Peter Lobner

In an effort to improve the generating and economic performance of wind turbines, manufacturers have been designing and building increasingly larger machines. Practical limits on transporting these very long and heavy components between the factories and the installation sites may limit the scale of the wind turbines selected for some applications and may require novel solutions that affect component design, factory siting and choice of transportation mode. In this post, we’ll take a look at these issues.

1. The latest generation of wind turbines

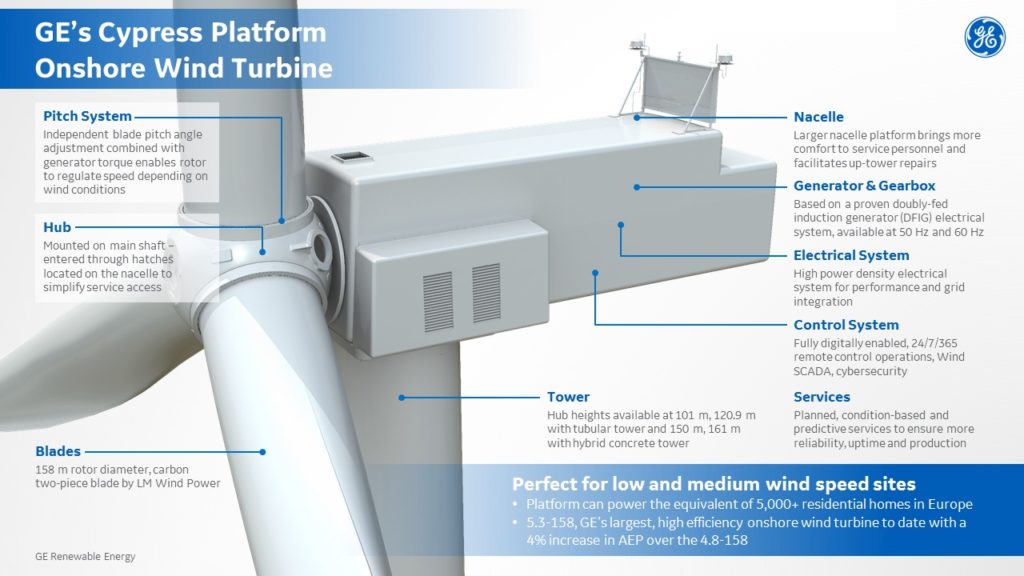

1.1 GE Cypress platform

On 13 March 2019, General Electric (GE) Renewable Energy announced that its largest onshore wind turbine prototype, named Cypress, started commercial operation in the Netherlands. Unlike other large wind turbines, the prototype Cypress composite turbine blades come in two pieces and are assembled on site. Cypress was announced in September 2017 and construction of the prototype began in 2018.

The Cypress 5.3-158 prototype has a nominal generating capacity of 5.3 MW. A smaller Cypress 4.8-158 (with a 4.8 MW rating) is currently under production at GE’s Salzbergen, Germany factory, and it is expected to be commissioned by the end of the 2019. Both have a rotor diameter of 158 meters (518.3 ft).

GE reports that the Cypress platform is “powered by a revolutionary two-piece blade design that makes it possible to use larger rotors and site the turbines in a wider variety of locations. The Annual Electricity Production (AEP) improvements from the longer rotors help to drive down Levelized Cost of Electricity (LCOE), and the proprietary blade design allows these larger turbines to be installed in locations that were previously inaccessible.” Site accessibility can be limited by the practicality of ground transportation of single-piece blades that can be nearly 91.4 meters (300 feet) long.

1.2 GE LM 88.4 P, the longest one-piece rotor blade in the world

LM Wind Power, a GE Renewable Energy business, has delivered the longest one-piece wind turbine blades built to date, the LM 88.4 P, which measure 88.4 meters (290 ft) long. Three of these giant blades are installed onshore in Denmark on an Adwen’s AD 8-180 wind turbine, which has an 8 MW nominal generating capacity and a 180 meter (590.5 ft) rotor diameter. You can get a sense of the size of an LM 88.4 P in the following photo showing a rotor blade leaving the factory.

leaving the factory. Source: LM Wind Power

1.3 GE Haliade-X platform

GE is developing an even larger wind turbine platform, the Haliade X, which will become the world’s largest wind turbine when it is completed. This 12 MW platform, which is being developed primarily for offshore wind farms, features 107 meter (351 ft) long one-piece blades and a 220 meter (722 ft) rotor diameter. The first prototype unit will be installed onshore near Rotterdam, Netherlands, where it will stand 259 meters (850 ft) tall, from the base of the tower to the top of the blade sweep.

Construction of the prototype Haliade-X wind turbine began in 2019. The first blade is shown in the photo below. After securing a “type certificate” for the Haliade-X platform, GE plans to start selling this wind turbine commercially as early as 2021. The near-term market focus appears to be new wind turbines sited in the North Sea.

1.4 Siemens Gamesa SG 10.0-193 DD platform

In January 2019, Siemens Gamesa launched its next generation (Generation V) of very large offshore wind turbines, the SG 10.0-193 DD, which has a nominal generator rating of 10 MW, blade length of 94 meters (308 ft) and a rotor diameter of 193 meters (633 ft). The nacelle housing the wind turbine hub and generator weighs up to 400 tons.

You’ll find the Siemens product brochure for this Generation V wind turbine here: https://www.siemensgamesa.com/en-int/-/media/siemensgamesa/downloads/en/products-and-services/offshore/brochures/siemens-gamesa-offshore-wind-turbine-sg-10-0-193-dd-en-double.pdf

1.5 Vestas EnVestusTM platform

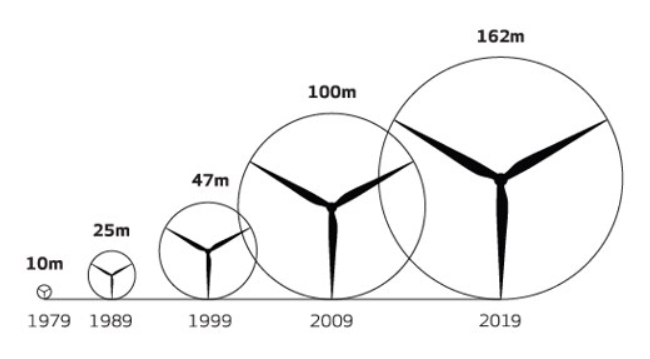

The EnVestusTM platform, which was introduced in 2019, is Vestas’ next generation in its evolution of wind turbines. The V162-5.6 MW has a rotor diameter of 162 meters (531 ft), which is the largest rotor size offered in the current EnVestusTM product portfolio. Various tower sizes are offered, with hub heights up to 166 meters (545 ft). With this tallest tower, the blade sweep of a V162-5.6 MW wind turbine reaches a height of 247 meters (810 ft).

The trend in Vestas wind turbine maximum rotor size is evident in the following diagram. In comparison, the largest GE wind turbine, the Haliade-X will have a rotor diameter of 220 meter (722 ft), and the largest Siemens Generation V wind turbine will have a rotor diameter of 193 meters (633 ft).

You can read and download the EnVestusTMproduct line brochure here: https://nozebra.ipapercms.dk/Vestas/Communication/Productbrochure/enventus/enventus-product-brochure/?page=1

2. Transporting very large wind turbine components

The manufacturer’s efforts to improve wind turbine generating and economic performance has resulted in increasingly larger machine components, which are challenging the limits of today’s transportation infrastructure as the components are moved from the manufacturer’s factories to the installation sites. Here, we’ll look at the various ways these large components are transported.

2.1 Transportation of wind turbine components by land

Popular Mechanics reported that, “Moving long turbine blades is such a logistical nightmare that the companies involved sometimes resort to building new roads for the sole purpose of moving blades.” Transporting wind turbine tower and nacelle components can be equally challenging. You’ll find an interesting assessment by CGS Labs of the challenges of wind farm ground transportation planning at the following link: https://www.cgs-labs.com/Software/Autopath/Articles/Windturbinetransport.aspx

As noted previously, the GE one-piece LM 88.4 P, which is 88.4 meters (290 ft) long, is the longest wind turbine rotor blade currently in service. You can watch a short video of a single LM 88.4 P blade being transported 218 km (135 miles) to the construction site at the following link. Total transport weight was 60 tons (120,000 lb, 54,431 kg). https://www.lmwindpower.com/en/products-and-services/blade-types/longest-blade-in-the-world

Source: Screenshot from LM Wind Power video

Specialized trucks are employed to negotiate existing roads. Examples of difficult transportation situations are shown in the following photos.

Vestas V117 57.5 meter (189 ft) wind turbine blade.

Source: CNN.com, 5 October 2017

Watch a short 2017 video of this maneuver here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rxvuMv2MED0

Watch a short 2015 video of this amazing truck convoy here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1cnHui4pFBU

2.2. Transportation of wind turbine components by sea

The single-piece blades for the GE Haliade X wind turbine are so long that they couldn’t be transported by land from GE’s existing factories. Therefore, a new LM Wind Power blade factory for the offshore wind market was built in Cherbourg, France, on the banks of the English Channel in Normandy. This factory can load blades directly onto ships for delivery to offshore wind turbine sites.

Source: LM Wind Power

In December 2016, Siemens Gamesa reported, “When our new factories in Hull, England and Cuxhaven, Germany become fully operational, and both Ro-Ro (“roll-on, roll-off”) vessels are in service as interconnection of our manufacturing and installation network, we expect savings of 15-20 percent in logistics costs compared to current transport procedures. This is another important contributor reducing the cost of electricity from offshore wind.”

The Hull, UK rotor blade factory, located at the Alexandra Docks on the harbor, was completed in 2016. The Esbjerg, Denmark factory also is located on the harbor with direct access to shipping.

In 2018, Siemens Gamesa opened its modern factory in Cuxhaven, Germany for manufacturing offshore wind turbine nacelles. These three Siemens wind turbine factories have direct Ro-Ro access to shipping.In November 2016, Siemens commissioned its first specialized Ro-Ro transport vessel, the Rotra Vente. This ship is designed to transport multiple heavy nacelles, or up to nine tower sections, or three to four sets of rotor blades, depending on what else is being transported. A second specialized Ro-Ro transport vessel, the Rotra Mare, was commissioned in the spring of 2017 to transport tower sections and up to 12 rotor blades. These specialized transport vessels link the Siemens factories and transport the finished wind turbine components to the respective installation harbor.

2.3. Transportation of wind turbine components by airship

For more than two decades, there has been significant interest in the use of modern lighter-than-air craft and hybrid airships in a variety of heavy-lift roles. One such role is the transportation of large wind turbine components. Airships offer the potential to transport the components quickly between factory and installation site without the constraints of current ground and sea transportation networks.

Three examples of airship concepts for transporting wind turbine components are described below.

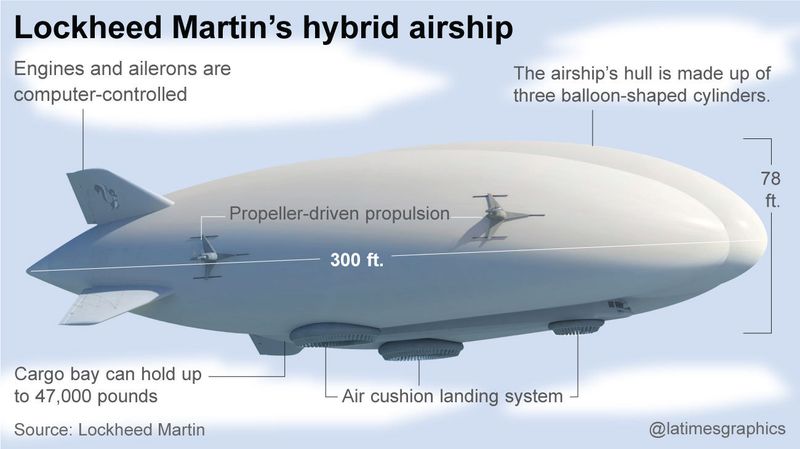

Hybrid airships

In 2017, Lockheed-Martin proposed its LMH-1 hybrid airship to deliver large wind turbine components weighing up to 23.5 tons (47,000 lb; 21,000 kg). The LMH-1 will be capable of flying 1,400 nautical miles (2,593 km) at a speed of about 70 knots (80 mph, 129 kph). Lockheed-Martin is expected to fly the commercial prototype of its LMH-1 hybrid airship in 2019. You can read Lockheed-Martin’s proposal for airship transport of wind turbine components here: https://www.lockheedmartin.com/content/dam/lockheed-martin/eo/documents/webt/transporting-wind-turbine-blades.pdf

This type of airship conducts short takeoff and landing (STOL) operations when transporting heavy loads, but can operate from relatively unprepared sites. When off-loading heavy cargo, this airship must take on ballast at the landing site.

After LMH-1, Lockheed Martin has plans to build a medium-size (90 ton cargo) hybrid airship that would be more competitive with trucking and rail transport.

Variable buoyancy airships

In January 2013, Worldwide Aeros Corp. (Aeros), located in Montebello, CA, conducted the first “float test” of their Dragon Dream variable buoyancy airship. More recently, Aeros has reported that they are working on the first commercial prototype of a larger variable buoyancy airship to be known as the ML866 / Aeroscraft Gen 2, which will be 169 meters (555 ft) long. This airship is being designed with great range (3,100 nautical miles; 5,741 km) and a cruise speed of 100 – 120 knots. The ML866 will have a cargo capacity of 66 tons (132,000 lb; 59,874 kg). The first ML866 prototype is not expected to fly before the early 2020s.

This type of airship is designed to conduct vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) operations with a full cargo load, and can hover above a site and take on or deliver cargo without landing and without transferring ballast to/from the ground site.

Semi-rigid airships

The KNARR initiative is a project created by two Danish design architects, Rune Kirt and Mads Thomsen to design a freight solution using modern airships to reduce the cost and energy consumption of today’s wind turbine freight business and make the logistics for wind turbine freight simpler and more efficient. Their main point is that transportation and installation costs can be up to 60% of the total cost of a new wind turbine, and these activities have a large carbon footprint. Their solution is a modern airship that is designed specifically for transporting very large and heavy wind turbine components directly from the manufacturer’s factory to the installation site. For their work, they were awarded both the Danish Design Center’s Special Prize and the International Core77 Design “Speculative Concept.”. You can read more about the firm, KIRT x THOMSEN aps, and the KNARR initiative here: https://www.kirt-thomsen.com/case10_airship-knarr

and here: https://projectknarr.wordpress.com/what-is-knarr/

The KNARR semi-rigid airship would be 360 meters (1,181 ft) long and would carry the wind turbine components in a large internal cargo bay. This type of airship is designed to conduct VTOL operations with a full cargo load. When off-loading heavy cargo, this airship must take on ballast at the landing site.

The KNARR airship is a concept only. No prototype is being built at this time. You can view a short video defining the wind turbine transport application of KNARR airship here: https://vimeo.com/21023051

Source: https://www.kirt-thomsen.com/

Source: https://www.kirt-thomsen.com/

3. Conclusions

The scale of the latest generation of wind turbines, particularly the GE LM 88.4 P, which measure 88.4 meters (290 ft) long, is approaching the limits of existing ground transportation infrastructure to handle delivery of such blades from the factory to the installation site. GE’s introduction of two-piece blades on their new Cypress platform will significantly improve the logistics for delivering these large blades to installation sites.

Siemens’ practice of siting its wind turbine component factories with ready access to Ro-Ro shipping at an adjacent port facility greatly reduces the complexity of delivering large components to a port near an installation site. GE has adopted the same approach with their latest factory for manufacturing the Haliad-X rotor blades in Cherbourg, France, on the English Channel.

Airships could revolutionize the transportation of large, heavy items such as wind turbine components. However, the earliest likely candidate, the Lockheed Martin LMH-1 will not be available until the early 2020s and will be limited to a maximum load of 23.5 tons (47,000 lb; 21,000 kg). It seems unlikely that larger heavy-lift airships will be introduced before about 2025.

So, in the meantime, we’ll see the largest wind turbines being installed in offshore sites. For onshore sites, we’ll see more creative ground transportation schemes, and, probably, a broader introduction of multi-part rotor blades.

4. Recommended additional reading on wind turbines:

- David Roberts, “These huge new wind turbines are a marvel. They’re also the future,” 20 May 2019 https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/2018/3/8/17084158/wind-turbine-power-energy-blades

- Kevin Smith & Dayton Griffin, “Supersized Wind Turbine Blade Study – R&D Pathways for Supersized Wind Turbine Blades,” Report 10080081-HOU-R-01, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 7 March 2019 https://cloudfront.escholarship.org/dist/prd/content/qt0vr6b23m/qt0vr6b23m.pdf?t=po2ds6

- Michelle Froese, “The rise of wind power: what to expect in 2019,” Windpower Engineering Development, 11 January 2019 https://www.windpowerengineering.com/business-news-projects/the-rise-of-wind-power-what-to-expect-in-2019/