Peter Lobner

1. Background:

We’re all familiar with scenes of the Apollo astronauts bounding across the lunar surface in the low gravity on the Moon, where gravity (g) is 0.17 of the gravity on the Earth’s surface. Driving the Apollo lunar rover kicked up some dust, but otherwise proved to be a practical means of transportation on the Moon’s surface. While the Moon’s gravity is low relative to Earth, techniques for achieving lunar orbit have been demonstrated by many spacecraft, many soft landings have been made, locomotion on the Moon’s surface with wheeled vehicles has worked well, and there is no risk of flying off into space by accidentally exceeding the Moon’s escape velocity.

There are many small bodies in the Solar System (i.e., dwarf planets, asteroids, comets) where gravity is so low that it creates unique problems for visiting spacecraft and future astronauts: For example:

- Spacecraft require efficient propulsion systems and precise navigation along complex trajectories to rendezvous with the small body and then move into a station-keeping position or establish a stable orbit around the body.

- Landers require precise navigation to avoid hazards on the surface of the body (i.e., craters, boulders, steep slopes), land gently in a specific safe area, and not rebound back into space after touching down.

- Rovers require a locomotion system that is adapted to the specific terrain and microgravity conditions of the body and allows the rover vehicle to move across the surface of the body without risk of being launched back into space by reaction forces.

- Many asteroids and comets are irregularly shaped bodies, so the surface gravity vector will vary significantly depending on where you are relative to the center of mass of the body.

You will find a long list of known objects in the Solar System, including many with diameters less than 1 km (0.62 mile), at the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Solar_System_objects_by_size

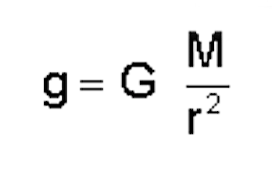

You can determine the gravity on the surface of a body in the Solar System using the following equation:

where (using metric):

g = acceleration due to gravity on the surface of the body (m/sec2)

G = universal gravitational constant = 6.672 x 10-11 m3/kg/sec2

M = mass of the body (kg)

r = radius of the body (which is assumed to be spherical) (m)

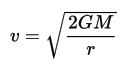

You can determine the escape velocity from a body using the following equation:

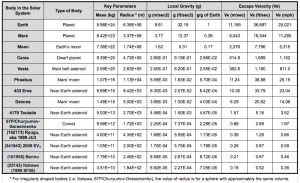

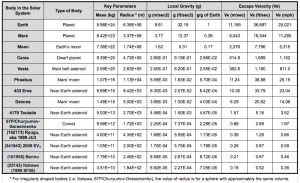

Applying these equations to the Earth and several smaller bodies in in the Solar System yields the following results:

Note how weak the gravity is on the small bodies in this table. These are very different conditions than on the surface of the Moon or Mars where the low gravity still allows relatively conventional locomotion.

As noted in my 31 December 2015 post, the “U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act,” which was signed into law on 25 November 2015, opens the way for U.S. commercial exploitation of space, including commercial missions to asteroids and comets. Let’s take a look at missions to these microgravity worlds and some of the unique issues associated with visiting a microgravity world.

2. Recent and Current Missions to Asteroids and Comets

There have been several spacecraft that have made a successful rendezvous with one or more small bodies in the Solar System. Several have been fly-by missions. Four spacecraft have flown in close formation with or entered orbit around low-gravity bodies. Three of these missions included landing on (or at least touching) the body, and one returned very small samples to Earth. These missions are:

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) NEAR-Shoemaker

- Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s (JAXA) Hayabusa

- European Space Agency’s (ESA) Rosetta

- NASA’s Dawn

In addition, China’s Chang’e 2 mission demonstrated its ability to navigate to an asteroid intercept after completing its primary mission in lunar orbit. JAXA’s Hayabusa 2 mission currently is enroute to asteroid rendezvous.

Following is a short synopsis of each of these missions.

NASA’s NEAR-Shoemaker Mission (1996 – 2001): This mission was launched 17 February 1996 and on 27 June 1997 flew by the asteroid 253 Mathilde at a distance of about 1,200 km (746 miles). On 14 February 2000, the spacecraft reached its destination and entered a near-circular orbit around the asteroid 433 Eros, which is about the size of Manhattan. After completing its survey of Eros, the NEAR spacecraft was maneuvered close to the surface and it touched down on 12 February 2001, after a four-hour descent, during which it transmitted 69 close-up images of the surface. Transmissions continued for a short time after landing. NEAR-Shoemaker was the first man-made object to soft-land on an asteroid.

Asteroid EROS. Source: NASA/JPL/JHUAPL

Asteroid EROS. Source: NASA/JPL/JHUAPL

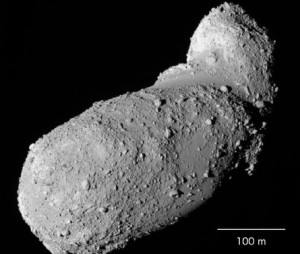

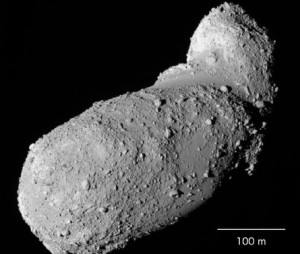

JAXA’s Hayabusa Mission (2003 – 2010): The Hayabusa spacecraft was launched in May 2003. This solar-powered, ion-driven spacecraft rendezvoused with near-Earth asteroid 25143 Itokawa in mid-September 2005.

Asteroid Itokawa. Source: JAXA

Asteroid Itokawa. Source: JAXA

Hayabusa carried the solar-powered MINERVA (Micro/Nano Experimental Robot Vehicle for Asteroid) mini-lander, which was designed to be released close to the asteroid, land softly, and move across the surface using an internal flywheel and braking system to generate the momentum needed to hop in microgravity. However, MINERVA was not captured by the asteroid’s gravity after being released and was lost in deep space.

In November 2005, Hayabusa moved in from its station-keeping position and briefly touched the asteroid to collect surface samples in the form of tiny grains of asteroid material.

Hayabusa in position to obtain samples. Source: JAXA

Hayabusa in position to obtain samples. Source: JAXA

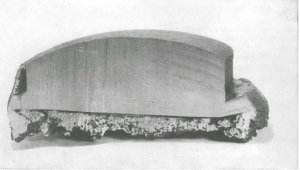

The spacecraft then backed off and navigated back to Earth using its failing ion thrusters. Hayabusa returned to Earth on 13 June 2010 and the sample-return capsule, with about 1,500 grains of asteroid material, was recovered after landing in the Woomera Test Range in the western Australian desert.

You’ll find a JAXA mission summary briefing at the following link:

https://www.nasa.gov/pdf/474206main_Kuninaka_HayabusaStatus_ExploreNOW.pdf

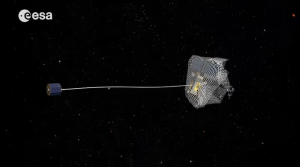

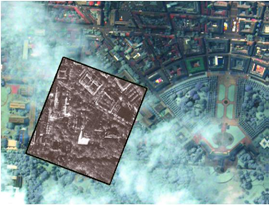

ESA’s Rosetta Mission (2004 – present): The Rosetta spacecraft was launched in March 2004 and in August 2014 rendezvoused with and achieved orbit around irregularly shaped comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. This comet orbits the Sun outside of Earth’s orbit, between 1.24 and 5.68 AU (astronomical units; 1 AU = average distance from Earth’s orbit to the Sun). The size of 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko is compared to downtown Los Angeles in the following figure.

Source: ESA

Source: ESA

Currently, Rosetta remains in orbit around this comet. The lander, Philae, is on the surface after a dramatic rebounding landing on 12 November 2014. Anchoring devices failed to secure Philae after its initial touchdown. The lander bounced twice and finally came to rest in an unfavorable position after contacting the surface a third time, about two hours after the initial touchdown. Philae was the first vehicle to land on a comet and it briefly transmitted data back from the surface of the comet in November 2014 and again in June – July 2015.

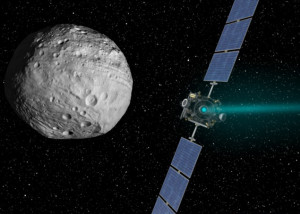

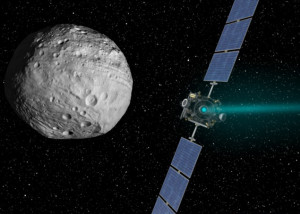

NASA’s Dawn Mission (2007 – present): Dawn was launched on 27 September 2007 and used its ion engine to fly a complex flight path to a 2009 gravitational assist flyby of Mars and then a rendezvous with the large asteroid Vesta (2011 – 2012) in the main asteroid belt.

Dawn approaches Vesta. Source: NASA / JPL Caltech

Dawn approaches Vesta. Source: NASA / JPL Caltech

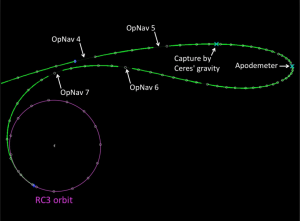

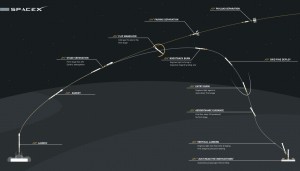

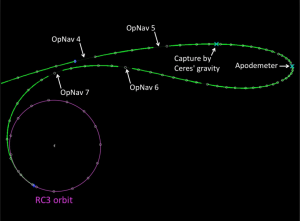

Dawn spent 14 months in orbit surveying Vesta before departing to its next destination, the dwarf planet Ceres, which also is in the main asteroid belt. On 6 March 2015 Dawn was captured by Ceres’ gravity and entered its initial orbit following the complex trajectory shown in the following diagram.

Dawn captured by Ceres gravity. Source: NASA / JPL Caltech

Dawn captured by Ceres gravity. Source: NASA / JPL Caltech

Dawn is continuing its mapping mission in a circular orbit at an altitude of 385 km (240 miles), circling Ceres every 5.4 hours at an orbital velocity of about 983 kph (611 mph). The Dawn mission does not include a lander.

See my 20 March 2015 and 13 Sep 2015 posts for more information on the Dawn mission.

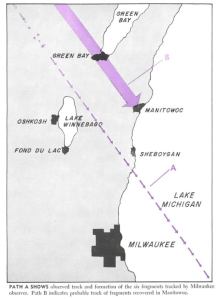

CNSA’s Chang’e 2 extended mission (2010 – present): The China National Space Agency’s (CNSA) Chang’e 2 spacecraft was launched in October 2010 and placed into a 100 km lunar orbit with the primary objective of mapping the lunar surface. After completing this objective in 2011, Chang’e 2 navigated to the Earth-Sun L2 Lagrange point, which is a million miles from Earth in the opposite direction of the Sun. In April 2012, Chang’e 2 departed L2 for an extended mission to asteroid 4179 Toutatis, which it flew by in December 2012.

Asteroid Toutatis. Source: CHSA

Asteroid Toutatis. Source: CHSA

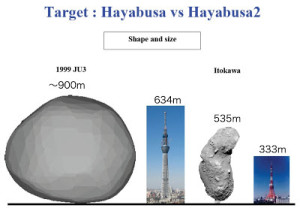

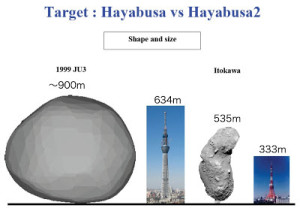

JAXA’s Hayabusa 2 Mission (2014 – 2020): The JAXA Hayabusa 2 spacecraft was launched on 3 December 2014. This ion-propelled spacecraft is very similar to the first Hayabusa spacecraft. Its planned arrival date at the target asteroid, 1999 JU3 (Ryugu), is in mid-2018. As you can see in the following diagram, 1999 JU3 is a substantially larger asteroid than Itokawa.

Source: JAXA

Source: JAXA

The spacecraft will spend about a year mapping the asteroid using Near Infrared Spectrometer (NIRS3) and Thermal Infrared Imager (TIR) instruments.

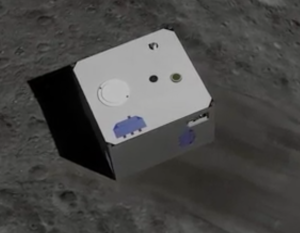

Hayabusa 2 includes three solar-powered MINERVA-II mini-landers and one battery-powered MASCOT (Mobile Asteroid Surface Scout) small lander. All landers will be deployed to the asteroid surface from an altitude of about 100 meters (328 feet) so they can be captured by the asteroid’s very weak gravity. The 1.6 – 2.5 kg (3.5 – 5.5 pounds) MINERVA-II landers will deliver imagery and temperature measurements. The 10 kg (22 pound) MASCOT will make measurements of surface composition and properties using a camera, magnetometer, radiometer, and infrared microscope. All landers are expected to make several hops to take measurements at different locations on the asteroid’s surface.

Three MINERVA mini-landers. Source: JAXA

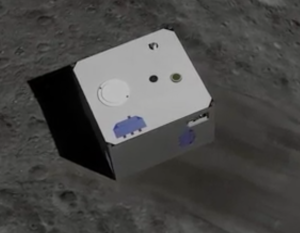

MASCOT small lander. Source: JAXA

MASCOT small lander. Source: JAXA

For sample collection, Hayabusa 2 will descend to the surface to capture samples of the surface material. A device called a Small Carry-on Impactor (SCI) will be deployed and should impact the surface at about 2 km/sec, creating a small crater to expose material beneath the asteroid’s surface. Hayabusa 2 will attempt to gather a sample of the exposed material. More information about SCI is available at the following link:

http://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2013/pdf/1904.pdf

At the end of 2019, Hayabusa 2 is scheduled to depart asteroid 1999 JU3 (Ryugu) and return to Earth in 2020 with the collected samples. You will find more information on the Hayabusa 2 mission at the JAXA website at the following links:

http://global.jaxa.jp/projects/sat/hayabusa2/

and,

http://www.lpi.usra.edu/sbag/meetings/jan2013/presentations/sbag8_presentations/TUES_0900_Hayabusa-2.pdf

3. Future Missions:

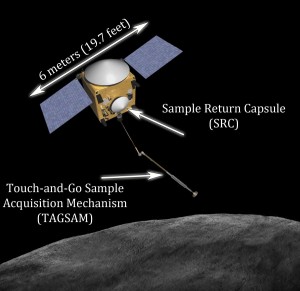

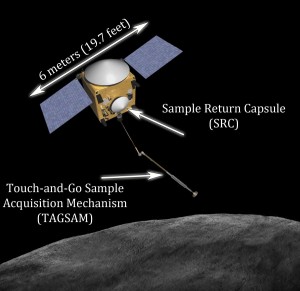

NASA OSIRIS-REx: This NASA’s mission is expected to launch in September 2016, travel to the near-Earth asteroid 101955 Bennu, map the surface, harvest a sample of surface material, and return the samples to Earth for study. After arriving at Bennu in 2018, the solar-powered OSIRIS-Rex spacecraft will map the asteroid surface from a station-keeping distance of about 5 km (3.1 miles) using two primary mapping instruments: the OVIRS Visible and Infrared Spectrometer and the OTRS Thermal Emission Spectrometer. Together, these instruments are expected to develop a comprehensive map of Bennu’s mineralogical and molecular components and enable mission planners to target the specific site(s) to be sampled. In 2019, a robotic arm on OSIRIS-REx will collect surface samples during one or more very close approaches, without landing. These samples (60 grams minimum) will be loaded into a small capsule that is scheduled to return to Earth in 2023.

OSIRIS-REx spacecraft. Source: NASA / ASU

OSIRIS-REx spacecraft. Source: NASA / ASU

For more information on OSIRIS-REx, visit the NASA website at the following link:

http://sservi.nasa.gov/articles/nasas-asteroid-sample-return-mission-moves-into-development/

and the ASU website at the following link:

http://www.asteroidmission.org/objectives/

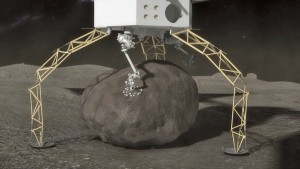

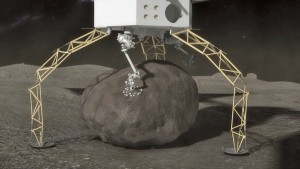

NASA Asteroid Redirect Mission (ARM): This mission will involve rendezvousing with a near-Earth asteroid, mapping the surface for about a year, and locating a suitable bolder to be captured [maximum diameter about 4 meters (13.1 feet)]. The ARM spacecraft will land and capture the intended bolder, lift off and deliver the bolder into a stable lunar orbit during the first half of the next decade. The current reference target is known as asteroid 2008 EV5.

ARM lander gripping a bolder on an asteroid. Source: NASA

ARM lander gripping a bolder on an asteroid. Source: NASA

You can find more information on the NASA Asteroid Redirect Mission at the following links:

https://www.nasa.gov/content/what-is-nasa-s-asteroid-redirect-mission

and

https://www.nasa.gov/pdf/756122main_Asteroid%20Redirect%20Mission%20Reference%20Concept%20Description.pdf

4. Locomotion in Microgravity

OK, you’ve landed on a small asteroid, your spacecraft has anchored itself to the surface and now you want to go out and explore the surface. If this is asteroid 2008 EV5, the local gravity is about 1.79 E-05 that of Earth (less than 2/100,000 the gravity of Earth) and the escape velocity is about 0.6 mph (1 kph). Just how are you going to move about on the surface and not launch yourself on an escape trajectory into deep space?

There is a good article on the problems of locomotion in microgravity in a 7 March 2015 article entitled, “A Lightness of Being,” in the Economist magazine. You can find this article on the Economist website at the following link:

http://www.economist.com/news/technology-quarterly/21645508-space-vehicles-can-operate-ultra-low-gravity-asteroids-and-comets-are

In this article, it is noted that:

“Wheeled and tracked rovers could probably be made to work in gravity as low as a hundredth of that on Earth……But in the far weaker microgravity of small bodies like asteroids and comets, they would fail to get a grip in fine regolith. Wheels also might hover above the ground, spinning hopelessly and using up power. So an entirely different system of locomotion is needed for rovers operating in a microgravity.”

Novel concepts for locomotion in microgravity include:

- Hoppers / tumblers

- Structurally compliant rollers

- Grippers

Hoppers / tumblers: Hoppers are designed to move across a surface using a moving internal mass that can be controlled to transfer momentum to the body of the rover to cause it to tumble or to generate a more dramatic hop, which is a short ballistic trajectory in microgravity. The magnitude of the hop must be controlled so the lander does not exceed escape velocity during a hop. JAXA’s MINERVA-II and MASCOT asteroid landers both are hoppers.

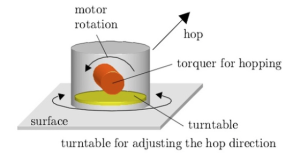

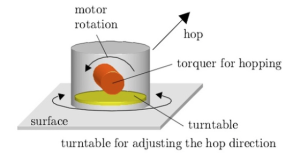

JAXA described the MINERVA-II hopping mechanism as follows:

“MINERVA can hop from one location to another using two DC motors – the first serving as a torquer, rotating an internal mass that leads to a resulting force, sufficient to make the rover hop for several meters. The second motor rotates the table on which the torquer is placed in order to control the direction of the hop. The rover reaches a top speed of 9 centimeters per second, allowing it to hop a considerable distance.”

MINERVA torque & turntable. Source: JAXA

MINERVA torque & turntable. Source: JAXA

The MASCOT hopper operates on a different principle:

“With a mass of not even half a gram in the gravitational field of the asteroid, the (MASCOT) lander can easily withstand its initial contact with the surface and several bounces that are expected upon landing. It also means that only small forces are needed to move the lander from point to point. MASCOT’s Mobility System essentially consists of an off-centered mass installed on an eccentric arm that moves that mass to generate momentum that is sufficient to either rotate the lander to face the surface with its instruments or initiate a hop of up to 70 meters to get to the next sampling site.”

MASCOT mobility mechanism. Source: JAXA

MASCOT mobility mechanism. Source: JAXA

You will find a good animation of MASCOT and its Mobility System at the following link:

http://www.dlr.de/dlr/en/desktopdefault.aspx/tabid-10081/151_read-18664/#/gallery/23722

NASA is examining a class of microgravity rovers called “hedgehogs” that are designed to hop and tumble on microgravity surfaces by spinning and braking a set of three internal flywheels. Cushions or spikes at the corners of the cubic body of a hedgehog protect the body from the terrain and act as feet while hopping and tumbling.

NASA Hedgehog prototype. Source: NASA

NASA Hedgehog prototype. Source: NASA

Read more on the NASA hedgehog rovers at the following link:

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=4712

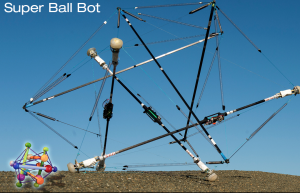

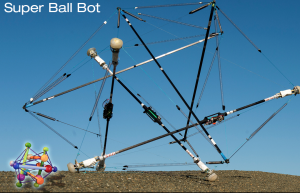

Structurally compliant rollers: One means of “rolling” across a microgravity surface is with a deformable structure that allows the location of the center of mass to be controlled in a way that causes the rover to tip over in the desired direction of motion. NASA is exploring the use of a class of rolling rovers called Super Ball Bots, which are terrestrial rovers based on a R. Buckminster Fuller’s tensegrity toy. NASA explains:

“The Super Ball Bot has a sphere-like matrix of cables and joints that could withstand being dropped from a spacecraft high above a planetary surface and hit the ground with a bounce. Once on the planet, the joints could adjust to roll the bot in any direction while housing a data collecting device within its core.”

Source: http://www.nasa.gov/content/super-ball-bot

Source: http://www.nasa.gov/content/super-ball-bot

You’ll find a detailed description of the principles behind tensegrity (tensional integrity) in a 1961 R. Buckminster Fuller paper at the following link:

http://www.rwgrayprojects.com/rbfnotes/fpapers/tensegrity/tenseg01.html

Grippers: Without having a grip on a microgravity body, a rover cannot use sampling tools that generate a reaction force on the rover (i.e., drills, grinders, chippers). For such operations to be successful a rover needs an anchoring system to secure the rover and transfer the reaction loads into the microgravity body.

An approach being developed by Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) involves articulated feet with microspine grippers that have a large number of small claws that can grip irregular rocky surfaces.

Microspine gripper. Source: NASA / JPL

Microspine gripper. Source: NASA / JPL

Such a gripper could be used to hold a rover in place during mechanical sampling activities or to allow a rover to climb across an irregular surface like a spider. See more about the operation of the NASA / JPL microspine gripper at the following link:

https://www-robotics.jpl.nasa.gov/tasks/taskVideo.cfm?TaskID=206&tdaID=700015&Video=147

5. Conclusions

Missions to small bodies in our Solar System are very complex undertakings that require very advanced technologies in many areas, including: propulsion, navigation, autonomous controls, remote sensing, and locomotion in microgravity. The ambitious current and planned future missions will greatly expand our knowledge of these small bodies and the engineering required to operate spacecraft in their vicinity and on their surface.

While commercial exploitation of dwarf planets, asteroids and comets still may sound like science fiction, the technical foundation for such activities is being developed now. It’s hard to guess how much progress will be made in the next decades. However, I’m convinced that the “U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act,” will encourage commercial investments in space exploration and exploitation and lead to much greater progress than if we depended on NASA alone.

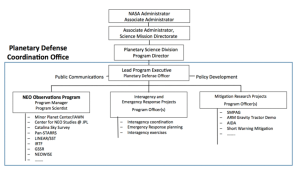

The technologies being developed also may lead, in the long term, to effective techniques for redirecting an asteroid or comet that poses a threat to Earth. Such a development would give our Planetary Defense Officer (see my 21 January 2016 post) an actual tool for defending the planet.

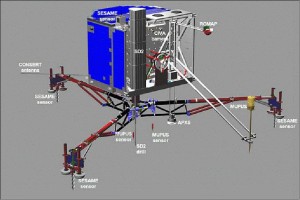

Main components of the Philae lander. Source: Philae team

Main components of the Philae lander. Source: Philae team Philae as it was intended to look after landing. Source: MEDIALAB/AFP/Getty Images

Philae as it was intended to look after landing. Source: MEDIALAB/AFP/Getty Images View from Philae’s actual landing site. Source: ESA

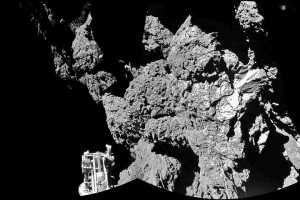

View from Philae’s actual landing site. Source: ESA Philae’s final resting place on comet 67P. Source: ESA

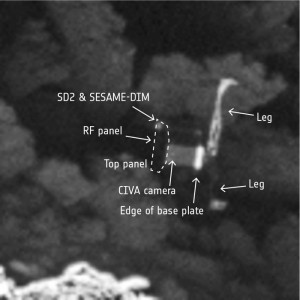

Philae’s final resting place on comet 67P. Source: ESA Annotated Philae photo. Source: ESA

Annotated Philae photo. Source: ESA