Peter Lobner

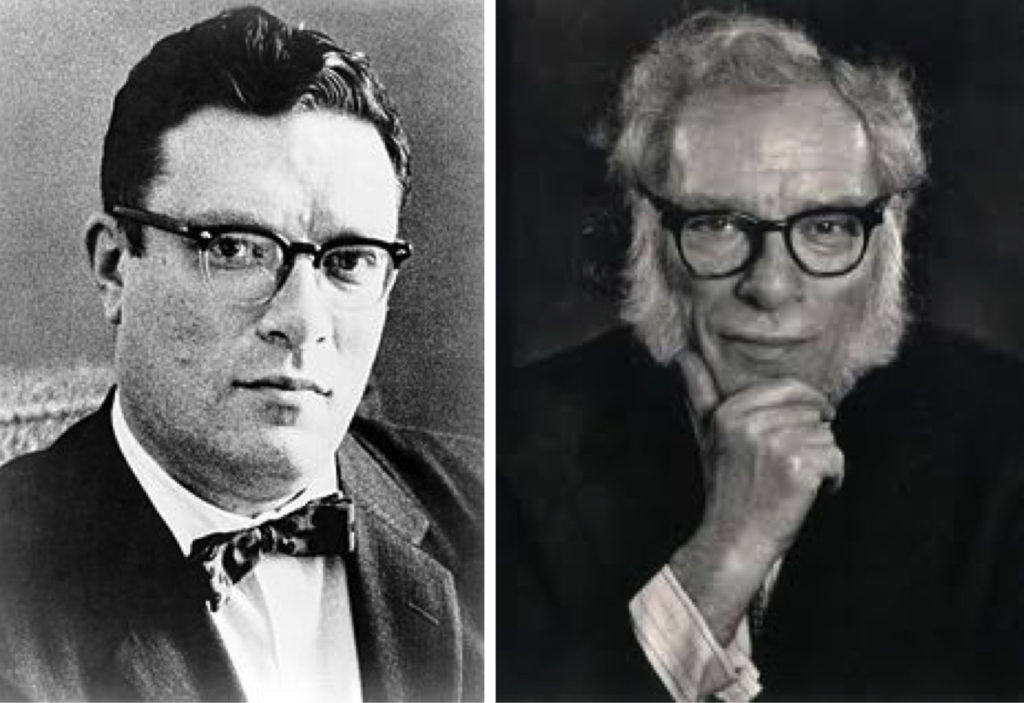

The birthdate of Isaac Asimov, a famous author best known for his science fiction novels and short stories, is sometime between 4 October 1919 and 2 January 1920. He was born in Petrovichi in Smolensk Oblast, RSFSR (now Russia), west of Moscow, near the border with Belarus, and he died in New York City on 6 April 1992. He traditionally celebrated his birthday on 2 January, giving enough reason to mark the centennial of his birth on 2 January 2020.

You’ll find short biographies of Isaac Asimov at the following links:

https://www.biography.com/writer/isaac-asimov

and:

https://www.notablebiographies.com/An-Ba/Asimov-Isaac.html

Right: Asimov circa 1980s (Goodreads.com)

I was an avid reader of science fiction during the time when Isaac Asimov’s novels on robots, the Foundation and the Galactic Empire were first being published. I was hooked with the first novel I read, Pebble in the Sky, and waited with anticipation until each new book became available in paperback.

You may remember that Asimov created the basic three laws of robotics:

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.

These laws were woven into the storyline of many of his books.

Unless you already have your favorite Asimov volumes on your bookshelf, I suggest that you visit the Internet Archive and the Open Library, which provide free access to many Asimov books as well as a vast range of other books and resources. You can set up a free account on the Internet Archive homepage here:

Log in and you’ll have access to many of Asimov’s books:

- The Foundation Trilogy is downloadable as audiobooks here: https://archive.org/details/IsaacAsimov-TheFoundationTrilogy

- The Open Library contains many of his books and other books about him, all of which you can borrow as e-books for two weeks. You can navigate to the Open Library from the Internet Archive home page or use the following direct link: https://openlibrary.org

In the Open Library, a search for “Isaac Asimov” will take you here:

https://openlibrary.org/authors/OL34221A/Isaac_Asimov

Now you’re almost ready to look for an available book in the Open Library and start reading. Note that you may be in a waitlist, because library rules for e-books limit the number of copies that can be checked out at any one time.

If you choose to read about robots, the Foundation and the Galactic Empire (books written over a 52 year period from 1940 to 1992), consider Asimov’s own recommendations regarding the chronological order of the stories, in terms of future history:

- The Complete Robot (1982). This is a collection of 31 robot short stories published between 1940 and 1976 and includes every story in Asimov’s earlier collection: I, Robot (1950).

- The Positronic Man (1992): A stand-alone robot novel set from the 22nd to 24th centuries, co-written with Robert Silverberg, based on Asimov’s 1976 novelette “The Bicentennial Man”

- Nemesis (1989): A standalone novel, set in the 23rd century in a star system about 2 light years from Earth, when interstellar travel was new

- Caves of Steel (1954). This is the 1st robot novel.

- The Naked Sun (1957). This is the 2nd robot novel.

- The Robots of Dawn (1983). This is the 3rd robot novel.

- Robots and Empire (1985). This is the 4th robot novel.

- The Currents of Space (1952). This is the 1st Empire novel.

- The Stars, Like Dust (1951). This is the 2nd Empire novel.

- Pebble in the Sky (1950). This was Asimov’s first novel. It is the 3rd Empire novel.

- Prelude to Foundation (1988): This is the 1st Foundation novel, actually a prequel.

- Forward the Foundation (1992): Published posthumously, this is the 2nd Foundation novel, and the 2nd prequel.

- Foundation (1951). This is the 3rd Foundation novel. It is a collection of four stories published between 1942 and 1944, plus an introductory section written in 1949.

- Foundation and Empire (1952). This is the 4th Foundation novel. It is made up of two stories originally published in 1945.

- Second Foundation (1953): This is the 5th Foundation novel. It is made up of two stories originally published in 1948 and 1949.

- Foundation’s Edge (1982): This is the 6th Empire novel.

- Foundation and Earth (1986): This is the 7th Empire novel.

- The End of Eternity (1955): A standalone novel, about Eternity, an organization “outside time” which aims to improve human happiness by altering history.

The above list is adapted and updated from the Author’s notes in Prelude to Foundation to account for books published after 1988.

I also recommend that you take the time to watch the following on YouTube:

- Isaac Asimov – The Last Question (28.06 minutes). This is one of Asimov’s best-known and most acclaimed short stories, published in 1951. Presented as a narration on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ojEq-tTjcc0

- Nightfall by Isaac Asimov – X Minus One (26:49 minutes): One of Asimov’s earliest short stories, published in 1941. This is a story about an inhabited planet with multiple suns. Presented as a narration on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aRJO4dYZ4NQ

- Interview of Isaac Asimov (23:18 minutes). This is a 1975 interview by Sy Bourgin on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xUz_KkibYAs

Search YouTube and you’ll find more Asimov audiobooks.

Thank you, Isaac Asimov, for inspiring generations of readers, and generations yet to come.