Peter Lobner

The Main Directorate of Deep-Sea Research, also known as GUGI and Military Unit 40056, is an organizational structure within the Russian Ministry of Defense that is separate from the Russian Navy. The Head of GUGI is Vice-Admiral Aleksei Burilichev, Hero of Russia.

Source. Adapted from Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation, http://eng.mil.ru/en/index.htm

Vice-Admiral Aleksei Burilichev at the commissioning of GUGI oceanographic research vessel Yantar. Source: http://eng.mil.ru/

GUGI is responsible for fielding specialized submarines, oceanographic research ships, undersea drones and autonomous vehicles, sensor systems, and other undersea systems. Today, GUGI operates the world’s largest fleet of covert manned deep-sea vessels. In mid-2018, that fleet consisted of eight very specialized nuclear-powered submarines.

There are six nuclear-powered, deep-diving, small submarines (“nuclear deep-sea stations”), each of which is capable of working at great depth (thousands of meters) for long periods of time. These subs are believed to have diver lockout facilities to deploy divers at shallower depths.

- One Project 1851 / 18510 Nelma (aka X-Ray) sub delivered in 1986; Length: 44 m (144.4 ft.); displacement about 529 tons submerged. This is the first and smallest of the Russian special operations nuclear-powered submarines.

- Two Project 18511 Halibut (aka Paltus) subs delivered between 1994 – 95; Length: 55 m (180.4 ft.); displacement about 730 tons submerged.

- Three Project 1910 Kashalot (aka Uniform) subs delivered between 1986 – 1991, but only two are operational in 2018; Length: 69 m (226.4 ft.); displacement about 1,580 tons submerged.

- One Project 09851 Losharik (aka NORSUB-5) sub delivered in about 2003; Length: 74 m (242.8 ft.); displacement about 2,100 tons submerged.

The trend clearly is toward larger, and certainly more capable deep diving special operations submarines. The larger subs have a crew complement of 25 – 35.

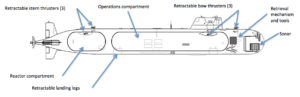

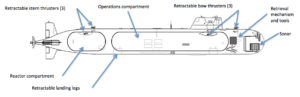

Kashalot notional cross-section diagram. Source: adapted from militaryrussia.ru

Kashalot notional diagram showing deployed positioning thrusters, landing legs and tools for working on the bottom. Source: http://nvs.rpf.ru/nvs/forum

Kashalot notional diagram showing deployed positioning thrusters, landing legs and tools for working on the bottom. Source: http://nvs.rpf.ru/nvs/forum

The Russian small special operations subs may have been created in response to the U.S. Navy’s NR-1 small, deep-diving nuclear-powered submarine, which entered service in 1969. NR-1 had a length of 45 meters (147.7 ft.) and a displacement of about 400 tons submerged, making it roughly comparable to the Project 1851 / 18510 Nelma . NR-1 was retired in 2008, leaving the U.S. with no counterpart to the Russian fleet of small, nuclear-powered special operations subs.

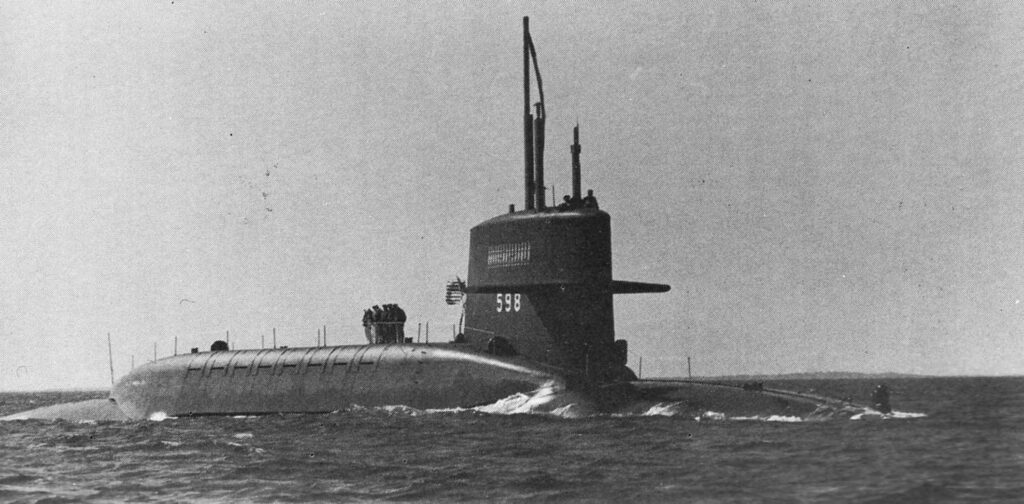

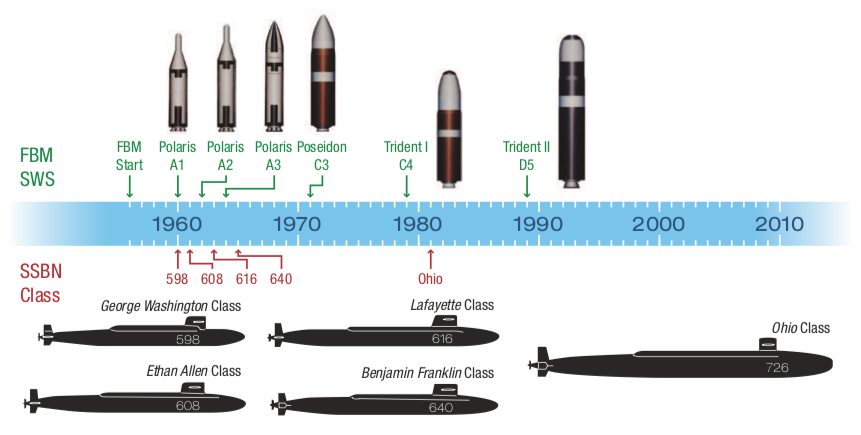

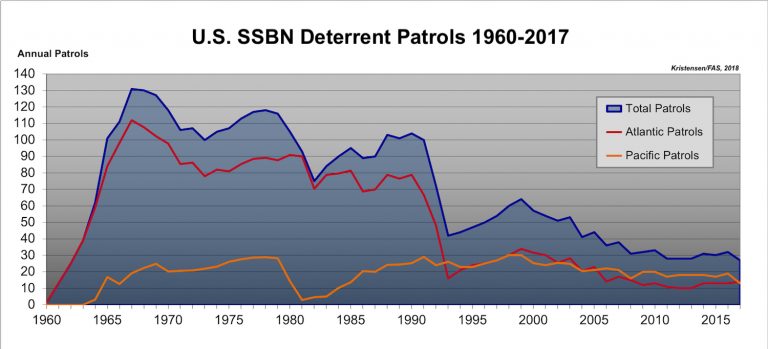

GUGI operates two nuclear-powered “motherships” (PLA carriers) that can transport one of the smaller nuclear deep-sea stations to a distant site and provide support throughout the mission. The current two motherships started life as Delta III and Delta IV strategic ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs). The original SSBN missile tubes were removed and the hulls were lengthened to create large midship special mission compartments with a docking facility on the bottom of the hull for one of the small, deep-diving submarines. These motherships probably have a test depth of about 250 to 300 meters (820 to 984 feet). They are believed to have diver lockout facilities for deploying divers.

General arrangement of a Russian mothership carrying a small special operations submarine. Source: http://gentleseas.blogspot.com/2015/08/russias-own-jimmy-carter-special-ops.html

General arrangement of a Russian mothership carrying a small special operations submarine. Source: http://gentleseas.blogspot.com/2015/08/russias-own-jimmy-carter-special-ops.html

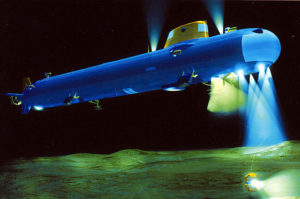

Delta-IV mothership carrying Losharik. Source: GlobalSecurity.org

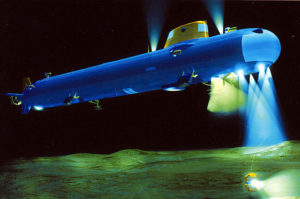

The motherships also are believed capable of deploying and retrieving a variety of autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), including the relatively large Harpsichord: Length: 6.5 m (21.3 ft.); Diameter 1 m (3.2 ft.); Weight: 3,700 kg (8,157 pounds).

Harpsichord-2R-PM. Source: http://vpk-news.ru/articles/30962

Harpsichord-2R-PM. Source: http://vpk-news.ru/articles/30962

The following graphic shows a mothership carrying a small special operations sub while operating with a Harpsichord AUV.

Source: https://russianmilitaryanalysis.wordpress.com/tag/9m730/

Source: https://russianmilitaryanalysis.wordpress.com/tag/9m730/

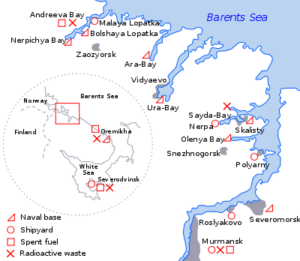

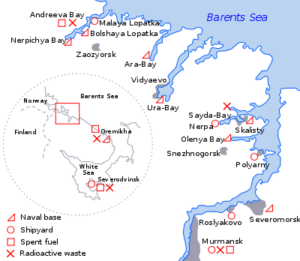

These nuclear submarines are operated by the 29th Special Submarine Squadron, which is based along with other GUGI vessels at Olenya Bay, in the Kola Peninsula on the coast of the Barents Sea.

Olenya Bay is near Murmansk. Source: Google Maps

Olenya Bay is near Murmansk. Source: Google Maps

Russian naval facilities near Murmansk. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org

Mothership BS-136 Orenburg at Oleyna Bay. Source: Source: http://www.air-defense.net/

Mothership BS-136 Orenburg at Oleyna Bay. Source: Source: http://www.air-defense.net/

The GUGI fleet provides deep ocean and Arctic operating capabilities that greatly exceed those of any other nation. Potential missions include:

- Conducting subsea surveys, mapping and sampling (i.e., to help validate Russia’s extended continental shelf claims in the Arctic; to map potential future targets such as seafloor cables)

- Placing and/or retrieving items on the sea floor (i.e., retrieving military hardware, placing subsea power sources, power distribution systems and sonar arrays)

- Maintaining military subsea equipment and systems

- Conducting covert surveillance

- Developing an operational capability to deploy the Poseidon strategic nuclear torpedo.

- In time of war, attacking the subsea infrastructure of other nations in the open ocean or in the Arctic (i.e., cutting subsea internet cables, power cables or oil / gas pipelines)

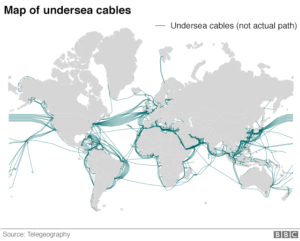

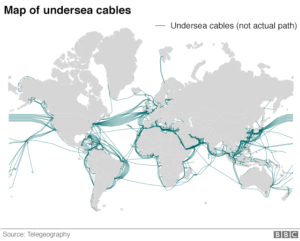

Analysts at the firm Policy Exchange reported that the world’s undersea cable network comprises about 213 independent cable systems and 545,018 miles (877,121 km) of fiber-optic cable. These undersea cable networks carry an estimated 97% of global communications and $10 trillion in daily financial transactions are transmitted by cables under the ocean.

Since about 2015, NATO has observed Russian vessels stepping up activities around undersea data cables in the North Atlantic. None are known to have been tapped or cut. Selective attacks on this cable infrastructure could electronically isolate and severely damage the economy of individual countries or regions. You’ll find a more detailed assessment on this matter in the 15 December 2017 BBC article, “Russia a ‘risk’ to undersea cables, Defence chief warns.”

http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-42362500

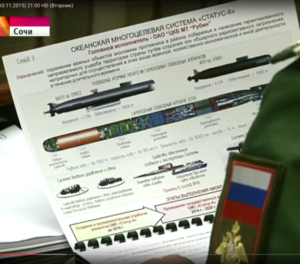

GUGI also is responsible for the development of the Poseidon (formerly known as Status-6 / Kanyon) strategic nuclear torpedo and the associated “carrier” submarines.

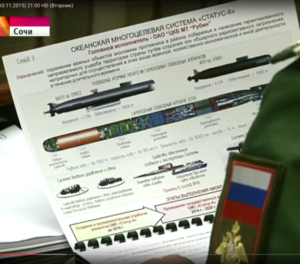

Poseidon, which was first revealed on Russian TV in November 2015, is a large, nuclear-powered, autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) that functionally is a giant, long-range torpedo.

The Russian TV “reveal” of the Oceanic Multipurpose System Status-6 November 2015. Source: https://russianmilitaryanalysis.wordpress.com/tag/9m730/

The Russian TV “reveal” of the Oceanic Multipurpose System Status-6 November 2015. Source: https://russianmilitaryanalysis.wordpress.com/tag/9m730/

It is capable of delivering a very large nuclear warhead (perhaps up to 100 MT) underwater to the immediate proximity of an enemy’s key economic and military facilities in coastal areas. It is a weapon of unprecedented destructive power and it is not subject to any existing nuclear arms limitation treaties. However, its development would give Russia leverage in future nuclear arms limitation talks.

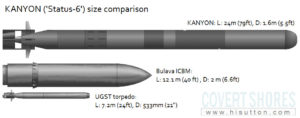

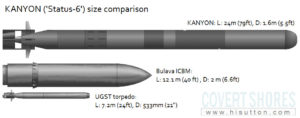

The immense physical size of the Poseidon strategic nuclear torpedo is evident in the size comparison chart below.

Source: http://www.hisutton.com/

Source: http://www.hisutton.com/

The Bulava is the Russian submarine launched ballistic missile (SLBM) carried on Russia’s modern Borei-class SSBNs. The UGST torpedo is representative of a typical torpedo launched from a 533 mm (21 inch) torpedo tube, which is found on the majority of submarines in the world. An experimental submarine, the B-90 Sarov, appears to be the current testbed for the Poseidon strategic torpedo. Russia is building other special submarines to carry several Poseidon strategic torpedoes. One is believed to be the giant, highly modified Oscar II submarine K-139 Belgorod, which also will serve as a mothership for a small, special operations nuclear sub. The other is the smaller Project 09851 submarine Khabarovsk, which appears to be purpose-built for carrying the Poseidon.

For more information on GUGI, Russian special operations submarines and other covert underwater projects, refer to the Covert Shores website created by naval analyst H. I. Sutton, which you’ll find at the following link:

http://www.hisutton.com/Analysis%20-%20Russian%20Status-6%20aka%20KANYON%20nuclear%20deterrence%20and%20Pr%2009851%20submarine.html

Kashalot notional diagram showing deployed positioning thrusters, landing legs and tools for working on the bottom. Source: http://nvs.rpf.ru/nvs/forum

Kashalot notional diagram showing deployed positioning thrusters, landing legs and tools for working on the bottom. Source: http://nvs.rpf.ru/nvs/forum General arrangement of a Russian mothership carrying a small special operations submarine. Source: http://gentleseas.blogspot.com/2015/08/russias-own-jimmy-carter-special-ops.html

General arrangement of a Russian mothership carrying a small special operations submarine. Source: http://gentleseas.blogspot.com/2015/08/russias-own-jimmy-carter-special-ops.html

Harpsichord-2R-PM. Source: http://vpk-news.ru/articles/30962

Harpsichord-2R-PM. Source: http://vpk-news.ru/articles/30962 Source: https://russianmilitaryanalysis.wordpress.com/tag/9m730/

Source: https://russianmilitaryanalysis.wordpress.com/tag/9m730/ Olenya Bay is near Murmansk. Source: Google Maps

Olenya Bay is near Murmansk. Source: Google Maps

Mothership BS-136 Orenburg at Oleyna Bay. Source: Source: http://www.air-defense.net/

Mothership BS-136 Orenburg at Oleyna Bay. Source: Source: http://www.air-defense.net/

The Russian TV “reveal” of the Oceanic Multipurpose System Status-6 November 2015. Source: https://russianmilitaryanalysis.wordpress.com/tag/9m730/

The Russian TV “reveal” of the Oceanic Multipurpose System Status-6 November 2015. Source: https://russianmilitaryanalysis.wordpress.com/tag/9m730/ Source: http://www.hisutton.com/

Source: http://www.hisutton.com/