Peter Lobner

1. Introduction

In June 2022, the Norwegian firm Ulstein (https://ulstein.com) announced their conceptual design of a Replenishment, Research and Rescue (3R) vessel named Thor that will be powered by a thorium molten salt reactor (MSR). This vessel can function as a seaborne mobile charging station for a small fleet of electrically-powered expedition / cruise ships that are designed to operate in environmentally sensitive areas such as the Arctic and Antarctic. Other environmentally sensitive areas include the West Norwegian Fjords, which are UNESCO World Heritage sites that will be closed in 2026 to all ships that are not zero-emission. In the future, similar regulations could be in place to protect other environmentally sensitive regions of the world, thereby reinforcing Ulstein’s business case behind Thor and its all-electric companion vessels.

Sif electrically-powered expedition / cruise vessel (right).

Source: Ulstein

2. The MSR-powered Thor charging station

Thor is a 149-meter (500-foot) long, zero-emission, nuclear-powered vessel that features Ulstein’s striking, backwards-sloping X-bow, which is claimed to result in a smoother ride, higher speed while using less energy, and less mechanical wear than a ship with a conventional bow.

For its R3 mission, Thor would be outfitted with work boats, cranes, a helicopter landing pad, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), unmanned surface vessels, firefighting equipment, rescue booms, a lecture hall and laboratories.

As a charging station, Thor would be sized to recharge four all-electric vessels simultaneously.

Thor also could serve as a floating power station, replacing diesel power barges in some developing countries or in some disaster areas while the local electric power infrastructure is being repaired.

Ulstein projects that an operational Thor vessel could be launched in “10 to 15 years.” However, the development and licensing of a marine MSR is on the critical path for that schedule.

3. The all-electric Sif expedition / cruise ship

Sif, named after the goddess who was Thor’s wife, is a design concept for a 100-meter (330-foot) long, all-electric, zero-emission expedition / cruise ship designed to operate with minimal impact in environmentally sensitive areas. The ship will be powered by a new generation of solid batteries that are expected to offer greater capacity and resistance to fire than lithium-ion batteries used commonly today. It will be periodically recharged at sea by Thor.

The ship can accommodate 80 passengers and 80 crew.

4. A marine MSR power plant

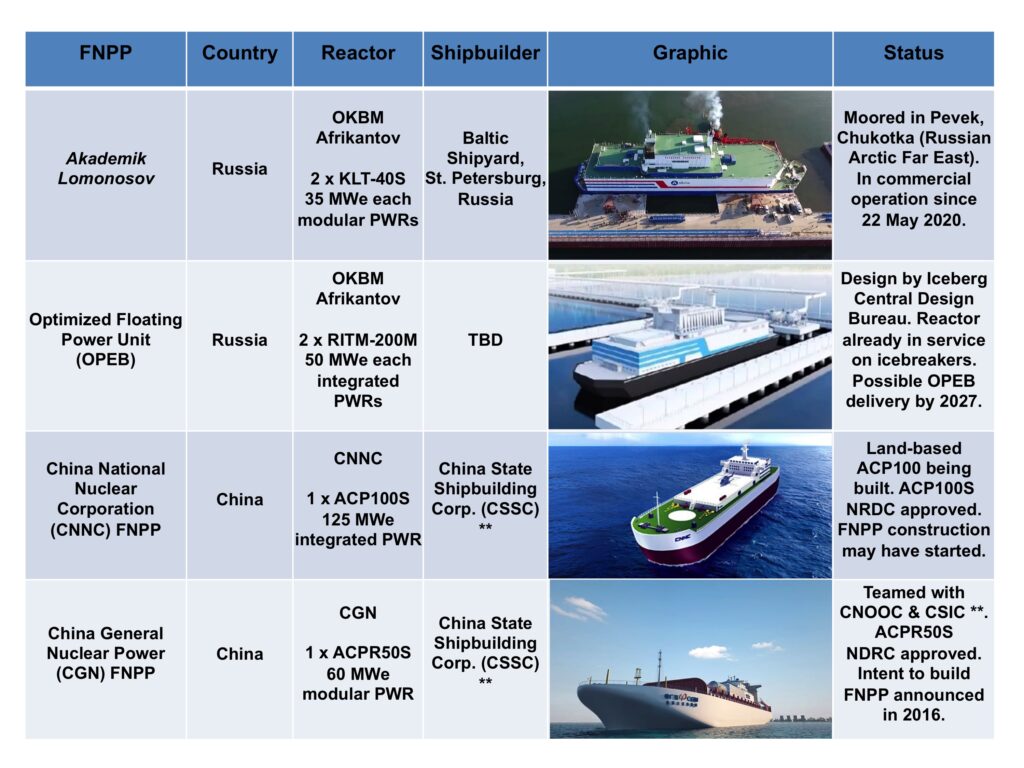

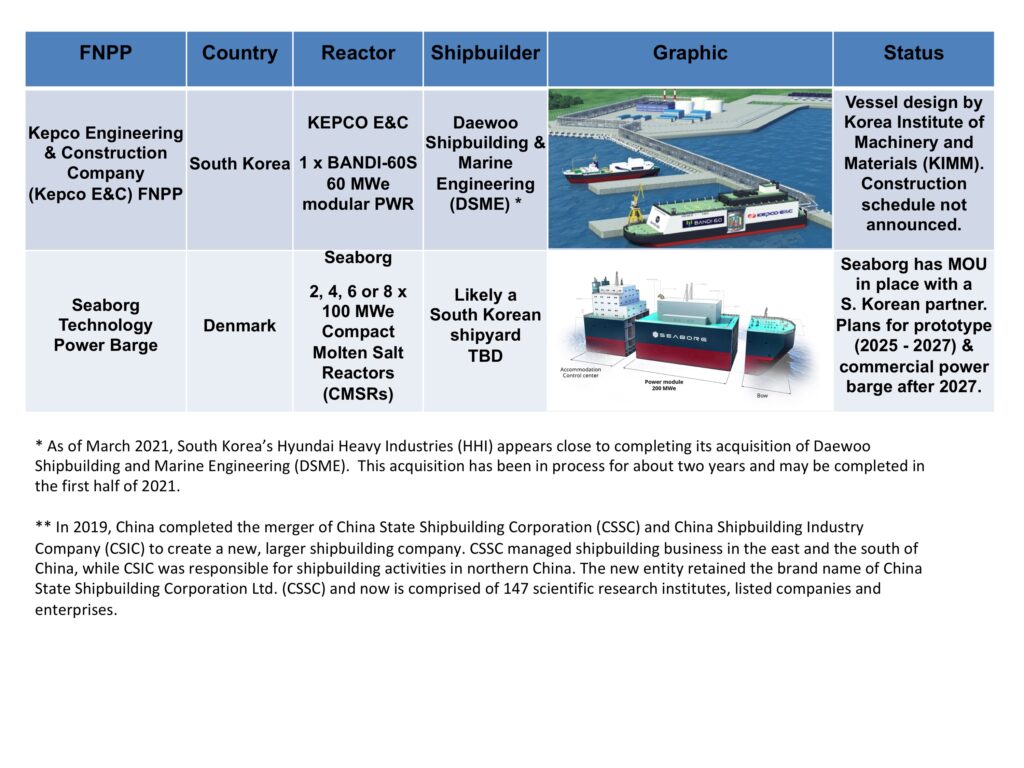

The pressurized water reactor (PWR) is the predominant marine nuclear power plant in use today, primarily in military vessels, but also in Russian icebreakers and a floating nuclear power plant in the Russian Arctic.

Ulstein reported that it has been exploring MSR technology because of its favorable operating and safety characteristics. For example, an MSR operates at atmospheric pressure (unlike a PWR) and passive features and systems maintain safety in an emergency. If the core overheats, the molten salt fuel/coolant mixture automatically drains out of the reactor and into a containment vessel where it safely solidifies and can be reused. You’ll find a good overview of MSR technology here: https://whatisnuclear.com/msr.html

While a few experimental MSRs have operated in the past, no MSR has been subject to a commercial nuclear licensing review, even for a land-based application. Ulstein favors a thorium-fueled MSR. The thorium-uranium-233 fuel cycle introduces additional technical and nuclear licensing uncertainties because of the lack of operational and nuclear regulatory precedents.

Several firms are developing MSR concepts. However, the combination of a marine MSR and a thorium fuel cycle remains elusive. Two uranium-fueled marine MSR design concepts are described below.

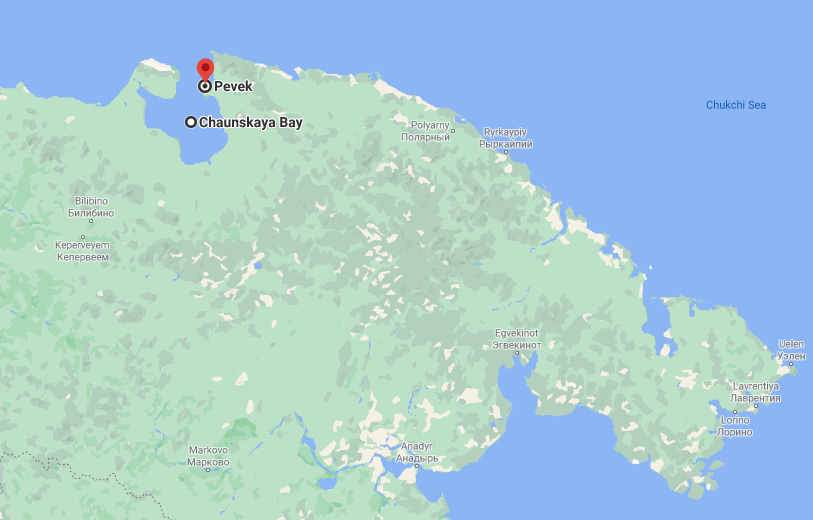

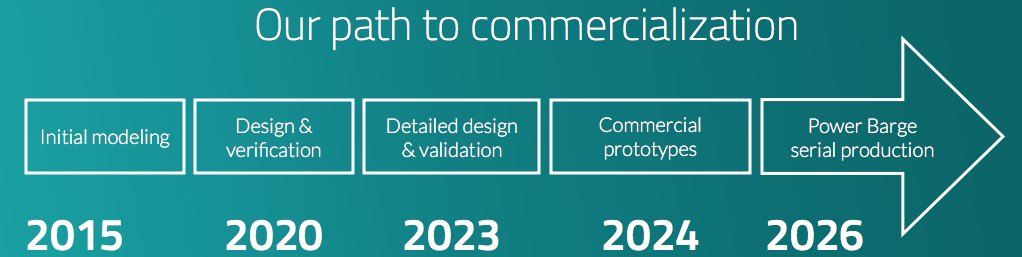

Seaborg Technologies

The Danish firm Seaborg Technologies (https://www.seaborg.com), founded in 2014, is developing a compact MSR (CMSR) with a rating of about 250 MWt / 100 MWe for use in power barges (floating nuclear power plants) of their own design (see my 16 May 2021 post). The thermal-spectrum CMSR uses uranium-235 fuel in a molten proprietary salt, with a separate sodium hydroxide (NaOH) moderator.

Seaborg’s development time line calls for a commercial CMSR prototype to be built in 2024, with commercial production of power barges beginning in 2026.

In April 2022, Seaborg and the Korean shipbuilding firm Samsung Heavy Industries signed a partnership agreement for manufacturing and selling turnkey CMSR power barges.

On 10 June 2022, Seaborg was selected by the European Innovation Council to receive a significant (potentially up to €17.5 million) innovation grant to help accelerate their work on the CMSR.

CORE-POWER and the Southern Company consortium

The UK firm CORE-POWER Ltd. (https://corepower.energy), founded in 2018, began with a concept for a compact uranium-235 fueled, molten chloride salt reactor named the m-MSR for marine applications. This modular, inherently safe, 15 MWe micro-reactor system was designed as a zero-carbon replacement power source for the fossil-fueled power plants in many existing commercial marine vessels. It also was intended for use as the original power source for new vessels, as proposed for the Earth 300 Eco-Yacht design concept unveiled by entrepreneur Aaron Olivera in April 2021 (see my 17 April 2021 post). The power output of a modular CORE-POWER m-MSR installation could be scaled to meet operational needs by adding reactor modules in compact arrangements suitable for shipboard installation.

could generate 90 MWe. Dump tank not shown. Source: CORE-POWER

In November 2020, CORE-POWER announced that it had joined an international consortium to develop MSRs. This team includes the US nuclear utility company Southern Company (https://www.southerncompany.com), US small modular reactor developer TerraPower (https://www.terrapower.com) and nuclear technology company Orano USA (https://www.orano.group/usa/en). In the consortium, TerraPower is responsible for the fast-spectrum Molten Chloride Fast Reactor (MCFR). CORE-POWER is responsible for maritime readiness and regulatory approvals.

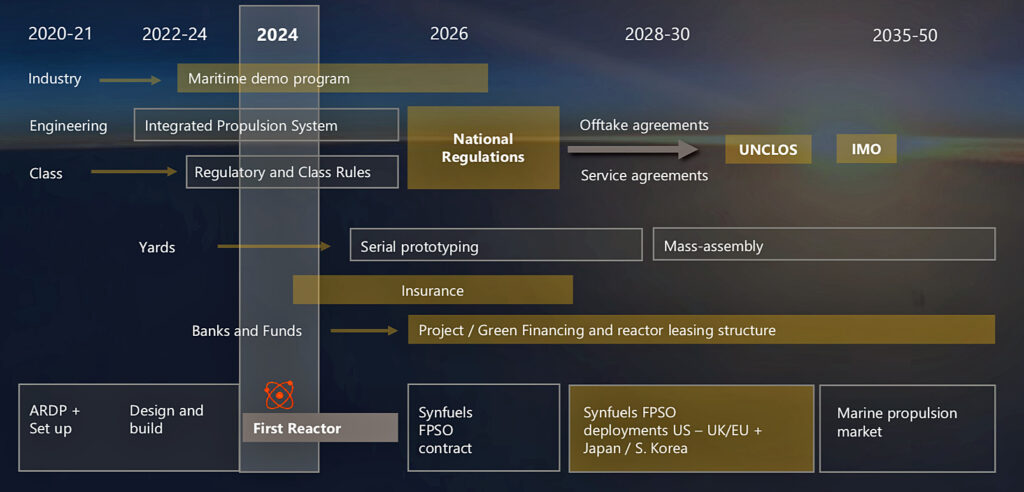

This consortium applied to the US Department of Energy (DOE) to participate in cost-share risk reduction awards under the Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program (ARDP), to develop a prototype MCFR as a proof-of-concept for a medium-scale commercial-grade reactor. In December 2020, the consortium was awarded $90.4 million, with the goal of demonstrating the first MCFR in 2024. DOE reported, “They expect to begin testing in a $20 million integrated effects test facility starting in 2022. The team has successfully scaled up the salt manufacturing process to enable immediate testing. Data generated from the test facility will be used to validate thermal hydraulics and safety analysis codes for licensing of the reactor.”In February 2021, CORE-POWER presented the MCFR development schedule in the following chart, which shows the MCFR becoming available for deployment in marine propulsion in about 2035. This is within the 10 to 15 year timescale projected by Ulstein for their first Thor vessel.

5. In conclusion

A seaborne nuclear-powered “charging station” supporting a small fleet of all-electric marine vessels provides a zero-carbon solution for operating in protected, environmentally sensitive areas that otherwise would be off limits to visitors. Ulstein’s concept for the MSR-powered Thor R3 vessel and the Sif companion vessel is a clever approach for implementing that strategy.

It appears that a uranium-fueled marine MSR could be commercially available in the 10 to 15 year time frame Ulstein projects for deploying Thor and Sif. The technical and nuclear regulatory uncertainties associated with a thorium-fueled marine MSR will require a considerably longer time frame.

6. For additional information

Ulstein Thor & Sif

- “Ship design concept from Ulstein can solve zero-emission challenge,” Ulstein press release, 26 April 2022: https://ulstein.com/news/ulstein-thor-zero-emission-concept

- “Nuclear vessel could be floating charging station for electric cruise ships,” World Nuclear News, 29 April 2022: https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Ulstein-touts-nuclear-concept-for-decarbonising-cr

- “Ulstein reveals thorium-powered ship concept to support ecocruising,” New Atlas, 3 May 2022: https://newatlas.com/marine/ulstein-thorium-powered-ship-concept-ecocruising/

- Jacopo Prisco, “Nuclear power could be the future of expedition cruises,” CNN travel, 3 June 2022: https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/ulstein-thor-nuclear-powered-ship/index.html

Video

- “’Thor’ – a Thorium Molten Salt Reactor ship design by Ulstein for Replenishment, Research and Rescue,” (2:16 min), Ulstein, 26 April 2022: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IBRVb0-0kAw

Seaborg CMSR

- Peter Lobner, “Denmark’s Seaborg Technologies CMSR Power Barge Concept,” The Lyncean Group of San Diego, 15 May 2021: https://secureservercdn.net/198.71.233.28/gkz.aeb.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Denmark-Seaborg-CMSR-Power-Barge-converted.pdf

- Peter Mateusz, “Molten salt revisited: the CMSR,” Nuclear Engineering International, 24 January 2022: https://www.neimagazine.com/features/featuremolten-salt-revisited-the-cmsr-9423379/

- Seaborg Partners With Samsung,” Seaborg press release, 7 April 2022: https://www.seaborg.com/press-release-samsung

- “Samsung, Seaborg partnership on floating nuclear reactors,” World Nuclear News, 8 April 2022: https://world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Samsung,-Seaborg-partnership-on-floating-nuclear-r

CORE-POWER m-MSR

- “Core Power joins team to develop MSR technology to power ships,” Ship Technology, 3 November 2020: https://www.ship-technology.com/news/core-power-msr-technology-ships/

- “Core Power thinks nuclear will make waves in commercial shipping,” Nuclear Newswire, American Nuclear Society, 5 November 2020: https://www.ans.org/news/article-2348/core-power-thinks-nuclear-will-make-waves-in-commercial-shipping/

- “Zero-emission energy revolution for ocean transportation,” Core-Power (UK) Ltd., NAMEPA briefing, February 2021: https://namepa.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/2021.CORE-POWER-K37-EN-NAMEPA.pdf

- Peter Lobner, “The Earth 300 Eco-Yacht Could Serve as a Prototype for De-carbonizing the World’s Commercial Marine Transportation Fleets,” The Lyncean Group of San Diego, 17 April 2021: https://lynceans.org/all-posts/the-earth-300-eco-yacht-could-serve-as-a-prototype-for-de-carbonizing-the-worlds-commercial-marine-transportation-fleets/

- “Southern Company and TerraPower Prep for Testing on Molten Salt Reactor,” DOE Office of Nuclear Energy, 29 November 2021: https://www.energy.gov/ne/articles/southern-company-and-terrapower-prep-testing-molten-salt-reactor