Strike Missile (NSM). Both can be employed against sea and land targets.

Anti-submarine (ASW)

The LCS does not yet have an operational anti-submarine warfare (ASW) capability because of ongoing delays in developing this mission module.

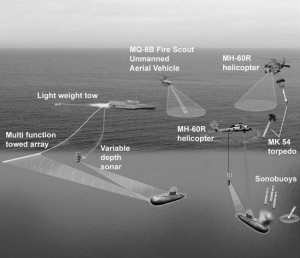

The sonar suite is comprised of a continuously active variable depth sonar, a multi-function towed array sonar, and a torpedo defense sonar. For the ASW mission, the MH-60R Sea Hawk helicopter will be equipped with sonobuoys, dipping sonar and torpedoes for prosecuting submarines. The MQ-8B Fire Scout UAV also can support the ASW mission.

Use of these ASW mission elements is shown in the following diagram (click on the graphic to enlarge):

In 2015, the Navy asked for significant weight reduction in the 105 ton ASW module.

Originally, initial operational capability (IOC) was expected to be 2016. It appears that the ASW mission package is on track for an IOC in late 2018, after completing development testing and initial operational test & evaluation.

Mine Countermeasures (MCM)

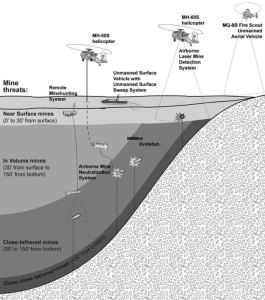

The LCS does not yet have an operational mine countermeasures capability. The original complex deployment plan included three different unmanned vehicles that were to be deployed in increments.

- Lockheed Martin Remote Multi-mission Vehicle (RMMV) would tow a sonar system for conducting “volume searches” for mines

- Textron Common Unmanned Surface Vehicle (CUSV) would tow minesweeping hardware.

- General Dynamics Knifefish unmanned underwater vehicle would hunt for buried mines

For the MCM mission, the MH-60R Sea Hawk helicopter will be equipped with an airborne laser mine detection system and will be capable of operating an airborne mine neutralization system. The MQ-8B Fire Scout UAV also supports the MCM mission.

Use of these MCM mission elements is shown in the following diagram (click on the graphic to enlarge):

Original IOC was expected to be 2014. The unreliable RMMV was cancelled in 2015, leaving the Navy still trying in late 2016 to define how an LCS will perform “volume searches.” CUSV and Knifefish development are in progress.

It appears the Navy is not planning to conduct initial operational test & evaluation of a complete MCM module before late 2019 or 2020.

By January 2012, the Navy acknowledged that mission module change-out could take days or weeks instead of hours. Therefore, each LCS will be assigned a single mission, making module changes a rare occurrence. So much for operational flexibility.

LCS has become the poster child for a major Navy ship acquisition program that has gone terribly wrong.

- The mission statement for the LCS is still evolving, in spite of the fact that 26 already have been ordered.

- There has been significant per-unit cost growth, which is actually difficult to calculate because of the separate programmatic costs of the seaframe and the mission modules.

- FY 2009 budget documents showed that the cost of the two lead ships had risen to $637 million for LCS-1 Freedom and $704 million for LCS-2

- In 2009, Lockheed Martin’s LCS-5 seaframe had a contractual price of $437 million and Austal’s LCS-6’s seaframe contractual price was $432 million, each for a block of 10 ships.

- In March 2016, General Accounting Office (GAO) reported the total procurement cost of the first 32 LCSs, which worked out to an average unit cost of $655 million just for the basic seaframes.

- GAO also reported the total cost for production of 64 LCS mission modules, which worked out to an average unit cost of $108 million per module.

- Based on these GAO estimates, a mission-configured LCS (with one mission module) has a total unit cost of about $763 million.

- In 2016, the GAO found that, “the ship would be less capable of operating independently in higher threat environments than expected and would play a more limited role in major combat operations.”

- The flexible mission module concept has failed. Each ship will be configured for only one mission.

- Individual mission modules are still under development, leaving deployed LCSs without key operational capabilities.

- The ships are unreliable. In 2016, the GAO noted the inability of an LCS to operate for 30 consecutive days underway without a critical failure of one or more essential subsystems.

- Both LCS designs are overweight and are not meeting original performance goals.

- There was no cathodic corrosion protection system on LCS-1 and LCS-2. This design oversight led to serious early corrosion damage and high cost to repair the ships.

- Crew training time is long.

- The original maintenance plans were unrealistic.

- The original crew complement was inadequate to support the complex ship systems and an installed mission module.

To address some of these issues, the LCS crew complement has been increased, an unusual crew rotation process has been implemented, and the first four LCSs have been withdrawn from operational service for use instead as training ships.

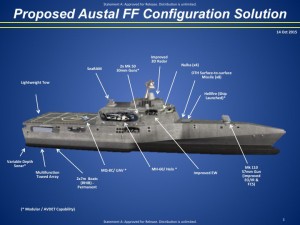

To address some of the LCS warfighting limitations, the Navy, in February 2014, directed the LCS vendors to submit proposals for a more capable vessel (originally called “small surface combatant”, now called “frigate” or FF) that could operate in all regions during conflict conditions. Key features of this new frigate include:

- Built-in (not modular) anti-submarine and surface warfare mission systems on each FF

- Over-the-horizon strike capability

- Same purely defensive (point defense) anti-air capability as the LCS. Larger destroyers or cruisers will provide fleet air defense.

- Lengthened hull

- Lower top speed and less range

As you would expect, the new frigate proposals look a lot like the existing LCS designs. In 2016, the GAO noted that the Navy prioritized cost and schedule considerations over the fact that a “minor modified LCS” (i.e., the new frigate) was the least capable option considered.” The competing designs for the new frigate are shown below (click on the graphic to enlarge):

Source: U.S. Navy

Source: U.S. Navy Source: U.S. Navy

Source: U.S. Navy

GAO reported the following estimates for the cost of the new multi-mission frigate and its mission equipment:

- Lead ship: $732 – 754 million

- Average ship: $613 – 631 million

- Average annual per-ship operating cost over a 25 year lifetime: $59 – 62 million

Note that the frigate lead ship cost estimate is less than the GAO’s estimated actual cost of an average LCS plus one mission module. Based on the vendor’s actual LCS cost control history, I’ll bet that the GAO’s frigate cost estimates are just the starting point for the cost growth curve.

To make room for the new frigate in the budget and in the current 308-ship fleet headcount limit, the Navy reduced the LCS buy to 32 vessels, and planed to order 20 new frigates from a single vendor. In December 2015, the Navy reduced the total quantity of LCS and frigates from 52 to 40. By mid-2016, Navy plans included only 26 LCS and 12 frigates.

2016 Top Ten Most Powerful Frigates in the World

To see what international counterparts the LCS and FF are up against, check out the January 2016 article, “Top Ten Most Powerful Frigates in the World,” which includes frigates typically in the 4,000 to 6,900 ton range (larger than LCS). You’ll find this at the following link:

https://defencyclopedia.com/2016/01/02/top-10-most-powerful-frigates-in-the-world/

There are no U.S. ships in this top 10.

So what do you think?

- Are the single-mission LCSs really worth the Navy’s great investment in the LCS program?

- Will the two-mission FFs give the Navy a world-class frigate that can operate independently in contested waters?

- Would you want to serve aboard an LCS or FF when the fighting breaks out, or would you choose one of the more capable multi-mission international frigates?

Update: 9 January 2020

A 5 April 2019 article in The National Interest reported:

“The Pentagon Operational Test & Evaluation office’s review of the LCS fleet published back in January 2018 revealed alarming problems with both Freedom and Independence variants of the line, including: concerning issues with combat system elements like radar, limited anti-ship missile self-defense capabilities, and a distinct lack of redundancies for vital systems necessary to reduce the chance that “a single hit will result in loss of propulsion, combat capability, and the ability to control damage and restore system operation…..Neither LCS variant is survivable in high-intensity combat,” according to the report.”

The article’s link to the referenced 2018 Pentagon DOT&E report now results on a “404 – Page not found!” message on the DoD website. I’ve been unable to find that report elsewhere on the Internet. I wonder why? See for yourself here: https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/no-battleship-littoral-combat-ship-might-be-navys-worst-warship-50882

I’d chalk the LCS program up as a huge failure, delivering unreliable, poorly-armed ships that do not yet have a meaningful, operational role in the U.S. Navy and have not been integrated as an element of a battle group. I think others agree. The defense bill signed by President Trump in December 2019 limits LCS fleet size and states that none of the authorized funds can be used to exceed “the total procurement quantity of 35 Littoral Combat Ships.” Do I hear an Amen?

For more information:

A lot of other resources are available on the Internet describing the LCS program, early LCS operations, the LCS-derived frigate program, and other international frigates programs. For more information, I recommend the following resources dating from 2016 to 2019:

- “Navy Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) Program: Background and Issues for Congress,” RL33741 (updated), Congressional Research Service, updated 17 December 2019: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33741/257

- “Littoral Combat Ship and Frigate: Delaying Planned Frigate Acquisition Would Enable Better-Informed Decisions, “ GAO-17-323, General Accounting Office, 18 April 2017: https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-17-323

- “Need to Address Fundamental Weaknesses in LCS and Frigate Acquisition Strategies,” GAO-16-356, General Accounting Office, June 2016: https://www.gao.gov/assets/680/677764.pdf

- “Storm-Tossed: The Controversial Littoral Combat Ship,” Breaking Defense, November 2016. The website Breaking Defense (http://breakingdefense.com) is an online magazine that offers defense industry news, analysis, debate, and videos. Their free eBook collects their coverage of the Navy’s LCS program. You can get a copy at the following link: http://info.breakingdefense.com/littoral-combat-ship-ebook